Work • Utopia

The Importance of Utopian Thinking

To be accused of ‘utopian thinking’ is a particular insult in our times. We pride ourselves on being grounded, realistic and sober.

Insofar as we dare to imagine the future, we do so with one peculiar tic: we cautiously ask ourselves what the future will be like on the basis of current trends; we almost never ask the one big philosophically-minded question: what should the future be like? We proceed as humble futurologists, viewing the future as something to be deduced, rather than as bolder and more directive philosophers, viewing the future as something to be imagined – and thereby in part, summoned into being.

To think in a utopian way is a prime political act. It involves a refusal to be limited by our current obsession with the here and now in order to focus on the world as it could and should be in order to maximise human flourishing.

The most famous utopia ever produced in the West was Plato’s Republic, written in Athens around 380 BC. The work lays out how the society of the future should be arranged: with definitions of the ideal system of child-rearing, diet, education, law and government. This tradition of utopian writing deserves a renaissance.

In our day, much utopian thinking has gone into science fiction writing. This is one of the least prestigious of the literary arts, frequently dismissed as a subgenre consumed primarily by young men obsessed by the goriest or oddest possibilities for the future of our species.

Yet science fiction is in reality a much underestimated tool, for in its utopian, as opposed to dystopian, versions, it invites us imaginatively to explore what we want the future to be like – a little ahead of our practical abilities to mould it as we would wish.

Science fiction may not contain precise answers (how actually to make a jetpack or a robot that loves us) but it encourages us in something that is logically prior to, and in its own way as important as, technological mastery: the identification of a particular issue that we would like to see solved. Changes in society seldom begin with actual inventions. They begin with acts of the imagination, with a sharpened sense of a need for something new, be this for an engine, a piece of legislation, an idea of how people should marry or a social movement. The details of change may eventually get worked out in laboratories, committee rooms and parliaments, but the crystallisation of the wish for change takes place at a prior stage, in the imaginations of people who know how to envisage what doesn’t yet exist.

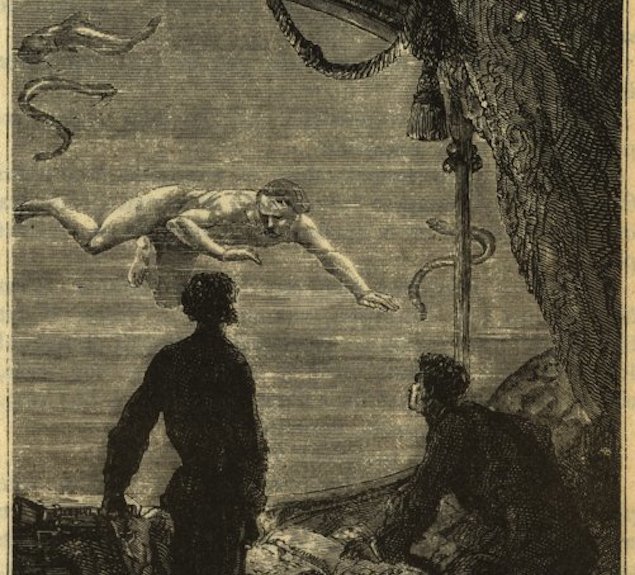

In 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, published in Paris in 1870, Jules Verne narrated the adventures of the Nautilus, a large submarine that tours the world’s oceans often at great depth (the 20,000 leagues – about 80,000 kilometres – refer to the distance travelled). When writing the story, Verne didn’t worry too much about solving every technical issue involved with undersea exploration: he was intent on pinning down capacities he felt it would one day be important to have. He described the Nautilus as being equipped with a huge widow even though he himself had no idea how to make glass that could withstand immense barometric pressures. He imagined the vessel having a machine that could make seawater potable, though the science behind desalination was extremely primitive at the time. And he described the Nautilus as powered by batteries – even though this technology was in its infancy.

‘Wouldn’t glass shatter at that pressure?’ Keeping certain questions at bay for long enough to shape a vision. Original illustrations by Alphonse de Neuville and Edouard Riou.

Jules Verne wasn’t an enemy of technology. He was deeply fascinated by practical problems. But in writing his novels, he held off from worrying too much about the ‘how’ questions. He wanted to picture the way things could be, while warding off – for a time – the many practical objections that would one day have to be addressed. He was thereby able to bring the idea of the submarine into the minds of millions while the technology slowly emerged that would allow the reality to take hold.

In his earlier story of 1865, From the Earth to the Moon, Verne had explored the notion of orbiting and then landing on the moon. He let himself imagine such a feat without getting embarrassed that it was entirely beyond the reach of all available technology.

It could become real in part because it had first been imagined. Illustrations by Henri de Montaut for the original edition.

Verne imagined that the United States would launch a mission to the moon from a base in southern Florida. He fantasised that the craft would be made of the lightest metal he knew (aluminium). He assigned what seemed an unspeakably large price tag to the venture; the equivalent of more than the entire GDP of France at the time – which turned out to be a very respectable guess at how much the Apollo programme would cost. It was a truly prescient imaginative description. His vastly popular book may not directly have helped any engineer, but it did something that in the long run was perhaps equally important to the mission: it fostered an aspiration. It explains why NASA named a large crater on the far side of the moon after Verne in 1961, and the European Space Agency followed suit with the launch of the Jules Vernes 2008, a rocket that travelled to the International Space Station carrying the original frontispiece of the 1872 edition of From the earth to the Moon in its cargo bay.

The projectile, as pictured in an engraving from the 1872 Illustrated Edition.

The key mental move in science fiction – ‘what would we want life to be like one day?’ – has traditionally been focused on technology. And yet there is no reason why we would not perform equally dramatic thought-experiments in quite different fields, in relation to family life, relationships – or capitalism itself. That is the task of philosophical utopian thinking.

Asking oneself what a better version of something might be like, without direct tools for a fix to hand, can feel immature and naive. Yet it’s by formulating visions of the future, that we more clearly start to define what might be wrong with what we have – and start to set the wheels of change in motion. Through utopian philosophical experiments, we get into the habit of counteracting detrimental tendencies to inhibit our thinking around wished-for scenarios that seem (in gloomy present moments at least) deeply unlikely. Yet such experiments are in truth often deeply relevant, because when we look back in history we can see that so many machines, projects and ways of life that once appeared simply utopian have come to pass. Not least, Captain Kirk’s phone.

The Communicator, from 1966

We all have a utopian side to our brains, which we are normally careful to disguise, for fear of humiliation. Yet, our visions are what carve out the space in which later patient and real development can occur.

The School of Life is committed to Utopian Thinking and the envisaging of the world as it should be.