Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

Why We Need Moments of Mad Thinking

We banish a great many thoughts from our minds on the grounds that they are, as we put it, ‘mad’. Some of them evidently are: too mean, flawed, absurd or petty to deserve further exploration. But it’s one of the tragedies of our thinking lives that, amidst the detritus of dismissed thoughts, there are invariably a great many that could have been of high value, if only we had dared to examine them further, if only we hadn’t been so scared of their less conventional and more speculative dimensions, if only we hadn’t been so resistant to an occasional burst of ‘mad’ thinking.

Many of the greatest thoughts humanity has ever produced possess – at some level – an unusual and, from some angles, insane dimension. The masterpieces of art, the business plans of certain corporations, the conversations of inspired lovers, the visions of political theorists, all have elements of protest against the settled status quo, and contain aspects that are eccentric, contrary to received opinion and impatient with day-to-day practicalities – and yet that have for all this hugely benefited our species. Our thinking lives are grievously harmed by a background imperative to appear at all times wholly normal and entirely sane: we should, to maximise our insights, learn to make friends with moments of ‘mad’ thinking

A central step in ‘mad’ thinking is to temporarily set aside the normal (but not always wise) restrictions on our imaginations. For instance, money is naturally almost always a major consideration but in a spirit of ‘mad’ enquiry, we can ask ourselves how we’d approach an issue if money weren’t a factor. Maybe we’d suddenly see that a particular career deeply suited our nature, perhaps we’d concentrate far more on beauty or kindness, honesty or adventure, we might end up living in a completely different country or starting a new relationship. Without the inhibiting need to think only within the parameters of sensible financial planning, ideas that we usually censor might start to come to the fore, some of which could be highly valuable. Furthermore, it could turn out, on closer examination, that some of our desirable plans were not in fact entirely dependent on finances, it was simply that we had grown used to turning down every more ambitious idea on the grounds of money.

Similarly, around a career move we could ask ourselves, in a ‘mad’ spirit, what we’d do if we knew we couldn’t fail. Liberated not to think always of our laughing critics, we might discover that we’d very much like to pursue a business venture – if we it knew it would be solidly profitable after a few years; or perhaps we’d concentrate on sport – if we were guaranteed to reach a professional level. Or we might opt to spend more time looking after our children – if we knew this wouldn’t prevent advancement in our working life. Or we might spend our evenings writing a novel – if we could be sure that it would get published and sell a respectable number of copies. Of course, in reality there can’t be such guarantees but holding our fears aside for a certain amount of time helps us to identify our areas of real enthusiasm, longing and ambition that we would otherwise too soon push out of our minds.

More broadly, we can use ‘mad’ thinking to develop our social and political perspectives. We might ask, for instance what our concerns would be if we could be the absolute ruler of the world for a month. Maybe we’d take a great deal of interest in architecture or reinvent the school system. We might rethink how people get rewarded and whose face appears on magazines. We could redesign holiday resorts or re-engineer the way leaders are chosen. This ‘mad’ exercise helps us to recognise social and political ambitions that may have genuine merit. ‘Mad’ thinking is not, as we might first suppose, at odds with reality, it is an imaginative mechanism for revealing less obvious – but important – possibilities in the real world.

‘Mad’ thinking may not contain precise answers (how actually to remake the media or wean us off fossil fuels) but it encourages us in something that is logically prior to, and in its own way as important as, practical and technological mastery: the identification of a particular issue that we would like to see solved or that moves us. Changes in personal life and in society and business don’t in any case usually begin with practical steps: they start as acts of the imagination, with a sharpened sense of a need for something new, be this for an engine, a piece of legislation, a social movement or a new way to spend the weekend. The details of change may eventually get worked out, but the crystallisation of the wish for change has to take place at a prior stage, in the minds of people who are free enough to envisage what doesn’t yet exist and isn’t as yet wholly reasonable.

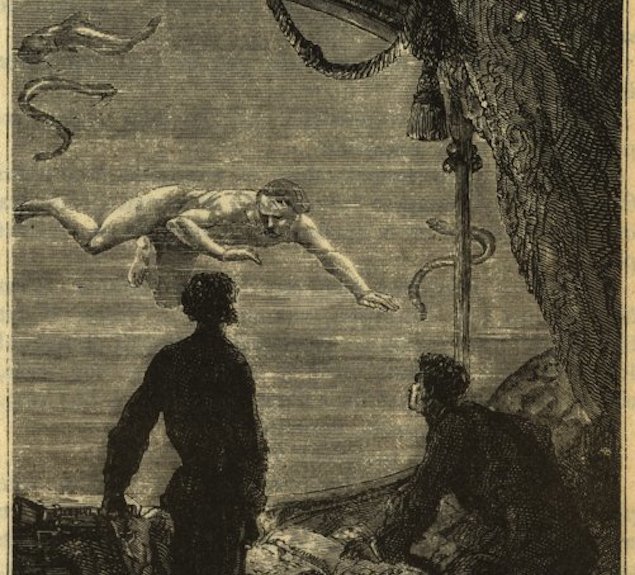

One of the world’s most inspiringly ‘mad’ thinkers was the French nineteenth-century writer Jules Verne. In a series of novels and stories, he had the most unlikely thoughts about how we might live in the future. In 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, published in Paris in 1870, Verne narrated the adventures of the Nautilus, a large submarine that tours the world’s oceans often at great depth (the 20,000 leagues – about 80,000 kilometres – refer to the distance travelled). When writing the story, Verne didn’t worry too much about solving every technical issue involved with undersea exploration: he was intent on pinning down capacities he felt it would one day be important to have. He described the Nautilus as being equipped with a huge widow even though he himself had no idea how to make glass that could withstand immense barometric pressures. He imagined the vessel having a machine that could make seawater potable, though the science behind desalination was extremely primitive at the time. And he described the Nautilus as powered by batteries – even though this technology was in its infancy.

‘Wouldn’t glass shatter at that pressure?’ Keeping certain questions at bay for long enough to shape a vision. Original illustrations by Alphonse de Neuville and Edouard Riou.

Jules Verne wasn’t an enemy of technology; he was deeply fascinated by practical problems. But, in writing his novels, he held off from worrying too much about the details to the ‘how’ questions. He wanted to picture the way things could be, while warding off – for a time – the many practical objections that would one day have to be addressed. Verne was thereby able to bring the idea of the submarine into the minds of millions while the technology slowly emerged that would allow the reality to take hold. Eventually, we always need to work out answers to ‘how’ questions, but ‘mad’ thinking reminds us of the significance, dignity and legitimacy of starting with our intentions.

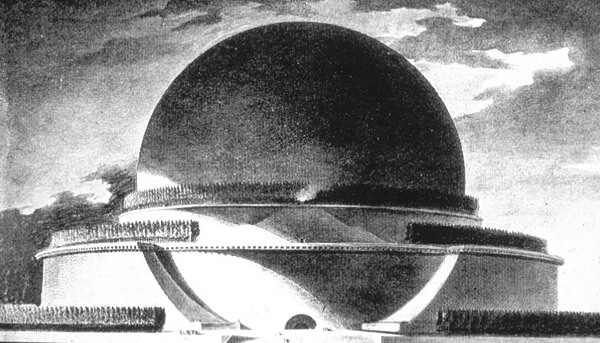

In his earlier story of 1865, From the Earth to the Moon, Verne had explored the notion of orbiting and then landing on the moon. He let himself imagine such a feat without getting embarrassed that it was entirely beyond the reach of all available technology.

It could become real in part because it had first been imagined. Illustrations by Henri de Montaut for the original edition.

Verne imagined that the United States would launch a mission to the moon from a base in southern Florida. He fantasised that the craft would be made of the lightest metal he knew (aluminium). He assigned what seemed an unspeakably large price tag to the venture; the equivalent of more than the entire GDP of France at the time – which turned out to be a very respectable guess at how much the Apollo programme would cost. It was a truly prescient imaginative description. His vastly popular book may not directly have helped any engineer, but it did something that in the long run was perhaps equally important to the mission: it fostered an aspiration. It explains why NASA named a large crater on the far side of the moon after Verne in 1961, and the European Space Agency followed suit with the launch of the Jules Vernes 2008, a rocket which travelled to the International Space Station carrying the original frontispiece of the 1872 edition of From the Earth to the Moon in its cargo bay.

The projectile, as pictured in an engraving from the 1872 Illustrated Edition.

Asking oneself what a better version of our lives might be like, without direct tools for a fix to hand, can feel highly immature and naive. Yet, it’s by formulating visions of the future that we more clearly start to define what might be wrong with what we have – and start to set the wheels of change in motion. Through ‘mad’ experiments of the mind, we get into the habit of counteracting our detrimental tendencies to inhibiting our thinking around wished-for scenarios that seem (in gloomy present moments at least) deeply unlikely. Yet such experiments are in truth often deeply relevant, because when we look back in history we can see that so many machines, projects and ways of life that once appeared extremely utopian have come to pass. Not least, Captain Kirk’s phone.

The ‘Communicator’ from 1966

We all have a ‘mad’ side to our brains, which we are normally careful to disguise, for fear of humiliation. Yet the road to many good ideas, precise insights and valuable suggestions has to pass through a few rather outrageous or ridiculous-seeming early notions. If we feel too much disgust or fear as our minds throw up their wilder suggestions, we will stop the thinking process too early – and won’t have given some of our best thoughts the chance they sometimes desperately need.

Manoeuvre:

In the privacy of the mind, allow yourself time for some ‘mad’ thinking.

What is the biggest version of your current ambitions?

If you could not fail, what would you do?

If others would not ever laugh, what would you do?

If there were no financial pressures, how would you approach things?

If you could be the absolute ruler for a while, how would you reform the world?

Without thinking too much, complete the sentence: If you didn’t have to be sensible, I would….

Describe your ideal country: what would the houses be like? What would the ideal corporation do? How would people have relationships? What technologies would they have?

Select a few bits of this madness – and make it your goal.