Leisure • Western Philosophy

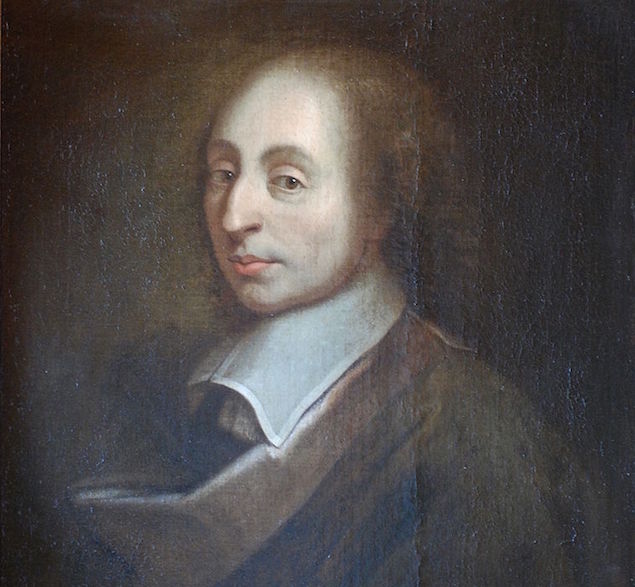

Blaise Pascal

It is still, tragically, sometimes assumed that the best way to cheer someone up is to tell them that everything will turn out all right; to intimate that life is essentially a pleasant process in which happiness is no mirage and human fulfilment a real possibility.

However, we need only read a few pages of the book known as the Pensées by the great French 17th-century philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623-62) to appreciate how entirely misguided this approach must be, because Pascal pulls off the feat of being both one of the most pessimistic figures in Western thought and simultaneously one of the most cheering. The combination seems typical: the darkest thinkers are, paradoxically, almost always the ones who can lift our mood.

Pascal was born in Auvergne in central France in June 1623, and from the earliest days, learnt to look at the glass of life as half-empty. His mother died when he was three, he had few friends, he was a hunchback and he was always ill. Luckily, he was recognised from an early age – and by more than just his proud family – to be a genius. By twelve, he had worked out the first thirty-two propositions of Euclid, he went on to invent the mathematics of probability, he measured atmospheric pressure, constructed a calculating machine and designed Paris’s first omnibus.

Then, at the age of thirty-six, ill-health forced him to set aside plans for further scientific exploration and led him to write a brilliant, intensely pessimistic series of aphorisms in defence of Christian belief which became known as the Pensées – the book for which we today chiefly remember and revere him.

The purpose of the work was to convert readers to God and Pascal felt the best way to do this was to evoke everything that was terrible about life. Having fully considered the misery of the human condition, he assumed his readers would instantly turn for salvation to the Catholic Church. Unfortunately for Pascal, very few modern readers now follow the Pensées like this. The first part of the book, listing what is wrong with life, has always proved far more popular than the second, which suggests what is right with God.

Pascal begins by telling us that earthly happiness is an illusion – but is especially keen to point out how much we hate being on our own, thinking and exploring our lives. He is perhaps best known of all for this aphorism of genius:

Tout le malheur des hommes vient d’une seule chose, qui est de ne savoir pas demeurer en repos, dans une chambre.

All of man’s unhappiness comes from his inability to stay peacefully alone in his room.

The aphorism should be written in large letters in the departure lounges of all the world’s airports.

Pascal’s charm lies in his bitterness and tart cynicism. People will do anything rather than consider their dreadful reality. “Man is so vain that…the slightest thing, like pushing a ball with a billiard cue, is enough to divert him.” At the same time, they are tortured by their passions, especially the passion for fame; “We are so presumptuous that we want to be known all over the world, even by people who will only come after we have gone.” And perhaps the greatest source of suffering is the most banal – boredom. “We struggle against obstacles, but once they are overcome, rest proves intolerable because of the boredom it produces.” Pascal’s conclusion: “What is man? A nothing compared to the infinite.”

Pascal misses no opportunities to confront his readers with evidence of mankind’s resolutely deviant, pitiful and unworthy nature. In seductive classical French, he informs us that happiness is an illusion (‘Anyone who does not see the vanity of the world is very vain himself’), that misery is the norm (‘If our condition were truly happy we should not need to divert ourselves from thinking about it’), that true love is a chimera (‘How hollow and foul is the heart of man’), that we are as thin skinned as we are vain (‘A trifle consoles us because a trifle upsets us’), that even the strongest among us are rendered helpless by the countless diseases to which we are vulnerable (‘Flies are so mighty that they can paralyse our minds and eat up our bodies’), that all worldly institutions are corrupt (‘Nothing is surer than that people will be weak’) and that we are absurdly prone to overestimate our own importance (‘How many kingdoms know nothing of us!’). The very best we may hope to do in these circumstances, he suggests, is to face the desperate facts of our situation head on: ‘Man’s greatness comes from knowing he is wretched’.

Given the tone, it comes as something of a surprise to discover that reading Pascal is not at all the depressing experience one might have presumed. The work is consoling, heartwarming and even, at times, hilarious. For those teetering on the verge of despair, there can paradoxically be no finer book to turn to than one which seeks to grind man’s every last hope into the dust. The Pensées, far more than any saccharine volume touting inner beauty, positive thinking or the realisation of hidden potential, has the power to coax the suicidal off the ledge of a high parapet.

If Pascal’s pessimism can effectively console us, it may be because we are usually cast into gloom not so much by negativity as by hope. It is hope – with regard to our careers, our love lives, our children, our politicians and our planet – that is primarily to blame for angering and embittering us. The incompatibility between the grandeur of our aspirations and the mean reality of our condition generates the violent disappointments which rack our days and etch themselves in lines of acrimony across our faces.

Hence the relief, which can explode into bursts of laughter, when we finally come across an author generous enough to confirm that our very worst insights, far from being unique and shameful, are part of the common, inevitable reality of mankind. Our dread that we might be the only ones to feel anxious, bored, jealous, cruel, perverse and narcissistic turns out to be gloriously unfounded, opening up unexpected opportunities for communion around our dark realities.

We should honour Pascal, and the long line of Christian pessimists to which he belongs, for doing us the incalculably great favour of publicly and elegantly rehearsing the facts of our sinful and pitiful state. Reading Pascal reminds us that the secular are at this moment in history a great deal more optimistic than the religious – something of an irony, given the frequency with which the latter have been derided by the former for their apparent naiveté and credulousness. It is the secular whose longing for perfection has grown so intense as to lead them to imagine that paradise might be realised on this earth after just a few more years of financial growth and medical research. With no evident awareness of the contradiction they may, in the same breath, gruffly dismiss a belief in angels while sincerely trusting that the combined powers of the IMF, the medical research establishment, Silicon Valley and democratic politics will together cure the ills of mankind.

Religions have wisely insisted that we are inherently flawed creatures: incapable of lasting happiness, beset by troubling sexual desires, obsessed by status, vulnerable to appalling accidents and always slowly dying.

Why should any of this be so cheering? Perhaps because pessimistic exaggeration is so comforting. Whatever our private disappointments, we can start to feel very fortunate when we compare our mood to Pascal’s. Pascal wanted to turn us to God by telling us how awful life was. But by sharing his troubles, he ironically strengthens us to face the troubles of our own lives on this earth with greater courage and forbearance.