Work • Good Work • Capitalism

What Good Business Should Be

Business is a central human activity. In some form or another most of us are involved in business activities most of our lives. It’s the primary mechanism by which human energy, talent and intelligence is harnessed, put to use and rewarded. But anti-business feelings are widespread. There’s distrust of large corporations, doubts about the profit motive. We have the nagging worry that the Capitalist approach to economics might not be properly serving our best collective interests. And yet a world without business seems scarcely realistic.

As with many of our biggest challenges – cities, government, the economy, families – we can’t (and don’t really want to) abolish the thing that’s giving us trouble. We want to improve it. We want finer cities, better government, less anxious families. So too with business. The goal isn’t to get rid of commerce, but to get it to serve our long-term interests better.

Business does not have to be bad. We should try to get business right. To do this, we have to follow twelve principles of good business.

One: Make profit from needs, not from desires

Business means – at base – selling someone something. From the pure point of view of commerce, it doesn’t much matter what you deal in: you could be selling shoelaces, crude oil, nanotechnology, handguns, the collected works of Tolstoy. What counts is how profitable the transaction is and what return it brings on invested capital. Entrepreneurs identify peoples’ desires (so long as they are not prohibited by law) and seek to service them profitably.

It might sound fine, but this is the classic defence for selling bullshit. There are plenty of people who desire the low end of the press, crass television, substandard food, bloated, ugly McMansions, two-million-euro watches and cars that look like stealth fighters. So, inevitably, businesses will evolve to profit from their wishes. Capitalism has not traditionally been interested in whether these are sensible, admirable or worthy desires. Its aim is neutral: to make money from supplying whatever people happen to be willing to pay for.

Philosophy, by contrast, has long recognised a crucial distinction between desires and needs:

A desire is whatever you feel you want at the moment.

A need is for something that serves your long-term well being.

And it’s our needs that are required for a satisfying, fulfilled life (which Plato, Aristotle and others call a life marked by eudaimonia).

Unfortunately, desires and felt wants are not reliable guides to a good life. We know this painfully well in small matters. You desire more chocolate biscuits; you want everyone to fit in with you; you feel like lying in bed all day. Desires hog all the attention and it’s very easy for us to lose sight of our true needs. This is no one’s fault. It’s a natural cognitive flaw: the outcome of evolution. In the state of nature, desires don’t split off from needs. The human desire for sweet things served us exceedingly well for almost all of our history: it led us to like bananas and coconuts and apples – things that are very good for us. It’s only in artificial environments that desires can become a problem. The moment sugar refining was invented, the desire for sweet things became a mortal danger. In advanced technological civilisation, our desires can work directly against our needs.

The problem is, we’re more aware of our desires than our needs. Desires are obvious. Needs might not be.

Capitalism goes wrong when it exploits this cognitive flaw: large numbers of businesses sell us stuff that we desire but which (in all honesty) we don’t need. On longer, calmer reflection we’d realise those things don’t actually help us to live well.

Sadly, it’s easier to generate profits from desires than from needs. You can make much more money selling bad ice cream than by marketing Plato’s dialogues.

In a utopia, good businesses should be defined not simply by whether they are profitable or not; but by what they make their profit from. Only businesses that satisfy true needs are moral.

Two: Successful capitalism requires education not instinct

Business is guided, in the long run, by demand. And Capitalism tends to assume that we intuitively know pretty much what things we should have in our lives: where to go on holiday, what clothes to wear, what to eat. We might need some emotive prompting, perhaps. But our current economy is suspicious of the idea that people might need to think rationally and exhaustively about a holiday, a meal, a jumper, a car. (Not least because one might come calmly and reasonably to the conclusion that a proposed purchase will contribute little or nothing to one’s long-term benefit.) In strict capitalism, it sounds heretical to say that demand might be wrong or mistaken. How can you possibly say that someone has bought the wrong thing: how snobbish, how mean. Yet, if we look at this issue modestly – and think only about our own lives – it’s obvious that a person can purchase the wrong things when the person in question is oneself.

Good capitalism requires that we address two, core educational needs. Getting us to focus on what we really need, what the real challenges in our lives are. And getting us to focus on the value of particular goods in relation to our needs: that is, how do these particular purchases help with eudaimonia?

Businesses can get more meaningful when there is more education of this kind around. The better educated a society, the more likely it is that better businesses will have a dominant position.

There’s a parallel with democracy: you can’t have a functioning democracy without an educated electorate. Equally, though we haven’t given the point due recognition, you can’t have a noble kind of capitalism without an educated consumer base.

So, in search of a better economy, we should direct our attention not simply to shopping centres and financial institutions, but to schools and universities and the media. The shape that an economy has ultimately reflects the educated insights of its consumers. When people say they hate consumerism, what they often mean is that they are dismayed at peoples’ preferences. The fault, then, lies not so much with consumption as with the preferences. Education transforms preferences not by making us do what someone else tells us. But by giving us the capacities and skills to understand more clearly what we genuinely do want and what sort of goods and services will best help us.

Three: We need to be seduced by the good not sent on a guilt trip

Those who want to improve the economy often seek to focus attention on cruelties and injustices which may lurk behind apparently innocent purchases.

They point out you are not just buying a shirt, you are ruining someone’s life. They remind you that the grapes that have come half-way round the world to grace your table are helping melt the Quelccaya ice cap in Peru. Some people are responsive; feeling guilty, they change what they buy.

But mostly we’re not like that, we have a much quicker way of dealing with guilt: we ignore it, we switch off, we get defensive and say we don’t care; we tune in to something more cheerful. So, making people feel guilty can actually entrench their behaviour.

We really do need to do something about the ice and the appalling work conditions. But the starting point has to be indulgence towards the way our minds work. We are wired in unhelpful ways. If we are going to be interested en masse in the defrosting poles and the lives of distant others, we need to take our fragilities on board and therefore get serious, very serious, about trying to make these things not just ‘important’, but also beguiling.

Instead of moralists seeking to modify behaviour by inducing guilt, we need rival businesses seducing customers to buy more admirable products. We need to be eased away from problematic purchases by an environment in which it is more attractive to do the right thing. Good businesses reward us for the slightly higher price we will inevitably have to pay or the little inconvenience we will need to put up with. They make local, seasonal fruits feel more chic; so our pleasure in distinction, fashion and style lead us to renounce the far-flung grapes (and their air-miles) and go instead for a nearby apple.

Four: The task of advertising is to keep our true needs in view

Advertising can often seem like a low, slightly shameful activity. The fear is that advertising creates false wants: it promotes desires we would otherwise never have. It encourages dissatisfaction, envy and frustration. It stimulates vain and shallow attitudes.

But if we strip it back to essentials, advertising is basically the attempt to get us to see that something could be important to us. They might not often be getting it quite right, but the underlying idea – of drawing attention to needs – is not in itself bad.

The advert says, in effect, you might not have realised just what a good contribution this kind of thing could make in your life. Works of literature and art are often making the same sort of move. Tolstoy’s novel The Death of Ivan Ilyich tries to get us to see that we need more compassion in our lives. In a crucial sense the novel is an advert for compassion.

But, unfortunately, the more noble products have often been caught up in a snobbish (and misguided) disdain for advertising. They renounce the task of telling the world why they are good, desirable and attractive – and how, in fact, they will contribute to the good life.

There are many things we might buy, which could to a lesser or greater extent help us live better lives. And advertising wants us to see the ‘eudaimonic’ potential of a particular product. Sometimes, of course, an advert might wildly overstate the case. It tried to get us to believe that a certain brand of champagne will improve our social life or that better car insurance will lead to a happier family. The problem is one of exaggeration.

Yet, if there are cases in which we tend to overestimate how much a product can help us, there are also many cases in which we significantly underestimate our need for some other thing. Our society has invested heavily in advertising chocolate bars but hardly at all in advertising couple therapy – even though the latter may have as much (or probably a great deal more) to contribute to our well-being.

Psychotherapy, for instance, remains comparatively marginal as an industry, while confectionery is massive, because we are so much more alert to our interest in sweets. In good business, advertising is a serious and noble undertaking. It is the attempt to understand and to explain the way a product or service really can assist us in our flourishing. And to get that valuable, important message across despite everything else competing for our attention.

Five: Advertising comes first

The people who make adverts are often extremely good at homing in on what we truly want.

The team advertising VW cars decided not to concentrate on the durability of the rubber from which the tyres are moulded or the excellent quality of the wiring. They understood that deep down most people are only moderately interested in the mechanics of cars. And that often our desires are not focused so much on automobiles themselves but on the kind of life we think we might be able to lead around them.

VW adverts understand how great it would be to be part of a warm, funny, down-to-earth extended family. They have glimpsed the truth about our longings. And then, they have the somewhat strange task of slotting in the actual product and insinuating that the car belongs naturally in this great family.

Traditionally, businesses develop a product and then consider how to advertise it. The people thinking imaginatively and seriously about family life are brought in only at a late stage of the enterprise – after the people dealing with things like fuel efficiency, electronics, and anti-corrosive paint have done their work.

In a more evolved version of capitalism it would be the other way round: businesses would start by considering advertising – in the sense of identifying what it is, truly, that people want – and then focus on product development. They’d start with the idea of the strong, warm family and seek to develop the products that would most contribute to that. The adverts are far ahead of the product. We need to catch up.

Six: A good business combines command of fun and goodness

Usually fun and goodness have a tricky relationship. Things which are fun are intuitively, naturally alluring, warmly engaging, captivating: cartoons, sweet drinks, alcohol, lazing about, action films. While the things that are good require a bit more effort, self-control and attention. They may be worthy, but they are dull. And this is broadly reflected in patterns of business success. It’s easier to produce things that appeal to the less-elevated sides of our character. Bigger fortunes are made selling french fries than stone-ground bread or made running gossipy, sensationalising newspapers than serious broadsheets; pubs make more money than bookshops; status driven-luxury brands are more successful than fair trade co-operatives.

Logically, it must be harder to make things which are both appealing and good. Because the enterprise needs to solve two big problems rather than just one. The moral producer has to master both fun and goodness. Lots of people have mastered fun; and a fair number of people have mastered goodness. But very few have mastered both. It’s not impossible. It’s not that goodness makes fun impossible, or that fun rules out goodness. It’s just that the target is smaller – harder to hit.

This integration of fun and goodness is crucial because whether we like it or not we live in a competitive world. Those who advocate goodness have tended to be hostile to the idea of competition; and so they leave the public realm in the hands of those who only care about profit.

Seven: Know yourself

Along with love, finding a job that’s right for you is one of the areas in life in which self-knowledge is crucial. It requires a realistic understanding of one’s needs and potential – and, especially, of one’s limitations. There is a dangerous abandonment of career choice to ‘intuition’. Each person is supposed to work out for themselves what to do with their working lives.

There is continuous loss of potential. Someone who might be a fantastic maths teacher spends many years as a dissatisfied and not terribly effective lawyer. A dental technician might have been happier as a gardener. A chair designer might not have thought of entering into politics (to which, in fact, they could have contributed very well). Someone ends up as a professor of literature when their sensitivity to character and irony might have been invaluable in the higher echelons of the police service. Our career choices are troubled by lack of understanding of what our genuine strengths are (which is not a matter of how we happen to feel but of how we rate relative to others) and by lack of understanding of where those strengths can best be deployed. And we are distracted by the very imperfect distribution of status.

For good business to flourish, we need to give very much more attention to a fundamental question: what kind of job should each person do.

Eight: In good business a job serves the true needs of others

One of the primary things people want from work is a sense of contributing to the collective good. That’s not surprising. Work is just purposeful effort: and we long to feel that what we have put our energy and time into is worthwhile. Our labour should be well directed. Of course we want to be personally rewarded, but we are profoundly social creatures and we need to sense that we are valued members of a community and doing our bit. People have an incredibly strong urge for meaning. Essentially, meaning comes from improving the lives of others, either by reducing suffering or increasing noble pleasures.

The problem is that a lot of jobs do not provide this. A big source of workplace suffering is the fear that our jobs are meaningless. It’s our recognition that there isn’t enough connection between our daily labour and the human good. We are employed, yet it is misemployment.

Good business is directed at genuinely helping people and makes a profit on the assumption that what it offers is helpful and so people are right to pay the price. The employees of the firm don’t simply get rewarded by getting paid; they get rewarded by experiencing themselves as assisting in making genuinely good things happen for other people.

Nine: In good business, externalities are properly identified and accounted for

Typically, the price of a product or a service does not actually take into account the full cost of producing it, because some resources have – inadvertently – been given free to the producers. In the 19th century, for instance factories were often allowed to discharge raw effluent into streams and rivers. They didn’t have to pay to have their waste products treated and disposed of safely. Society was, in fact, subsidising their products – but without having particularly intended to do so. So too with financial institutions that are too big to fail: their costs are reduced because they don’t have to provide for themselves all the safety nets they should in truth.

A good business culture is one that accepts the true cost of production and supply and in which everyone involved in the supply process is treated decently. The just price reflects these costs. In a good society, the just price would be the normal price.

Whenever a supplier provides something below the just price, they have to be taking a shortcut somewhere. They have to be offloading some cost; they must be treating someone badly; they must be skimping on quality without admitting it.

As we get collectively nicer, we care more about the path a product took on its way to our lives. The long, expanding history of niceness extends our concerns to the well-being of others who are connected somewhere along the supply chain.

In a good business, the price of the product is just, that is, it reflects the cost of supplying a thing while treating everyone decently along the way.

Ten: Do good through accumulation, not through dispersal

The standard trajectory of philanthropy is: acquire a fortune by rigorous means and then disperse it to good causes. Plutocrats like Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick or Andrew Mellon made money in so-called ‘low’ areas of the economy like coal mining, railways, abattoirs, and packing factories – areas where you squeeze costs as tightly as you can and are always looking to reduce benefits as much as possible. However, once the money is in the bank, these rich people wholeheartedly turn their attention to ‘higher’ causes – among which art (and all that it celebrates, like kindness, beauty and tenderness) looms especially large.

It’s not ideal to ignore the higher needs of mankind for many decades while pulling together an astonishing fortune and then, later in life, suddenly to rediscover these higher needs via an act of immense generosity towards some localised little shrine of art (an opera house or a museum). Would it not be better and truer to the values underlying many works of art, to strive throughout the course of one’s life, especially within the money-generating day-job, to make kindness, tenderness, sympathy and beauty more alive and real in the world?

Tantalisingly and tragically, the difference between beauty and ugliness, goodness and cruelty is in most enterprises a few percentage points of profit. Therefore, for the sake of just a tiny bit of surplus wealth, wealth that isn’t strictly even needed, human life is daily being degraded and sacrificed.

It would be more humane if rich business people agreed to sacrifice a little of their surplus wealth in their main area of activity and in the most vigorous period of their lives, in order to render the workplace more noble and humane – and then bothered less with dazzling displays of artistic philanthropy in their later decades?

What we’re asking for is enlightened investment where a lower return is sought on capital in the name of Kindness and Goodness. There would be less fancy art at the end of it, but the values within works of art would be far more widely spread across the earth. The true test is how much goodness is done in the process of accumulation.

Eleven: People should be rewarded really well and really reliably for doing good. Goodness is not its own reward

We live in a society in which – as is often lamented – money seems to be the overriding motive; children from the age of five say that their primary ambition is to be rich. Cynically one might say that everyone is corrupt. But one might point to a more generous explanation. In the absence of a better alternative money feels, to a lot of people, like the most reliable and most genuine reward, because maybe – at the moment – it is the most reliable reward.

Ironically, the one thing the hard-working rich don’t actually want and are not in any way motivated by is money itself. They have far more than enough of that already and they know it. Their every material need is catered for (one can nowadays buy a comfortable life for a year using what they earn in a day). Nor – at this point in the history of civilisation – are the rich likely to be working for the sake of their children. There are too many examples of large fortunes that have driven kids insane with guilt for any modern plutocrat to be able to tell themselves that they are doing it for the next generation.

The rich are not, therefore, working to make more money with an eye to spending it. They are making money in order to be liked. They are doing so for the sake of status, as a way of keeping score and letting the world know of their value as human beings. The rich work for love and for honour. They stay up late at the office out of vanity – because they want to be able to walk into rooms full of strangers and be swiftly recognised by those that matter – and deemed miraculous and clever for having made fortunes, whose size is carefully recorded by the media the world over.

Wise societies that have properly understood the psychology of the rich now have a trump card to play. As Adam Smith put it, “The great secret of education is to direct vanity to proper objects.” That is, we should target the vanity of the rich and encourage them to act well from that most powerful of desires: the desire to be loved. Our side of the deal will be to applaud very heartily when they behave well and to ensure we lavish upon them all the respect they so deeply crave. It will be a very small price to pay in return for the contentment of the planet.

Twelve: 80% of profit should come from the top 20% of our needs

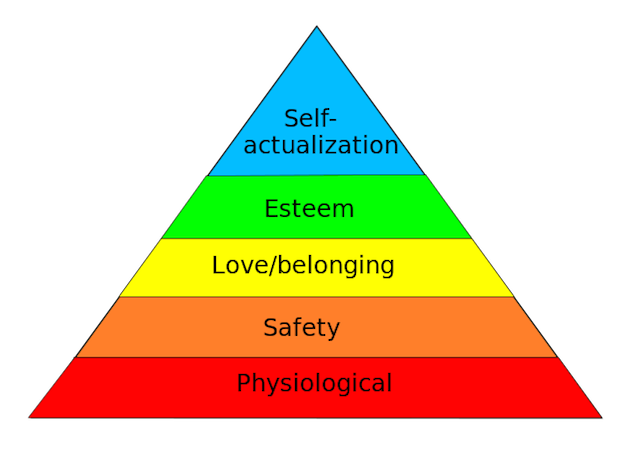

At present the overwhelming share of business activity is directed at meeting fairly basic needs: moving about, energy, food, shelter. That is, at present, Capitalism is mainly directed at the bottom layers of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

For most of history the economy of nations has almost exclusively been devoted to sheer physical survival, with only a tiny portion of human effort and resource going into higher needs. Mostly people were feeding themselves and making huts, with a very small surplus being directed to the more elaborate lives of the rich.

The distinction between higher and lower needs is something we understand in relation to our own lives. For instance, we know that maintaining a long-term relationship is both hugely important and at times extremely difficult. And we know that that’s a higher need than getting a new jumper. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with jumpers – only that their role in the big scheme of our lives should be minor.

We understand we have higher needs – for love, self-esteem, creativity, friendship and moral growth. But we don’t usually imagine commerce being able to help us. We have got a prejudice that paying for something can’t be connected to goodness. Though, in fact, there has long been an assumed link. The person who is offended by the idea of paying to address higher needs might have booked a trip to Florence or Bilbao to visit an art gallery or paid for a concert ticket, on the assumption that the art or the music will address their higher needs.

The fact is, commerce has only barely scratched the list of true needs. We need to live in beautiful cities, we need to have good advice and psychological support, we need to manage our emotions, we need to sustain strong families across generations, we need to cultivate our minds, we need to live in societies in which it is normal to be wise, kind, self-possessed. These are vast, immense undertakings and we have collectively a huge way to go. The fact that these ambitions don’t look the same as constructing highways of building pipelines doesn’t at all mean they are divorced from work, business or commerce. They are goods and services which have to be created by ingenuity, organisation and effort – in short, by work. And that work has to be remunerated. Far from worrying about what we might do when there is no more work, we should be preparing ourselves for almost endless labour to reach the true goal: widespread fulfilment.

***

It is entirely understandable that many people are disillusioned with capitalism. Because business as we currently know it is not as good as it should be. Our objection is not, in fact, to business as such but to business that is bad. The response is not, therefore, to wish that business would go away but to work to improve it so that it properly satisfies us as consumers and producers.