Self-Knowledge • Know Yourself

What Brain Scans Reveal About Our Minds

Two photographs deserve to be counted as among the most significant of the twentieth century. The first was taken on December 24th, 1968, by the astronaut William Anders as the Apollo 8 spacecraft orbited the moon – and showed off the earth as the legendary pale blue dot in an infinity of emptiness.

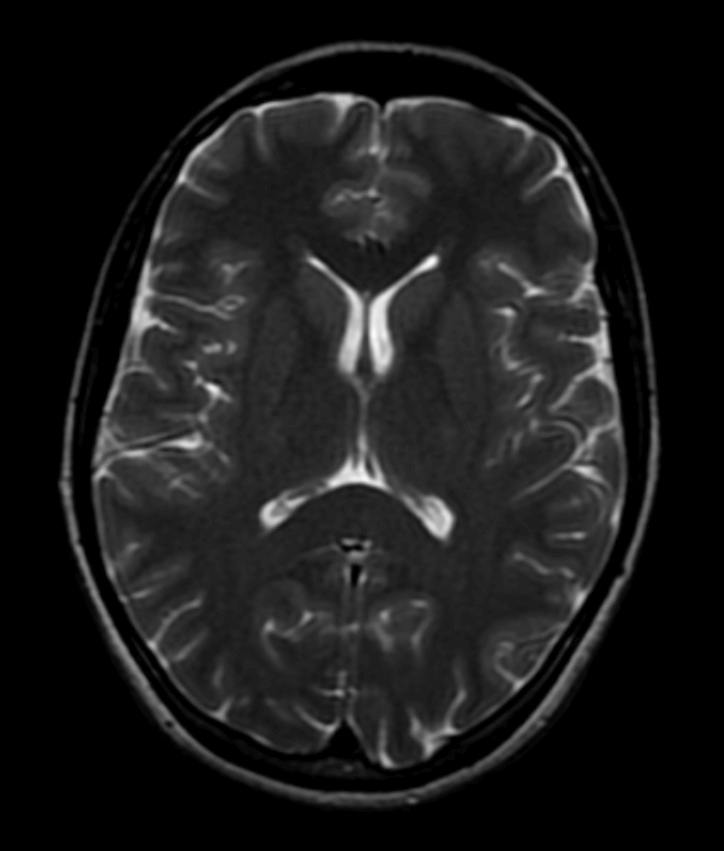

The second image – far less well known – was taken in 1978 by a team of scientists led by Hugh Clow and Ian Robert Young at EMI Laboratories in England and revealed a cross section of the human brain as seen through the electronic eyes of an MRI scanner.

MRI technology proved to be a revolutionary advance on the CT scans that had preceded it because it created brilliant contrasts, displaying areas that were high in water and fat in white – and those low in water and fat in black. It granted one near-perfect vision over parts of the brain that had previously been known only from an anatomist’s slab: the cerebellar cortex, the occipital lobe, the hypothalamus and the corpus callosum.

MRI gave our species a new degree of insight into itself. Everything that homo sapiens had ever done, thought about, dreamt, imagined, every act of love, bitterness, vengeance, generosity and wonder had passed through this instrument now resplendently displayed against the scan’s cosmic darkness. This is what would it would have looked like inside the craniums of our ancestors who crossed the Torres strait, who colonised the Mongolian steppes, who guarded Jesus, who wrote the Magna Carta, who defended the last remaining Aztec temple, who cracked the Rosetta stone and who invented the bikini.

But after we have been awed all we can be by this extraordinary watery bundle, this fifteen centimetre long, 1,300 gram packed with 86 billion neurons, this simultaneous creator and interpreter of what we call reality, we can admit that this machine nevertheless presents us with as many problems as it does solutions.

The organ is – despite years of patient education and encouragement – wholly uninclined to think logically through its dilemmas. It is primarily an instrument of instinct, substantial portions of its lower basal folds operate with the rabid ferocity of those of a lizard or a rat; it responds at lightning speed to threats and lures with impulses honed over a 200,000 year history but it is entirely reluctant to stay still for a while, pull out a pen and paper and analyse its feelings and desires with anything resembling rigour. It jumps into marriages, it fires off emails, it starts lawsuits, it places its hand on others’ knees, it blurts out its rage, it stuffs itself with sugar, it makes accusations – and thereby repeatedly destroys the foundations of earthly contentment. All the calm and forethought, the perspective and resilience that we would need to steer us through our difficulties are missing from this organic structure. Our wars and slums are visible from outer space; this is where they have their origins.

Sadly, this soupy walnut cannot recognise its worst proclivities and take protective measures against them. It can have been around for fifty years before it comes to basic realisations about its workings: how much it gets wrong, what it misses, where it exaggerates, what it underplays, how others are likely to see it. A stranger can know more about it in a matter of minutes than its owners ascertain in decades. We are consciously aware of only a tiny proportion of the ideas and drives that course through us; at rare moments – perhaps when falling asleep or waking up at an unusual hour – we get a hint of how much there is in our minds that we cannot properly touch; how many stray memories and bittersweet recollections swirl in the lower reaches of consciousness. Nothing has quite disappeared; nothing ever leaves us fully alone; we are filled with ghosts.

More pointedly, the machine is affected by events in its past which gravely distort its assessments of the present. It may come to distrust all men or all women because a few examples once caused it harm. It may lose all ability to smile and be hopeful because it was attacked in its third year or harshly spoken to over its initial decade. It can expect that everyone will be mean to it because – at a formative stage – one or two people were; it can develop a conviction that it is unworthy and should be extinguished. It may be tempted to sabotage itself at moments of its greatest triumph. It can run away from kindly people from a conviction that it doesn’t deserve anything but hurt.

The mind is lazy too, it can’t work up the energy to interrogate itself on its wishes and put in motion plans that could nimbly realise them. It craves distraction just when it brushes up against important ideas. Only one mind in ten million delivers on its actual potential; what we call ‘genius’ is the rare will to transcribe faithfully the best ideas that course through the mind and that normally refuse to be pinned down – even though the raw ingredients for such ideas is present in everyone. We are almost certain to die having mined only a fraction of who we are.

When the mind falls seriously ill, there is almost nothing to be done. Our science is stuck at the level of medieval dentistry. Somewhere in the folds of our cortex, out of reach of medicines or therapies, lie compulsions to despair, to refuse help, to injure ourselves and to remain addicted; we grow convinced of the worst plots and vendettas, we may – after years of suffering – see no alternative but to fire a bullet through our own cerebral tissue.

So, though a technical and artistic triumph, a picture of the inside of our minds can only be greeted with ambivalence at best. We are seeing at once the creation that underpins our most majestic moments – and a piece of unreliable matter that keeps us mired in conflict, sadness and anger and is incapable of doing justice to our underlying brilliance.

The real response to this image should be compassion, that we need to do so much with a tool that is – at best – only half fit for the task: that with this piece of cobbled together intermittent, bug-filled hardware, we have to decide whom we should trust, what we should put our faith in, how we can manage our desires, what course of action we should follow. In another million years, we will have evolved out of the constraints of this particular model, we will look at it with the same pity as we now direct to our early computers or the ill-adapted fins of early sea creatures, we will at last have minds that can help us accomplish what we actually need of them; that won’t just throw up mirages of happiness to tantalise us and then step back and watch us stray and stumble, that will be kind and nimble enough to navigate us through the shallows and the darkness we actually face.

We are likely already to be experts at self-flagellation; masters at itemising the many ways in which we are despicable, undeserving and shameful. But after we have run through every argument about why we are so ignoble and so daft, we should spare a moment to consider that the fault does not lie with us alone. Nature equipped us especially badly for the tasks we were obliged to take on, we never had much of a chance, we were never granted the sort of brains we would have needed not to fail and not to suffer.