Work • Utopia

Why isn’t the Future here yet?

We used to believe that life would always go on more or less as it is. It might have been grim, but it had always been thus and would be so forever.

To be modern is, however, to know that – with time and a bit of luck – things will improve. And they will do so because of science, because clever people are eventually going to unpick all the problems that we can’t as yet master. That’s what a backwards glance at history from our vantage point proves unquestionably. With time, they sorted out tooth disease; they worked out how we could fly; they learnt how to conquer distance. And so we know – without a doubt – that other problems will also be solved. With time, we’ll learn how to live on different planets, grow a full head of hair, cure cancer, explain consciousness and figure out how to make energy at next to no cost. If we are in a fanciful speculative mood, we can go much much further: there will be a machine that will tell us who we should marry and how to read other people’s thoughts. There’ll be a way to determine what we are capable of and how we should therefore direct our careers. There’ll be a way to download all the world’s knowledge in minutes via a cable at the nape of the neck. And we’ll never have to die.

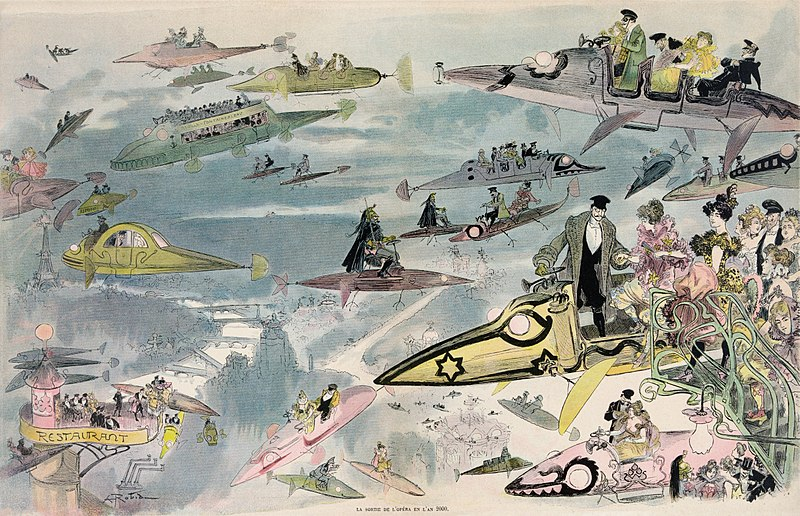

Back at the dawn of modernity, science fiction writers knew this way of projecting into the future. They pictured a world with submarines, mobile phones, space flight, mass prosperity and television. They were also particularly interested in flying cars.

Albert Robida, Coming out of the Opera in the year 2000, 1902.

We might chuckle at some of their ambitions, but to dream of future solutions is a natural state of mind in modernity – and not so foolish either. Most of our technological dreams will come true. The question, and it’s a very big and very painful question indeed, is when.

We may be advancing towards a better future, but we also have to recognise that we ourselves are stuck in what can generously be called a transitional period: the old cyclical world has been abandoned; the future is not yet here.

In the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana in Florence is one of the most poignantly honest maps ever made. The Salviati planisphere was drawn around 1525 by a civil servant in Seville. He had a good grasp of Europe, Africa and the Middle East but by the time he reached America, his knowledge was patchy in the extreme. He knew the rough outlines, but he didn’t know the topographical features or the names. He was stuck in a transitional phase of map making. One day it would be figured out: one day someone would reach the Pacific coast and send back precise information on the elevations of the Baja peninsula; one day a satellite would orbit the planet and send in microscopically precise information on every last square centimetre of the town of La Rinconada in the Peruvian Andes. But for now, in 1525, there was no option but to dwell in tantalising semi-ignorance.

Salviati world map of 1525

In so many areas of knowledge, we are like the Salviati map maker. Our understanding of the human brain is eerily akin to our grasp of the world in 1525. There are countries and coastlines that we have explored fairly well, zones of the occipital lobe and the postcentral gyrus that match our understanding of the Bavaria Alps or the Loire in the early sixteenth century – but other areas are as remote as Alaska and Chile once used to be.

When it comes to neuroscience, we are at the canoe building stage. We haven’t yet sent our first proper seaworthy vessel into the oceans. We can have fun daydreaming like Jules Verne but none of our most exciting projections spare us the deeper, more painful insight. If we are reading this today, it will all come too late for us.

There will eventually be fully completed maps of the mind, there will be ways of manipulating our neurology and optimising our intelligence; we will figure out why love is so difficult and how we should lead our lives; we’ll discover how to reverse cell damage and the best way to prevent the aging process. We’ll learn how not to have to die.

But it will be too late for us. We’ll be long gone. We’ll be like the unfortunates who died of measles before the vaccine was ready, who had a fatal crash before airbags, who had to do sums before calculators and who got shipwrecked on the Cape of Good Hope before Airbus. Others will feel as sorry for us as we feel for those medieval paupers who died in extraordinary agony of a disease that could now be vanquished with a pill worth $1 from the supermarket. Our present suffering will – in time – come to seem utterly avoidable – and in its way pitiful.

What modernity denies us is the comfort of knowing that what we’re suffering through is ‘necessary.’ It isn’t fundamentally, our species simply hasn’t had quite enough time to figure it out. It’s as necessary as toothache once was, that is, not very. We just haven’t done the sums and run the experiments yet. We can see what is coming but we also know – with sad certainty – that we won’t be around to enjoy it. We won’t be there for the plug-in education tools and the career guidance implants. We’ll miss the hair regrowth creams and the pills for eternal life. We’re in our own Middle Ages in multiple areas, except that, unlike those in agony in the 13th century who saw themselves as enduring a Biblical curse, we know we’re in a transitional period while we wait for the laboratories to build their prototypes. The particular agony of modernity is to see the shape of a better future, to understand that our pain isn’t fundamentally justified, to spy the rescue ship on the horizon – and yet to be sure that we will be dead by the time help arrives.