Relationships • Dating

Dating When You’ve Had a Bad Childhood

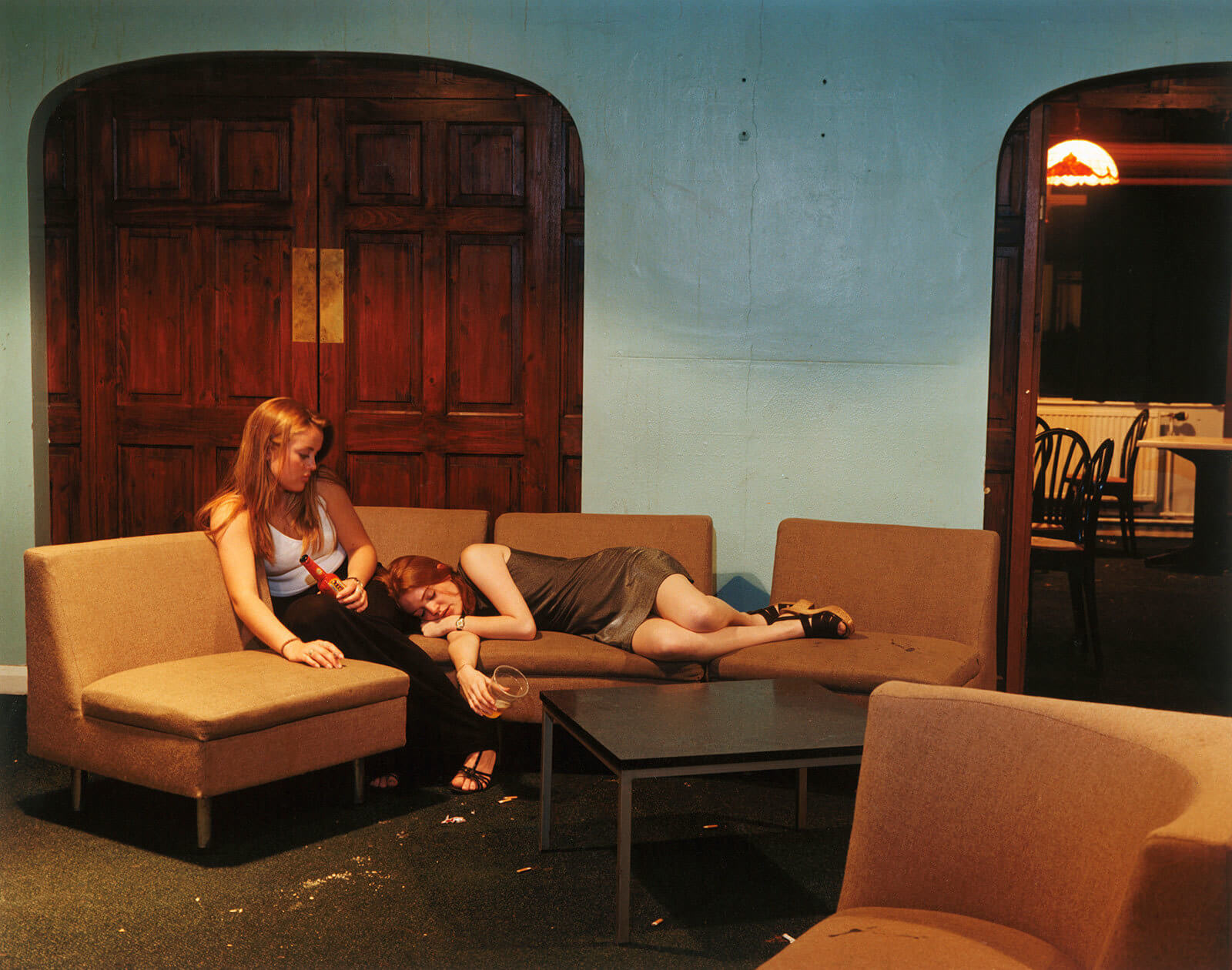

In the course of any adult life, there will be periods when we’ll end up involved in that slightly odd, slightly unrepresentative and invariably slightly challenging activity: looking. Most people around us won’t be any the wiser, but with greater or lesser subtlety, we will be scanning: suggesting coffees and lunches, accepting every invitation, giving out our email addresses and thinking with unusual care about where to sit on train journeys. Sometimes the rigmarole will be joyful; at times, a bore. But for a portion of us, as many as one in four, it will count as one of the hardest things we ever have to do. Fun won’t remotely come into it. This will be closer to trauma. And it will be so for a reason that can feel more humiliating still: because, a long time ago now, we had a very bad childhood – one whose impact and legacy we still haven’t yet wholly mastered.

It may not look like it, but babies are also looking out for love. They’re not going out in party smocks or slipping strangers’ their phone numbers. They are lying more or less immobile in cribs and are capable of little besides the occasional devastating cute smile. But they too are looking out for someone’s arms to feel safe in; for someone who can soothe them, someone who can stroke their head, tell them it will all be OK when things feel desperate and lend them a breast to suck on. They are looking – as the psychologists call it – to get attached.

But unfortunately, for one in four of us, the process goes spectacularly wrong. There is no one on hand to care properly. The crying goes unheeded, the hunger unassuaged. No one smiles reliably or cuddles confidently. There is no welcoming breast. In the eyes of the care-giver, there is depression or anger where there should have been delight and reassurance. And as a result, a fear of existence takes hold for the long term – and dating becomes a very hard business indeed.

For those of us who experienced early let downs, there is simply little in us that can ever believe that a search for love will go well – and we will therefore bring an unholy commitment to bear on ensuring that it doesn’t. The dating game becomes the royal occasion when we can confirm our deepest suspicion: that we are unworthy of love.

We may, for example, fixate on a candidate who is – to more attuned eyes – obviously not interested; their coldness and indifference, their married-status or incompatible background or age, far from putting us off, will be precisely what feels familiar, necessary and sexually thrilling. This is what is meant to happen when we love: it should hurt atrociously and go nowhere.

Or, in the presence of a potentially kind-hearted and available candidate, we may become so demanding and uncontained, so unreasonable and urgent in our requests, that no sane soul would remain in contention. We will spoil any potentially good impression by bringing a lifetime of self-doubt and loneliness onto the shoulders of an innocent stranger.

Alternatively, unable to tolerate the appalling anxiety of not yet quite knowing where we stand, we may decide to settle the matter by ourselves, preferring to crash the plane than see how it might land. We’ll interpret every ambiguous moment negatively, for sadness is so much easier to bear than hope: the slightly late reply must mean that they have found somebody else. Their busy-ness must be a disguise for sudden hatred. The missing x at the end of their message is conclusive evidence that they have seen through our sham facade. To master the terror of another letdown, we go cold, we respond sarcastically to sincere compliments and insist with aggression that they don’t really care for us at all, thereby ensuring that they eventually won’t.

To escape these debilitating cycles, we need to accept that we’re searching for someone to love us while wrestling with the most fateful of background suspicions: that we don’t in any way deserve love.

It’s only by properly mastering what once happened to us, the letdown we first experienced as infants, that we can start to separate out past trauma from present reality – and therefore learn to navigate the ambiguities and occasional risks of adult dating. It isn’t that we have been told that we don’t deserve to exist; they’re just busy tonight. They don’t loathe us, they’re married to someone else, as lots of people (who we carefully have chosen not to look at) happen not to be. They’re not peculiar, it’s just unfair and overwhelming to ask someone you’ve known for twelve hours to make up for a lifetime of loneliness.

We need to see that this is not the first time we have been ‘dating’. We have done it before long ago and it was the ways in which it went very wrong that holds the key to our adult errors – our intensity, our coldness and our lack of judgement. The catastrophe we fear will happen has already happened. The challenges we set up for ourselves are attempts to get back in touch with a trauma we haven’t either understood or mourned.

We can in time learn to ask people on a date because we grasp that we’re not thereby asking them what we think we’re asking: do I deserve to exist? We’re asking something far more innocent, and far more survivable were the answer to be negative: might you be free on Friday? And we can survive because, even though we once got terribly hurt in the nursery, we are now that most resilient of things: an adult. So we have many other options, we won’t (as we once feared) die of loneliness if it doesn’t work. We can take our time, we can allow things to emerge, we can tolerate ambiguity. And with such security in mind, we can begin to do that most momentous of things: without risking our sanity, see if someone we like might – after all -want to go out tonight.