Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

On Exercising the Mind

In general, we are very much alive to the benefits of exercise. And not only around physical fitness. In learning to speak another language, drive a car or play an instrument, we recognise the value of going over things again and again, of rehearsing, memorising and testing according to established principles. We willingly follow the advice of the tennis coach to take the ball a fraction earlier on the backhand or to overcome a tendency to maintain too upright a posture going into the shot. Ultimately what we are trying to do is to form good habits so that, with sufficient practice, we won’t have to think (for example) about how to reverse the car into a parking bay or return the ball from the left hand corner. It will simply be easy and natural.

However, for major cultural reasons, we are extremely selective in our enthusiasm for areas where we accept the utility of practice, teaching, systematic education, rehearsal and repetition.

Very strangely and sadly, exercise has come to feel alien in the area of our intimate emotional and cultural lives. Jane Austen – for instance – would have readily accepted that people have to learn how to have conversations, that there are rules to be practiced in relationships, and that compassion is something that can be learnt. She spoke movingly about what she termed ‘the training of the heart’. But we have subsequently developed a highly negative take on the role of teaching, rules and exercises in emotional, social and cultural life. It has come to seem as if rules will always be oppressive. The idea of learning how to have a relationship, be a friend or have a conversation now sounds unbearably stiff, too formal, pompous or just fake. So, today we train the cook, but leave the lover alone.

Here, we accept there are rules…

People like to say that there are, at heart, no rules about conversation, bringing up a family or identifying a purpose to one’s life. There’s now a widespread dislike of generalisations and an assumption that no one knows the secrets of living well; we must simply make up the rules as best we can, there is no accumulated wisdom we can draw from. It’s about starting from scratch every time and cobbling together the answers through painful experiences, one mistake after another. Many influential 20th-century intellectual figures (Virginia Woolf, DH Lawrence, Sartre to start the list) were supporters of such spontaneity, naturalness and authenticity – and equal opponents of anything that looked like an ‘answer’ derived from Other People.

At one point, rules really did look like the problem

Their praise of spontaneity was, at a certain point, very liberating and necessary. It was a plausible reaction to rigid, unimaginative and conformist societies – who in many areas followed extremely deficient rules. But our assumptions about training and exercise have stuck around even as the external environment has changed. Gradually, in part thanks to their influence, our society now is anything but oppressive or dogmatic.

We are now more likely to suffer from a very different set of troubles. We feel chaotic – overwhelmed by our own appetites, very unsure about what we should do with our lives, fearful of wasting opportunities and afraid we won’t accomplish anything, paralysed at times by unstructured freedom.

This is therefore a highly relevant moment to reconnect with the Ancient Greek idea that living well is crucially dependent upon education: upon learning emotional skills and good habits. This particular era of history seems ready for the founding insight of Greek philosophy: that the good life is something that can be taught.

Across large swathes of existence (relationships, travel, family life, work, ambition, anxiety, attitudes to money …) there are things we can learn how to do more reliably. There are training exercises which can significantly improve how well parts of our lives will go.

This training falls into two big kinds: Exercises of Clarification and Exercises of Reinforcement:

Exercises of Clarification

Many of our troubling experiences, as well as many hopeful ones, are cloudy and vague – even if they are strongly felt. Who do I envy? What career really excites me? What am I annoyed or anxious about? These are questions we don’t automatically know the answer to and can often get confused about (we shout at the wrong person, take the wrong job, miss opportunities…). Our instincts in these areas are hugely consequential for our lives – and the lives of those closest to us – and yet instinct will not be enough.

An exercise in clarification is the deliberate practice of asking yourself searching questions about instincts and of getting into the habit of trying to answer them properly.

For instance, one may frequently feel upset or frustrated in a relationship – yet also hopeful that things can go better. It might help to have these systematic questions to hand:

What do I most resent about my partner? Have I tried to explain this properly to them (rather than complaining bitterly or remaining silent)?

How would you like to be a better person in this relationship?

What would you like to apologise about to your partner?

The emphasis is on clarification: bringing into focus half-formed thoughts, more closely defining suspicions, hopes and anxieties. In most cases, you know the answers already, sort of. But the answers are out of focus – and this is the fatal problem that proper mental exercise is designed to help us overcome.

Exercises of Reinforcement

There’s a second species of exercise. Often enough our troubles cannot really be blamed on ignorance. We know what we should do. Only we don’t do it. Classically, this is the problem known by the Ancient Greeks as ‘akrasia’ – or ‘weakness of will’. We go wrong not so much because we don’t know, but because we lack the motivation to act on our best insights. So we need constant help in bolstering and reinforcing the wiser moments.

There are numerous tactics for providing this assistance. For a start, it helps to hear another person say what we already kind of know; it gives the belief extra weight. It enhances our trust and makes us feel a little less alone. We aren’t looking for revelation, we’re looking for corroboration.

Also, hearing truths put in elegant language or images is beneficial. Wisdom sticks better in the mind when conveyed with the sensuous force of art – in a picture, a song or a poem. For example, Buddhist thought stresses our need to build up resilience to difficult events. But it does so not only through lectures or intellectual arguments, in some of its denominations, it asks us to meditate on beautiful images of bamboo trees (some of the thinnest, strongest plants on the planet), to strengthen our sense of how we should be ready to meet with the tempests of our own lives.

We also need big truths to be repeated to us. Once won’t be enough. Religions understood this. We might not agree with the messages they were trying to transmit. But they usefully pictured the mind like a bucket with holes in it. It can carry water, but only a short distance. Soon it has all leaked away. The insight that fired you up at 7.00pm – when you were driving home and the last rays of sunlight were falling across the trees of a suburban park and you felt a deep gratitude for existence and a longing to be more patient with your partner – will have vanished by 11.00pm. We need to keep going back and recovering the good ideas that are lost at every hour.

Now we need one for the mind

We accept the need to exercise our bodies so as to get fit, but currently we are suspicious of any attempt to exercise the mind – in order to attempt to be wise.

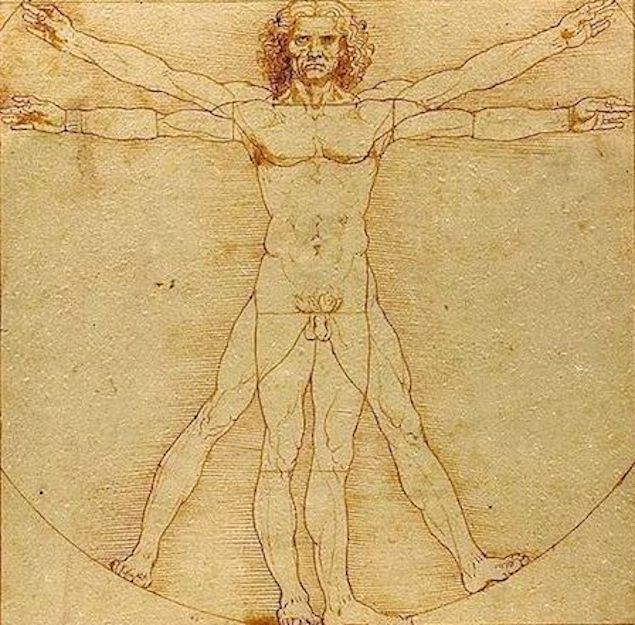

The first thing we do in a gym is make diagnoses: we go to a different area to work on a different part of ourselves. This would be similar to what should happen in an ideal Philosophers’ Gym of the future. Instead of thinking that we need to work on our biceps, we might decide we need to work on our envy or on our confidence, our frustration or our capacities for gratitude.

Around current gyms, we understand the role of routine: we need to do the same thing many times to get results. We have developed some rather odd-looking but specially evolved exercise machines: various barbells, a contraption so you can flex your lower back muscles, routines with the exercise ball and so on… In the realm of the psyche there may be similar sets of odd-looking exercises, which we haven’t yet quite invented. There may be works of art you have to look at in certain ways, questions you have to ask yourself, texts to memorise, or situations to rehearse (being patient at the moment when you are irked; noting when you get defensive…).

In an ideal Philosophers’ Gym, we might walk into a room of people being tested in mock frustrating conversations, or rehearsing moments to step down during domestic rows. In a side room, we might find people analysing recent instances of particularly stubborn anxieties or breaking down hopeful fantasies into realistic plans.

It seems a folly to abandon our inner lives to individual initiative alone. All education is based on the idea of saving people time by transmitting the best that people who came before them have said and thought. We readily accept the need to train in physics, molecular biology, cooking and advanced aeronautics: we don’t insist on stumbling our way to plausible answers on how to land a plane or operate on the frontal cortex. We should therefore cease the folly of not offering people systematic help with the no less important challenges of Relationships, Careers, Children, Friends, Meaning, Loving and Dying.

The Philosophers’ Gym

We suggest three initial exercises to start: