Work • Utopia

Utopian Education

It is almost universally agreed that education is hugely important. But we are not particularly sure what we want from it. Our large commitment to there being good schools ironically has not been matched by concern about what they are for.

The aim of education is to prepare students for adult life. So the role of schools should be thought through only after we have identified the challenges of adult life. If school is essentially conceived as a training, we need to explain what it is training for. What are the relevant difficulties and challenges that we need to be equipped to deal with?

There are two fundamental tasks education should help us with: working and sustaining good relationships.

These goals are generally acknowledged, but in a hazy and distant way. We hear that studying literature might help the imagination or that knowing some history will make us more capable of understanding current societies. But these pieties don’t generally rise above the level of generalisations – and are not explored with thoroughness in the actual curriculum. We do not assess courses and classes as we should – according to the help they really do provide in the task of being a good adult.

If we work backwards from life, it is clear that schools fail all but a tiny portion of their students. This is a generic problem, as much in evidence in posh, highly academic private schools as in more deprived, government-run ones. Trouble around work and relationships remains very widespread indeed. Human ingenuity, energy, goodwill and talent is still being lost on an industrial scale.

To get more ambitious about education doesn’t necessarily mean spending more money, building more schools, employing more teachers, or making exams more difficult. Rather, it should chiefly mean focusing more clearly on the real purpose of education.

In the Utopia, unlike today, schools would be designed by people who asked systematically about the main problems in people’s work and home lives – and then worked backwards to put adequate, thoughtful responses in place in the training years. In order to address our needs, a future national curriculum might specify that the following subjects would be studied:

Capitalism

There is at present a conspiracy of silence around the economic system we live within. We find it hard to change its bad sides (or defend its strengths) because we simply cannot understand how it works. Nothing captures this more than that we currently study maths when, in truth, we should really (from a very young age) study the one thing that maths is used for by 99% of the population: money.

In the Utopia, there would be extensive classes on the workings of Capitalism. One would study how profit occurs, why some areas of activity are much more profitable than others and how economic opportunities arise.

The aim would be to demystify the economy and to educate citizens to be realistic both about the opportunities they’ll have and the economic constraints they’ll face. Students would be taught to see that an economy is ultimately always the creation of society, not an act of God or nature. This is crucial since so much of how our lives pan out is broadly determined by the kind of economy we live in: why are there more jobs in nail bars than in therapy rooms; why do footballers make more money than brain surgeons and why do so many jobs have titles like assistant regional distribution executive, rather than carpenter or farmer? All this and more would be explained.

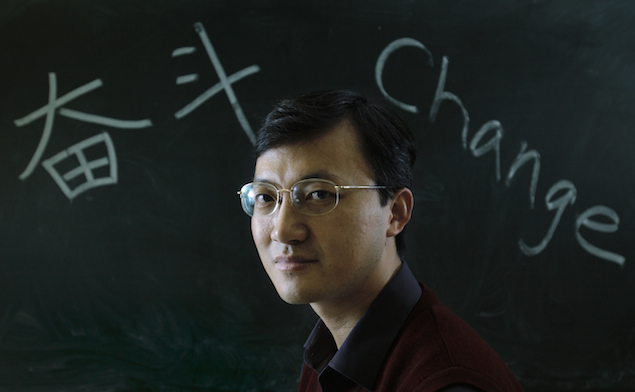

An important unit in this subject would be the study of change in society. What enables revolution (whether of a commercial, ethical or political kind) to occur? A great deal of attention would be paid to the fact that mostly our frustrations and disappointments do not directly lead to improvement. And yet – this point would be written up in large letters in every classroom – improvement truly is possible.

© Toronto Star/Getty

Under the heading of change, students would study material which, at present, is classed as history. They might look at the Chartist movement of the 1840s, the Russian Revolution or the Reformation, but from a totally practical point of view, as potential revolutionaries themselves. What lessons could one learn from each event? One would never (during one’s whole time at school) simply try to understand the past for its own sake. One would only ever investigate it as a series of case studies from which one was trying to extract useable wisdom.

Business

In this set of courses, students would learn how to deal with the world of work.

They would learn what the options really are – and the relationship between early choices and subsequent destinies (the purpose would be to reduce the chances of anyone in the future waking up aged 48 in despair, wondering what they had done with their life). They would learn what a business idea really is. They would discuss productive and less productive sectors of the economy. They would understand the role of cash flow, HR, leadership, marketing and competition. They would learn how to deal with colleagues, burnout, envy, office politics, interviews and sackings. They would spend three hours a week exploring and discussing what they might do with their future.

All this would begin from the age of 8 – rather than being left as a set of arcane secrets available only to an elite who can embark on a ruinously expensive MBA aged 27.

Consumption

In the Utopia, the view of what you’d need to learn would be very broad. It would reject the Romantic assumption that we each hit, by instinct, upon our own understanding of what is right and good for us. Instead, the education system would work on the assumption that we can learn how to enjoy ourselves, what to admire and how to flourish.

Schools would pursue these topics with an eye on students’ actions as consumers. The economy we get depends very largely on what we want to pay for (McDonald’s, Easyjet or…). So consumer education is vital, and in no way a trivial after-thought.

This course of study would explain the relationship between consumption and flourishing. The underlying idea would be that one ought always to buy the things that have been ethically produced and that help one to become a better version of oneself.

There would be units on: what to read, what kind of clothes to buy, what films to see, what TV programmes to download, what food to eat, what furniture to invest in, where to go on holiday. In each case, students would learn to ask how a given purchase would meet their needs. Courses on consumption would often overlap with the self-knowledge lessons [see below].

In special classes, specific items – a coat or a car, a novel or a sofa, a water jug or a Picasso poster – would be analysed in terms of their potential to fulfil us. Students would be required to analyse what kind of person would benefit from ownership of these precise items. They would have to define the need which consumption meets.

The purpose would be groundbreaking: not simply to generate infinite consumer choice, but also to bring up generations that would know how to choose wisely.

Self-knowledge

The self-knowledge classes would be central to the whole system of education. Students would be introduced early on to the idea that we are extremely prone to misunderstanding ourselves, that we do not automatically have a correct or insightful view of what we are up to, or are bothered about or grasp.

They would be taken through ideas (many derived from psychoanalysis) as to the roles of delusion, defensiveness, projection and denial in everyday life.

There would be individual tutors on hand with whom students could work to develop a map of their characters, with particular attention paid to their neuroses and defences. After this module, students would quite easily, and with good cheer, be able to describe in what ways they were a little mad (as we all are). They would know rather a lot about how they were difficult to live with, and what sort of people it did them best to spend time around.

A crucial unit would be devoted to career self-knowledge: what job are you best suited to do? Ending up in a job that you like and feel is worthwhile is a huge – perhaps the biggest – attainment. Self-knowledge in the area of employment offers protection from the ravages of envy. We get less bothered by the fact that others have more glamorous, more highly paid careers if we see clearly why such options would not really fit our characters or temperaments.

Relationships

School is a preparation for coping with the difficulties (and making the best of the opportunities) of adult life. And the Utopian society would be intensely aware of the social and individual cost of every unhappy relationship. So there would be huge emphasis on gradually acquiring the knowledge, attitudes and skills that help people live well together.

In the early years, getting on with others would be a central focus of attention. After puberty, the focus would be on relationships. There would be units on kindness and forgiveness. Pupils would pass not when they know the theory but when they could demonstrate in practical tests their actual readiness to forgive when there are reasons to feel righteous and to be kind when its tempting to be vindictive. Techniques for the reduction of anxiety would receive much attention.

Under relationships there would be classes on how to have an argument, on the successful ways of persuading and on allowing oneself to be persuaded. Students who did well would feel some of the same glory as is currently accorded to those who pass maths exams with honours.

Conclusion

In the Utopia, school buildings would also be a focal point of civic pride, widely admired for their beauty and serenity. Running a school would be one of the most prestigious and well paid jobs. Only the most wise, kindly and insightful people would be employed as teachers.

© UIG/Getty

It would not only be children who went to school. Adults in general would see themselves as in need of education. One would never be done with school. One would stay an active alumni, learning throughout life. In the adult section, there would be courses on how to converse with strangers or how to deal with the fear of getting old; how to calm down and how to forgive. There would be career advice for the middle-aged. Schools would be where a community gets educated, not just a place for children. So children would feel that they were participating in the early stages of a life-long process. Some classes would have seven-year-olds learning alongside fifty-year-olds (the two cohorts having been found to have equivalent maturities in a given area). In the Utopia the phrase ‘I’ve finished school’ would sound extremely strange.

© AFP/Getty

Furthermore, education would be viewed in a properly holistic way. It wouldn’t just be something that took place in classrooms. Anywhere where citizens were influenced and conditioned would fall under the remit of the education department. So the department would control media, broadcasting and the arts, because newspapers, galleries, museums, theatres and television channels would be seen as essentially educational – and judged, developed and controlled so as to maximise their effectiveness in teaching the things we most need to learn. There’s little point spending millions educating the citizenry in wisdom in classrooms then allowing a tight-knit group of banal and venal television executives or newspaper proprietors to pump out material that directly undermines the preceding effort.

We’re so hung up on the challenges of running a massive education system, we’re failing to pinpoint the real source of our problems. It isn’t primarily about money, salaries, discipline… Troubles here are only a consequence of a more basic difficulty that precedes them all, namely, right now, with no one quite meaning for this to happen, but with untold consequences and costs,we’ve got the wrong curriculum.