Leisure • Psychotherapy

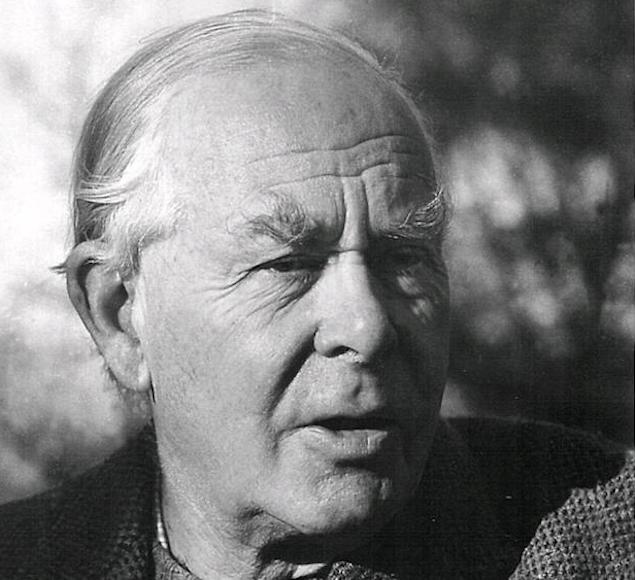

John Bowlby

Among our deepest and seemingly most natural aspirations is the longing to form stable, satisfying relationships: to thrive in partnerships that are good for both people. It doesn’t seem much to ask. A lot of people are looking for roughly the same thing. But the painful fact is that very large numbers of relationships have one difficult episode after another, or seemingly intractable miserable conflicts running through them; relationships feel like a struggle, rather than a support. It’s one of the biggest questions: why is it so hard for us to have the happy, constructive relationships we all want?

The huge – and not yet fully digested – insight of psychoanalysis is that the challenges of relationships do not start over dinner in an interesting restaurant or a college bar. They start, in fact, when we are children. There is no more important period of our lives than childhood; a good childhood is the bedrock of a happy life and a bad one just about dooms us to enduring misery. It was the contribution of the great psychoanalyst John Bowlby to trace the tensions and conflicts we have with our partners back to our early experience of maternal care.

His ideas are sound in part because he drew so deeply and honestly on his own experiences in order to formulate them. Born in 1907, Edward John Mostyn Bowlby had a quintessentially upper class British childhood. His father was a famous and highly successful doctor, with a knighthood and royal connections. Young Bowlby hardly saw his parents and was looked after by a lovely nanny, Minnie. But Minnie was an employee, and when John was four, she was sent away. His parents weren’t being deliberately callous. They (like pretty much everyone else at the time) didn’t realise how wounding her departure could be. At seven, Bowlby went off – in line with the conventions of his class – to boarding school, to a realm from which maternal warmth was rigorously excluded.

Bowlby was a brilliant medical student and an imaginative researcher. In 1952 he made a film, A Two-Year-Old Goes to Hospital, which showed the suffering a child went through when they were institutionally separated from their parents. In the wards mothers were not allowed to hold their sick children, for instance, for fear of spreading germs. Visiting times were punitively restricted.

When he was a consultant to the World Health Organisation in the early 1950s, Bowlby wrote a report, ‘Maternal Care and Mental Health’. He attacked prevalent assumptions (including those vigorously maintained by his own mother), arguing that kindness does not smother and spoil children. And he asserted the importance to both child and mother of developing an intimate and enjoyable relationship. This initiated a wave of reform: the visitation rules of many health institutions were reformed – a dry, bureaucratic move that ended countless afternoons of quiet sorrow and evenings of solitary anguish.

Bowlby poignantly invokes loving care that a little boy needs: ‘all the cuddling and playing, the intimacies of suckling by which a child learns the comfort of his mother’s body, the rituals of washing and dressing by which through her pride and tenderness towards his little limbs he learns the values of his own…’ Such experiences teach a basic trust: that difficulties can be managed; that slip-ups are only that and can be put right, that we are naturally entitled to be treated warmly and considerately, without having to do anything to earn this and without having to make special pleas or demands. ‘’It is as if maternal care were as necessary for the proper development of personality as vitamin D for the proper development of bones.’

The ideal parent is there when the child needs it. They are good at actually listening to what the child is saying. They help the child work out for itself what it is feeling. The ideal parent is not anxiously hanging around trying to micromanage everything. The ideal parent makes it feel that problems, difficulties and dangers don’t always have to be avoided: they can be coped with, solved or skillfully overcome. Such a parent makes the child secure. Not just that the child feels secure at particular moments but that they take this security with them into the tasks of life: they become secure people, so that they are less urgently in need of external validation, less devastated by failure, less in need of markers of status to reassure themselves of their own worth – because they carry within them a stable, reasonable, secure sense of who they are.

But the fact is that we often don’t quite get the maternal care we need. Parents – without meaning to let anyone down – go wrong in endless ways. They are inconsistent: at one point they are hugely available, happy to play and do things; then suddenly they are sternly busy and remote. Or they might be sweet and tender – but equally they might be angry or grumpy. They are around, then they disappear. They might be busy almost all the time, or very much preoccupied by work or social life. Their own fears, anxieties or troubles may keep them from providing the wise, generous attention the child needs.

In a book published in 1959 called Separation Anxiety Bowlby looks at what happens when there isn’t enough maternal care. He described the behaviour of children he had observed who had been separated from their parents. They went through three stages: protest, despair and detachment. The first phase began as soon as the parent left, and it would last between a few hours and a week. Protesting children would cry, roll around and react to any movement as the possibility of their mother returning.

If something like this is frequently experienced, then the child craves the attention, love and interest of the parents but feels that anything good may disappear at any moment. They look for a lot of reassurance – and get upset if it is not forthcoming. They are volatile: they take heart, then they despair, then they are filled with hope again. This is the pattern of what Bowlby called ‘anxious attachment’.

But the degree of separation from the parents may be greater. the child could feel so helpless, they become detached: they enter their own world. To protect themselves they become remote and cold. They are, Bowlby says, ‘attachment avoidant’: that is, they see tenderness, closeness, emotional investment as dangerous and to be shunned. They may, in truth, be desperate for a cuddle or for reassurance, but such things look far too treacherous.

The focus of Bowlby’s thinking was about what happens to a child if there are too many difficulties in forming secure attachments. But the consequences don’t magically get restricted only to the age of 8 or 12 or 17. They are life long. The pattern of relating that we develop in childhood gets deployed in our adult lives.

Our attachment style is fed by early experiences: it defines our individual way of being with others. It’s how we sense what other people are up to, how we frame our own needs, how we expect things to go. It’s a pre-existing script that gets written into our adult relationships – usually without us even realising that this happens. It all feels obvious and familiar (even when it is uncomfortable). We take this with us, from partner to partner.

In line with Bowlby’s views about how children relate to their parents, there are three basic kinds of attachment we have to other adults.

Secure attachment is the (rare) ideal. If there is a problem, you work it out. You are not appalled by the weakness of your partner. You can take it in your stride, because you can look after yourself when you have to. So if your partner is a bit down, confused or just plain annoying, you don’t have to react too wildly. Because even if they can’t be nice to you, you can take care of yourself and have, hopefully, a little left over to meet some of the needs of your partner. You give the other the benefit of the doubt when interpreting behaviour. You realise that maybe they were just busy, when they didn’t show any interest in your new haircut, or insights into the news. Maybe they had a tricky time at work, that’s why they are not interested in your day. The explanations are accommodating, generous – and usually more accurate. You are slow to anger, quick to forgive and forget.

Anxious attachment is marked by clinginess: calling just to check where the other is and keeping tabs on what they are up to. You need to make sure that they haven’t left you – or the country. Anxious attachment involves a lot of anger because the stakes feel very high. A minor slight, a hasty word, a tiny oversight can look – to the very anxious person – like huge threats. They seem to announce the imminent breakup of the whole relationship. Anxiously attached people quickly become coercive and demanding and focus on their own needs – not their partner’s.

Avoidant attachment means that you would rather withdraw, and go away, than get angry with or admit you need the other person. If there is a problem, you don’t talk. Your instinct is to say you don’t really like the other person who has hurt you. Avoidant spouses often team up with anxious ones. It’s a risky combination. The avoidant one doesn’t give the anxious one much support. And the anxious one is always invading the delicate privacy of the avoidant one.

Bowlby helps us towards more generous – and more constructive – ways of seeing what our partners are doing, when they upset or disappoint us. Almost no one in truth is purely anxious or avoidant. They are just a bit like that, some of the time. So, alerted by Bowlby, we can see that a partner’s apparent coldness and indifference is not caused by their loathing of us, but by the fact that a long time ago they were too badly hurt by intimacy. They are protecting themselves out of fear. They deserve compassion, not a character assassination.

And it opens possibilities of self-knowledge which can help one reform (if only a little) one’s own behaviour. Perhaps I work so hard because I can’t trust anyone and because a long time ago, I felt that work might help me to secure the fleeting unreliable love of my parents.

Bowlby died in September 1990 in his early eighties, at his summer home on the Island of Skye.

There’s a powerful, modest but very real principle of hope at work in his theories. It took a long time for Bowlby’s ideas about the importance of the early bond between the mother and child to get broader recognition and support. But it did happen, eventually. There was no single dramatic revolutionary moment. Many thousands of people changed their minds in small ways: an idea that sounded stupid, came to seem mildly interesting. The slow revolution took place at dinner tables and at school gates, at conferences in out of the way places and in careful cost-benefit analyses worked out by civil servants. It is a process of social evolution in which there are few obvious heroes and many necessary participants who can never know exactly what contribution they made: so that today a child facing a frightening operation is surrounded by love and kindness and her parents get to sleep in a bed beside her.

How long it took in history for this need to be taken seriously – and so touching it should have been by this particular man, whose family background, childhood, and education could have been expected to close off any such sympathetic insights.

Research shows that in the UK population:

56 per cent are securely attached

24 per cent are avoidantly attached

20 per cent are anxiously attached