Work • Sorrows of Work

The Pains of Leadership

We tend to be pretty clear why it might be nice to be in a leadership role. There’s more status, you get to decide how things should be and – very often – you get paid more too. But there are some dark aspects too.

Here are five of them…

One: You become the object of satire

The rise of satire

It’s deeply pleasing to lob witty criticism. And it’s a natural tendency too.

They’re so good at identifying weakness and failings. The physics teacher is a bit disorganised, wears a jacket with strangely thin lapels and occasionally misses certain portions of his face when shaving.

You might have something of a talent for this yourself. There has always been satire, of course.

The leading politicians are vain and stupid – and usually very ugly as well

In the 18th century, the artist James Gillray portrayed Charles James Fox – leader of the Opposition – as a villainous looking half-wit (he’s standing centre right, slightly bowing, with a blue coat and yellow trousers, with a sword at his side). Everyone in the picture has their faults highlighted. Many look unbearably smug; there’s an individual in a crimson jacket bowing practically to the ground and looking farcically obsequious: it’s William Grenville who became Prime Minister a couple of years after the print appeared.

Gillray was regarded as the greatest satirist of the age. But by modern standards he was operating on a small scale. His works could only be seen by fairly small numbers of people. And his satire sat within a culture in which the traditions of respect and deference were still very strong. For a long time to come, it was easy and normal for those in power to feel that satire, while annoying, wasn’t actually terribly important.

Charles James Fox was generally portrayed in a more flattering light. In any case, his status was not derived from popularity or approval. In 1768, when he was nineteen, his father bought him a seat in parliament. The party he led, the Whigs, was largely made up of his friends and relatives.

This, really, was what limited the power of Gillray’s effectiveness. He could be savage. But the manoeuvring of high politics largely went on without reference to popular opinion.

One feature of the modern world – which mostly is great and very positive – is that people got sick of respect. And the disappearance of automatic respect occurred at the same time as a rise in the dependence of leaders on approval. The development of democracy and of market research has meant that leadership is often vulnerable to what strangers think. So caricature hits harder: it’s a bigger threat.

Homing in on the slightly ridiculous aspects of John Major, the British Prime Minister from 1990 to 1997, (his tendency to look timid, his reputation for naivety, his fondness for the colour grey) wasn’t just a personal irritant. It undermined his public standing and weakened his electoral position.

The moves we see played out at a national stage are also equally directed at more or less everyone who arrives in a position of leadership or authority.

Before you become a leader – or a manager or a boss or an employer – you are on the side of satire. You are very adept at seeing what’s not going quite right, you are good at identifying who to blame and you can see all the mistakes and errors of those making the decisions.

The powerful are the accepted targets of satire

It is hugely to our collective credit that we have come to find it unacceptable for the strong to mock the weak. We now reserve our sarcasm, jibes and fault finding for those we think can take it – and in fact deserve it – because they occupy the privileged positions; those who are in charge in some way are not only fair game: we almost feel it is our duty to voice our criticisms as loudly and as effectively as we can.

The modern world is very alive to the failures of power. Sympathy for the powerful is seen as naive. Which is fine, until you yourself end up in leadership.

You will be misunderstood

It all looks very different from the point of view of the person in the leadership position. Fox certainly had his weaknesses (he liked gambling, he had multiple mistresses, he used to spit on the carpet) but he was also a major advocate of ideas he deeply believed in and knew to be crucially important: the abolition of the slave trade and the evolution of the political rights of the general public. Gillray’s caricatures and mockery don’t touch the substance of what Fox was trying to do or why he thought these things mattered. John Major wasn’t the character the cartoons made him out to be. It is clearly not possible to become the leader of a large modern country without being at least extremely astute and intensely determined. Like Fox, Major’s an example of a very general pain of being in a leadership position: you get misunderstood and misrepresented.

Your flaws are on public display

Your flaws are visible and you won’t be able to do anything about them. You can’t turn you character around. And if you tried you’d get called out for doing that.

The complaints are unrealistic

A complaint is made up of two distinct elements: Dissatisfaction + the belief the problem can be (easily) solved = complaint

We don’t complain when things feel inevitable or unavoidable. You can’t complain if it’s cold in Norway in winter or if Scotland fails to win the World Cup.

For the leader – or manager or boss – the complications and difficulties that lie behind the problems are more apparent than they are to the employees. You become the lightning rod for free-floating dissatisfaction and envy. People will be mean not because you have done anything in particular to deserve their ire, but because you are the nearest available target. We can’t always work out very accurately why we are feeling bothered, frustrated, disappointed or short-tempered. But we need to have someone to blame: and the ideal target is someone who is nearby and who looks like they can take it: in other words, the leader.

Two: You have to become a poet

You may have trained in electrical engineering; your career may have recently focused on supply chain management. But at some point leadership is going to require you to become a poet.

Morale

The reason is to do with morale. One of the key issues in the history of warfare has been the power of morale. At critical moments in battle a single person turning to flee could lead to mass panic, while if one person shows confidence, whole mass of troops can follow.

In Tolstoy’s War and Peace, there’s a critical battle scene when one of his main characters, Prince Andrei, is engulfed in a flood of fleeing soldiers. Desperate to rally them, but alone, Andrei jumps off his horse, grabs the regimental flag and starts shouting and running forwards.

‘Scarcely able to hold up the heavy standard, he ran forward with full confidence that the whole battalion would follow him. And really he only ran a few steps alone. One soldier moved and then another and soon the whole battalion ran forward and overtook him. A sergeant ran up and took the flag that was swaying from its weight in Prince Andrei’s hands – but he was immediately killed. Andrei again seized the standard and, dragging it, ran on.’

It works, the troops gain heart, regroup. It’s a moment that’s really important for Tolstoy to describe because he’s fascinated by the way small things can make a huge difference. He’s describing how the confidence of a leader can be transmitted to the followers.

Morale depends not only on the confidence experienced at a specific moment but more broadly on the conviction that the undertaking is important, and honourable. At the extreme, people will stand in front of tanks, they will put their lives on the line because they believe that something is truly important. We feel committed and ready to make a sacrifice when someone has explained clearly enough why something is really worth doing. Company morale is pride in what is being done and your part in it, the belief that hard tasks can be completed, that it’s worth trying harder, that other people feel the same way and that you can rely on them.

Company morale is created by leaders – though it doesn’t need to be on the scale that take people into battle. It’s not going to involve literally shouting ‘forward lads’ and waving a banner. Instead, the modern leader needs to be a poet.

What poetry is for

Poetry is the ambition of using words to get ideas into our imaginations, so that they influence our lives. It’s based on the realisation that how you present something matters hugely for its effectiveness.

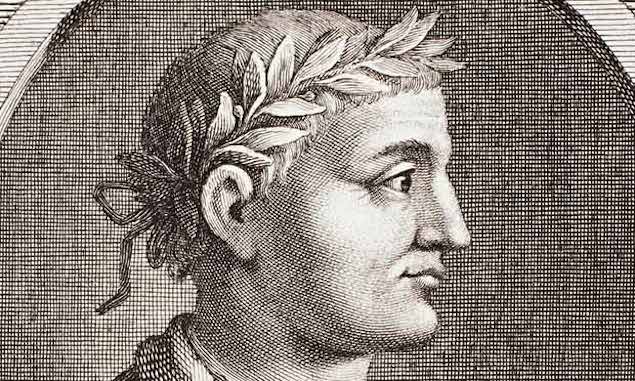

The Roman poet Horace identified two key features of good poetry. Poetry he said should be dulce and utile: that is, it should have utility and sweetness.

Utility

Useful means: that it addresses the problems a person actually has, that are in fact getting in the way. Usefulness depends upon a grasp of what it is that is giving someone trouble. As a generation living after the Romantic call that art should be just ‘for art’s sake,’ it’s surprising and invigorating to find a poet who wants poetry to do things in the world.

Dulce – sweetness or attraction

Sweetness means that it’s something you like: it’s attractive, alluring. You don’t have to try and force yourself to keep going (because you know that, despite the pain, it’s good for you). J.K. Rowling’s work is ‘sweet’ in the sense that Horace meant. Instead of parents and teachers trying to make children read, promising them rewards to read to the bottom of the page, they found that they couldn’t get certain children to stop reading. It was one of the unfortunately quite rare times when something very worthy (learning to read) was also compulsively attractive.

Horace’s ideas about poetry show why certain poems work so well. For instance, “They Fuck you Up” by Philip Larkin.

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Its usefulness is that it says you can’t help it that your parents let you down and that they didn’t mean to, they couldn’t help. The failures of your parents were not a specific failing of them, but a sad and entrenched feature of the human condition. It’s not necessarily useful for everyone – but a lot of people DO need to hear this message again and again: they let you down, they didn’t mean to; their parents let them down; if you have kids, you’ll let them down and you won’t mean to either.

Its attraction – it’s direct and swift and easy to remember. In fact, the opening two lines are now the best known lines of 20th century English poetry.

sweetness + usefulness = great poetry and great memos and power-point presentations

The leader needs to be a poet because they need to make the project of the company motivational; out of the millions of things they could say (the shareholders are pleased; our copper wiring is 3% cheaper than our rivals) they need to find the things that speak to the heart of the people they lead.

Three: You have to leave your old friends

In the 19th century, when people immigrated, they knew that they would probably never see their old friends again. They were taking a step with major consequences. They were acutely conscious of the scale of what they were doing. They had sold their cottage; they had packed up all their belongings; they could feel the slow movement of the ship. They had a fourteen week journey before them.

They knew there was no going back

There are many steps in life which have a similar character – they take us to a new world from which we can’t return. But they are usually less overtly dramatic. And so the trauma is not so easily recognised – though we suffer just the same.

It’s the pain of the process of maturation. When you become an adult you can’t ever really be a child again – though you will often be childish. You won’t ever again feel the complete ease that comes from the assured conviction other people will look after everything; perhaps climbing a tree will no longer feel like the most wonderful adventure in the world; a chair will never again be a sailing ship, or the space between your bed and the wardrobe, the Pacific ocean.

To become a leader is to undergo a change of this kind. Some earlier (and very nice) versions of oneself will have to be packed away. The sarcastic genius may not be coming back. The people you used to share a lot of good times with at work will think you’ve changed – and become more distant; you won’t be such fun to be around. You’ll seem colder. You’ll lack a sense of humour.

David Brent: paying the price for staying his old self

You will have to function without being understood by those you used to be close to.

Four: You need to be like Jesus

Irrespective of one’s religious beliefs, it’s clear that Jesus was one of the great leaders of all time. One of the main secrets was he united two characteristics that generally seem opposed.

He was powerful

The central idea of Christianity is that Jesus is the son of God and has immense power.

‘He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead’

But at the same time…

He was one of us

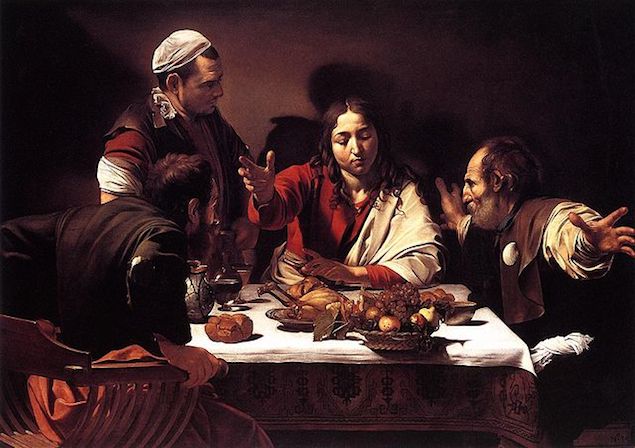

The stories of the life of Jesus stress how normal and average he was in lots of way. His parents weren’t at all well off. Until he was thirty, he worked in his dad’s carpentry shop. One story told of how some of his supporters were making quite a long journey on foot to a place called Emmaus. Jesus joins them – in disguise. They chat with him, they talk about a lot of things. And they just think that he’s an ordinary, interesting man. It’s only when they get to their destination and have a meal, and Jesus blesses the bread in his special, characteristic way, that they recognise him.

The great sellers of Religion – like the baroque painter Caravaggio – loved this story. They realised what a key selling point the ordinariness of Jesus was. You could sit down and have a meal with him. He had the same kind of worries and troubles as you. He understood, he knew what your life was like.

The idea was that Jesus won the trust and loyalty of his followers at a very personal level. He didn’t simply impose or demand or assert his superiority.

The Jesus-type role (combining being ‘above’ and being ‘with’) is demanded by the modern workplace. To be effective, leadership has to be founded on personal trust. A great complaint about leadership is that the leader doesn’t understand, or has forgotten, or doesn’t care about what it is like for those lower down the system.

It’s just inherently difficult to be both of these things at once: to be intimate and also be in charge. Traditionally, these are distinct roles. We’re not especially cut out to do the two of them at the same time.

People in authority who have understood the moral of Jesus’s story know how to do leadership and ordinariness.

Just out for lettuce, like everyone else

When she takes public transport, the Queen of England is at one level doing a very normal thing. But because she does it, it is – of course – astonishing: because she could easily afford to go by helicopter, because she is the woman who was crowned in Westminster Abbey, Queen of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the sea, defender of the realm and of the faith.

Now she’s on the train in the seat next to me

What touches us, even if we don’t usually spell it out, is that she is both the sovereign and a passenger at the same time, both extraordinary and normal.

Hierarchy is a deeply painful aspect of human society. There are good reasons why wholesale equality isn’t practical, but the longing for understanding and sympathy by the powerful towards the less powerful runs deep. That’s why it is deeply moving – and plain reassuring – if we see someone who could fly by helicopter take the train. It bodes well for the world.

We live in societies that are officially egalitarian and meritocratic. Yet we are endlessly exposed to massive differences in wealth, power, status and fame. We’re fascinated by the lives of top people. Yet we are troubled too. Do they understand? Do they know what it’s like? Any hints that they do are deeply significant.

When the Queen takes the train, she is bridging the world of history, grandeur, money and power – and the world of everyday life. The cynical (or just ambitious) voice might at this point say that there should only be average, normal, egalitarian things. But as this is unlikely to happen any time soon, what we desperately need is people at the top who properly understand their responsibilities towards the many. The Queen knows this, and that’s why she is rarely more appreciated than when she takes her place in a second class carriage of a provincial English train.

Five: You will be hated: Learn a lesson from the Home MBA

There’s one arena where we don’t nowadays expect to learn very much that could be useful to us in the workplace: home.

Home is meant to be a location for relaxation, sweetness and fun, a break from the arduousness of the office. Furthermore, in so far as there are children, modern parents are not expected to ‘lead’, merely to try to make life as pleasant as can be for young charges.

© Flickr/Taichiro Ueki

The notion of paternalism – of a more authoritative kind of domestic leadership – has become poisoned and the target of constant scepticism. When, in 1964, Bob Dylan sang to a generation of parents that “your sons and your daughters are beyond your command” (The Times They Are a-Changin’), he was counting on an instant recognition of the multiple failings of parental authority.

The difficulty of parenthood is that one is asked to be the guardian of the long-term interests of someone who will be absolutely convinced, on multiple occasions, that one is deeply and viciously wrong (about the computer, the sleep-over, the car use…). And indeed one may be, which doesn’t preclude the need to come up with a plan and a principle.

It is always a matter of surprise to a new parent how much they can love their child and also, how weird it is to have to say ‘no’ to them – and then be the target of special hatred by someone they would lay down their life for. The role of a parent is a training ground in the inevitability of taking unpopular decisions – and in not expecting sympathy or gratitude for a very long time indeed.

It might be 25 years until they understand why you took a certain decision – let alone grudgingly acknowledge there might have been a point to it.

© Flickr/Thor

Modern leaders and modern parents aren’t inclined to draw parallels between their activities; to think that “my children are my employees” and “my employees are my children.” Yet it’s mere squeamishness on our part that we don’t see domestic life as the training for the office (and for leadership roles especially) that it might be. There are MBAs to be earnt at the kitchen table and honed amidst the anguished screams around bedtime and teeth-brushing.

Conclusion:

There’s a habit of stressing the benefits and understating the negatives of major developments in life. Weddings generally exaggerate the joys of coupledom, becoming a parent is generally discussed only in its fulfilling and exciting aspects. It’s not that there are no good points, of course. It’s just that on their own they give an unhelpfully unrealistic account of what we’re getting into. They raise expectations too high. So by comparison, being married or being a parent is a let down. The risk is that we get very disenchanted and panicky when things turn out to be very much tougher than we’d anticipated.

The position of being the boss, joining the leadership team or generally having more responsibility and power seems enviable. But as we’ve been seeing, it’s got considerable difficulties and troubles that come with it too.

If we assume that something ought to be quite easily within our grasp and not too difficult to do, we get panicked and worried if we suddenly find we’re having a very hard time. We think that there must be something particularly wrong with our characters, we fear we’re not cut out for the role, that we don’t have what it takes. But our feelings are not actually fair to ourselves. They are really caused by our initial expectations than by any special defect in ourselves.