Work • Business Skills

How Not to Let Work Explode Your Life

It’s 4.30pm, Thursday. The plane is still on the tarmac at Milan-Linate awaiting take off for the flight to Heathrow. Ellie makes herself open her laptop. Out of the window: the tail of an Airbus A320 shimmers in the afternoon light; a dark band of distant trees. The Tate and Lyle Environmental Compliance briefing document is going to need a lot of revision, after the discussions about the Brindisi plant. She drinks some mineral water. There’s another early start again in the morning. The person in the seat in front (just visible through the gap) is flicking through a magazine, licking their middle finger before turning a page. There are three emails about the Rotterdam contract and photos from her sister’s birthday dinner party last night, which she missed by about 939 miles.

The cabin steward offers a newspaper – she hasn’t time for it really, just for the Guardian headlines: the Mexican economy has failed to meet growth expectations, rape allegations are up in England and Wales; land disputes are triggering cast violence in India. A message from her partner: hey, did you make that change to the household insurance cover? No, not yet! (And can’t you stop fucking bugging me even when I’m on the plane!) The safety announcement starts. A guy Ellie was at college with got involved in property development, someone was saying he’s got his own plane. At college she did a course on the Greeks and Romans, she hasn’t thought about the big sweep of history for ages. Why did her relationship with X run into the sand four years ago? Are these costing estimates right? She hasn’t had a moment to herself since she stepped out of the shower at 6.17am this morning. Since then, it’s been constant business.

It’s one of the many points where we feel: work has taken over. Things I’d like to be properly engaged with – including: my sister, pondering what I’m doing with my life, nature, reading novels – have been squeezed to the edges. Bluntly: work has ruined my life. It threatens my sanity, my relationships and my health.

Normally, we’d be expected to be a bit shamefaced at this point. Cracking up isn’t an acceptable thing to do. There’s a risk of sounding whiney, self-pitying or just a bit of a loser – not able to take the heat. We’re haunted by the idea that we should be able to juggle everything, with poise and good humour. Our imaginations are haunted by the image of more competent types, perhaps Larry Page.

© Joi Ito/Wikipedia

Our own less satisfactory life must be due to our own failings. If we were cleverer, more efficient, more emotionally mature, more self-controlled … then everything would fall into place.

HOW WORK THREATENS SANITY

Personal troubles sometimes have big historical causes

In our own lives, we typically see problems close up. There are lots of details that are getting us down. There’s too much to do. You fly off the handle over little things. You worry about affording a house. Your partner is too demanding. You’re not sleeping very well. You might wonder what it is all for, but there isn’t much time to wonder these days. You feel guilty about not getting proper exercise.

We encounter the symptoms. But it’s hard for us to see if there’s a powerful causal factor that lies behind these localised frustrations and annoyances.

We understand this distinction between symptoms and causes in medical situations: someone might have a pain in their big toe and dry peeling skin. The natural instinct is to think: there’s something very wrong with my toe, because that’s where the pain is occurring. But the problem isn’t caused there. There’s something wrong with their kidneys leading to a buildup of urate crystals in the toe joint.

In the 1960s, feminism took off by making this same move: finding a big, underlying factor that explained a lot of personal gripes and annoyances. In the late 1950s, women across the US might think things like: my husband is a bit selfish; I wish I could have an interesting job and make decent money myself; I was a fool I should have worked harder at college, but I didn’t see the point at the time; I’m not even sure I want children – does that mean there’s something wrong with me? I feel frustrated every day.

In 1963, Betty Friedan argued that all of these complaints – which could seem like merely individual personal grievances – were in fact symptoms of a bigger issue which up to this point people hadn’t identified: it was, in her words, “the problem that has no name.”

“The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning [that is, a longing] that women suffered in the middle of the 20th century in the United States. Each suburban housewife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries … she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question — ‘Is this all?'”

Betty Friedan: it’s not you

Betty Friedan reframed the issue: what’s going on isn’t really just a local difficulty with your life. It’s not something specific about your particular relationship or your career options. You are suffering from a big historical problem. And she gave it a name: Patriarchy. She was pointing out that women were feeling the effects of living in a society that had evolved to focus on male authority and opportunity. Women were being given access to a really big story about the origins of their sufferings (big and small).

We believe that the suffering of the lawyer on the plane (in whose troubles we all share to a greater or lesser extent) should also be attributed to a large historical cause.

In this case, the problem lies with: Modernism.

Modernism

Modernism is the name of a phenomenon that captivated artists and writers from the middle of the 19th century. Starting in Paris and spreading to Vienna, London and New York, architects, poets, painters and novelists started responding to the vast expansion of cities, the arrival of the railways, the huge increase in newspapers and the amount of advertising that was going on all around them.

But, in its more ambitious forms, Modernism didn’t just reflect a new subject matter: painting busy streets rather than scenes from the bible or ancient history. Avant-garde artists started developing new styles – they changed the way they painted.

They went from highly-esteemed traditional works, like those of Claude Lorraine, that emphasised harmony and balance

To things like Georges Braque’s 1913 Cubist still life: Fruit Dish, Ace of Clubs.

Braque and his colleague Picasso were in the process of inventing Cubism. Cubist works struck early viewers as hard to understand, as too busy and broken up. But Braque and Picasso weren’t setting out to annoy people. They were signalling that something very important was happening, that life was getting more agitated, more fragmented, more sharp-edged. They started making images that reflected just these qualities.

Similar changes were taking place at the same time in literature. Traditional narrative was leisurely and clear. A very successful traditional novelist like Anthony Trollope would take care to let the reader know about what was happening. Reading a Trollope novel would be a calm, comfortable experience; maybe very slightly tedious, but definitely reassuring.

“Mr. Wharton was and had for a great many years been a barrister practising in the Equity Courts,—or rather in one Equity Court, for throughout a life’s work now extending to nearly fifty years, he had hardly ever gone out of the single Vice-Chancellor’s Court which was much better known by Mr. Wharton’s name than by that of the less eminent judge who now sat there. His had been a very peculiar, a very toilsome, but yet probably a very satisfactory life. He had begun his practice early, and had worked in a stuff gown till he was nearly sixty. At that time he had amassed a large fortune, mainly from his profession, but partly also by the careful use of his own small patrimony and by his wife’s money. Men knew that he was rich, but no one knew the extent of his wealth.” [Trollope: The Prime Minister]

Literary Modernism rejected this approach.

In chapter seven of his novel Ulysses – first published as a whole in 1922 – James Joyce describes one of the main characters, Leopold Bloom, walking into a Dublin newspaper office:

“He pushed in the glass swingdoor and entered, stepping over strewn packing paper. Through a lane of clanking drums he made his way.

WITH UNFEIGNED REGRET IT IS WE ANNOUNCE THE DISSOLUTION OF A MOST RESPECTED DUBLIN BURGESS

Thumping. Thump. This morning the remains of the late Mr Patrick Dignam. Machines. Smash a man to atoms if they got him caught. Rule the world today.

HOW A GREAT DAILY ORGAN IS TURNED OUT

It’s the ads and side features sell a weekly, not the stale news in the official gazette. Queen Anne is dead. Published by authority in the year one thousand and. Demesne situate in the townland of Rosenallis, barony of Tinnahinch. To all whom it may concern schedule pursuant to statute showing return of number of mules and jennets exported from Ballina. Nature notes. Cartoons. Phil Blake’s weekly Pat and Bull story. Uncle Toby’s page for tiny tots.”

Understandably, sceptical readers at first simply thought that Joyce was hopeless at telling a story. It’s hard to follow what’s going on: it seems to be a jumble of stray thoughts. In fact, he had a serious purpose: he was trying to reproduce what he saw as the chaos of modern experience. What’s going on inside our heads has become – he says – more like this: agitated, distracted, confusing.

We tend to consider Modernism as an artistic, cultural movement. We need to rediscover it as something useful to us on the flight home, something that reflects the most troubling aspects of our inner lives in the contemporary world. Artists like Joyce and Braque are tracking a development that’s still going on in our own lives: the loss of serenity.

There are three deep causes of this loss of serenity: busy-ness, competition and envy.

Modernism One: Busy-ness

Today, we’re expected to be always on the job. The idea of having precisely defined working hours no longer feels normal or natural. Essentially, you are not at work when work can reach you. If you can’t get out of range, you can’t ever really be away from work. Busy-ness depends upon how easy it is to get a claim on your attention and make a demand. Busyness has been increasing for centuries because of developments in the technology of access.

In early 18th-century Scotland, you might turn up in mid-summer at someone’s house – hoping to get them to do some work for you – only to be informed that they had ‘gone to London’ and that they would be ‘back by Christmas’. But if there was anything urgent that needed doing, you could always travel ten days and nights in a coach in pursuit of them. Or you could send a letter: it would take 110 hours and cost two-shillings – two days average wages.

But soon things got faster and cheaper. Technology got more sophisticated. By 1840, a letter would only take 33 hours and cost a penny (about GBP 5 today). However, if your quarry had gone overseas, they would be out of reach for weeks or months. At least, until 1866 when the first successful telegraph cable was laid across the Atlantic; though if they went to Australia they were safe until October 1872.

From the 1930s onwards, the telex meant that work could follow you. Extensive documents and files could follow you round the globe, so you would never have the excuse of not having the relevant material to hand. But the telex system was expensive and required special operators so there were restrictions on its use.

By 1993, email solved those problems – reducing the cost of communication to almost zero. Though you could very reasonably say that you didn’t get the email because you were on a train, at the airport or because you had stepped out of the office to have lunch.

Until 2007, that is, when the smartphone became mainstream. There are now few moments when one is legitimately beyond reach: in the shower perhaps – though there are very good waterproof cases. Or you could spend time in Big Bend National Park in Texas, where there is, as yet, almost no satellite coverage.

The history of communications can be told as a success story, of course. But it is also the record of the gradual conquest of privacy. We used to be protected by the impediments. People simply couldn’t make demands on us – not matter how much they might have wanted to. We’re not used to thinking of what the upside of impediments used to be.

Modernism Two: Competition

Obviously, competition is a key feature of the modern economy. Competition has been fostered by governments around the world because of the benefits it typically brings to customers and consumers: lower prices and a wider range of products.

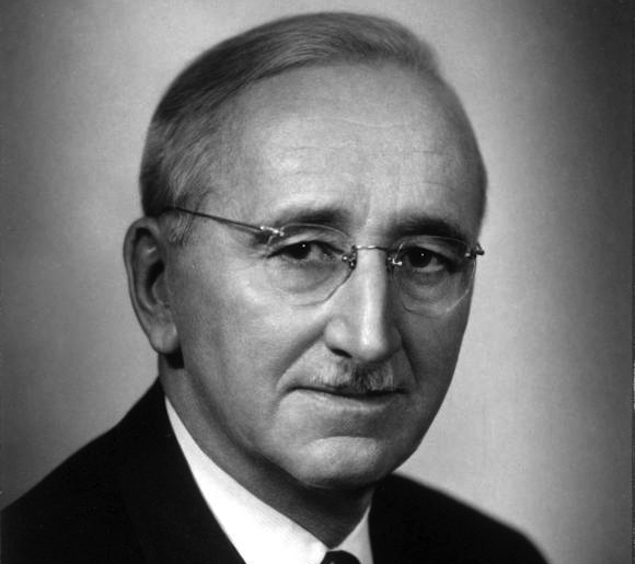

In the 20th century, the most influential advocate of Competition was the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek.

The intellectual architect of glitzy malls

Competition is designed to benefit the customer, rather than the company. And the reward is that when we go to buy things, we are offered lower prices and a wider range of options.

The cost comes in our working lives. Greater competition makes companies fight to win sales. Customers should be very fickle. They should have a lot of choice and be very willing to go with the better deal, wherever it comes from.

Companies have to strive to lower their prices or offer better, more enticing products. A firm that stands still will be overtaken by a more innovative or more efficient rival. Competition – ideally – keeps profits in check. If a firm has a bumper year and makes a big profit that should send a clear invitation to rival firms to move in, undercut, reduce the margins. A so-called efficient market really means one where it becomes ever more challenging to make a profit.

Internal competition in companies makes employees compete against one another. The successful may be well rewarded but there’s a permanent cull of the less efficient. And competition should also mean that many companies fail. A really efficient marketplace should be a really stressful place to work – because you’re always afraid of going out of business.

We have bought our happiness as consumers at the price of ourselves as producers. We had the option of running the economy for the sake of the worker or the consumer. The idea of ourselves as consumers dominated over the image of ourselves as workers. The huge collateral cost is that everyone at work is stressed. Efficiency brings anxiety, punishing hours and insecurity into the workplace.

Things that are familiar tend to feel natural. But actually it’s very odd that people in executive jobs are working so hard. History reminds us how much beyond the normal level we are operating.

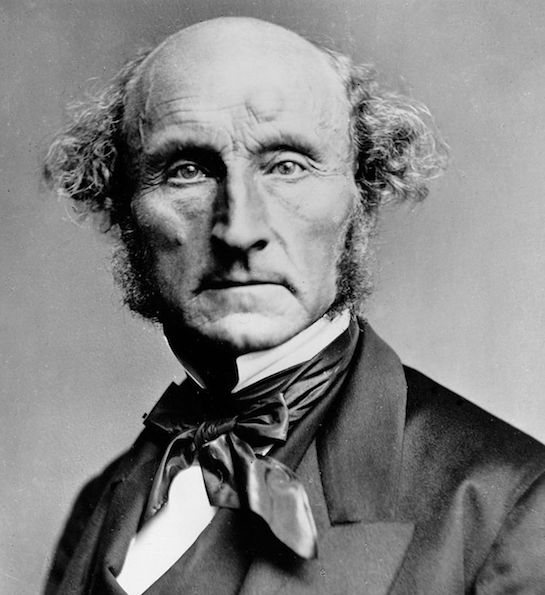

The philosopher John Stuart Mill worked in London for a vastly powerful business – the East India Company – from 1823 to 1858. He was mainly involved in policy formation and finished his career in one of the most senior roles: his job title was ‘The Examiner’. It was a highly responsible position; Mill was often required to give evidence on behalf of the Company before Parliamentary Committees. And he was very well paid. The job carried a salary of GBP 2000 – more than 20 times the average income. But while employed by the East India Company, Mill also managed to write some major and highly influential philosophical works – including, amongst many others, two monumental works: A System of Logic (1843) and The Principles of Political Economy (1848).

Mill was able to do all this because most afternoons, the East India Company’s offices were quiet. He could sit at his desk and get on with his own projects. Nobody was angry with him for doing so. If anything they were impressed by his work ethic.

John Stuart Mill

By an effort of will

Abandoned his natural bonhomie

And wrote on Political Economy

[The verse (improved by us) is by GK Chesterton]

In his report for the UK government’s 1864 School Enquiry Commission, the poet and civil servant Matthew Arnold advised the adoption in England of the workload for teachers in France: “A teacher at a French Lycée has his three four or five hours a day in lessons and conferences, then he is free.” He was specifically arguing against the practice in the England of school teachers working a few hours a week on top of this, supervising games.

Arnold and Mill – who were immensely respectable figures – show us that it was completely normal in the professional world of the mid-19th century to work around 20 hours a week. These were not people who were lazy or marginal in their careers. They used their free time in very constructive and ambitious ways. That’s why it was possible for the leading philosopher to be in business and for one of the major poets to work as a senior administrative officer.

Matthew Arnold – famous for taking it easy, writing poetry – and for reforming the education system

In some ways, we are simply unlucky to be living at this moment of intense commercial competition. In general, the idea of historical bad luck makes a lot of sense: people’s lives just happen to get played out against the background of huge events. 1938 was an unfortunate time to turn 21.

Good natured sympathetic innocence meeting with a really horrible historical movement

We understand that certain times were hard. The challenge today isn’t so concentrated and dramatic. But when you notice the difference between the life of Stuart Mill and us, it is extraordinary (that’s before we even mention housing and what a middle-class salary would have bought in London then and now). Mill and Arnold were able to hold down very good, high-level jobs for many years, but they faced nothing like the pressure and anxiety we have to live with.

It’s not just that a particular firm is very demanding or that one’s own shortcomings lead to weariness and insecurity: it’s the larger dynamic of market capitalism. Competition is why lunch for the lawyer on the plane usually means two minutes for a sandwich at the desk.

Modernism Three: Comparison, Envy and Disappointment

In the middle ages, if you lived in Bristol (which was then a busy but small sea port), you probably wouldn’t know much about what was happening in London, Paris or the royal courts of Spain. Less urgent information might simply never circulate around the country: that the ladies at court like to gather their hair up in net bags either side of their face; that they like red gauntlets sewn with pearls in floral patterns.

Blanche of Lancaster – wife of Henry IV – was the best dressed woman in late 14th-century England. But she couldn’t be fashionable – because it took too long for people to find out about what she was wearing.

The daughter of a well-to-do merchant in Bristol might take a great deal of interest in clothes, but she couldn’t compare herself with the grander ladies of London like Blanche – because she simply didn’t know what they were up to. And, in any case, Blanche hardly seemed to belong to the same species.

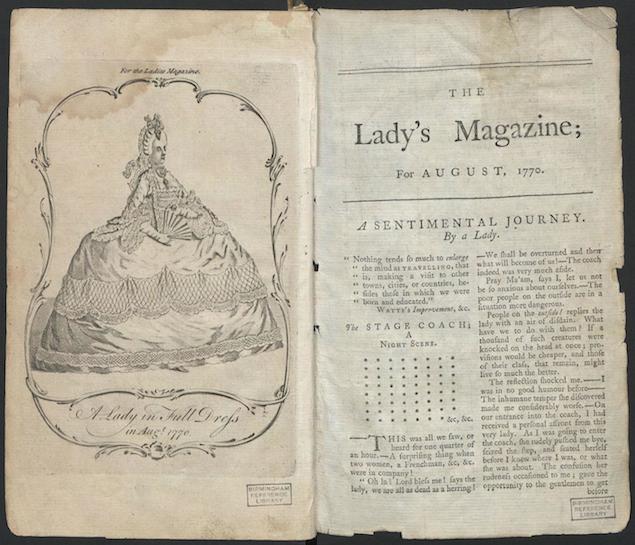

Then, in August 1770, the first edition of the Lady’s Magazine appeared.

Every month it carried detailed illustrations of what the most prestigious women were wearing. So news about bonnets and high waists could circulate rapidly.

Anyone reading it could at last compare their own clothes with those of the rich and well-connected in London. And so they were provided with the opportunity of experiencing a novel emotion: the feeling of being left out by history, by fashion, by everyone.

Up until then you could be left out, of course – but only by people who you knew, who lived around you. Your cousins didn’t take you berry-picking; the vicar didn’t ask you to dinner.

The magazine, however, presented itself as revealing what every lady in the land was was wearing – except you.

Actually ‘the Lady’ was not the disembodied voice of the spirit of the age speaking with universal authority. It was mainly concocted by a man called John Coote in a dusty little office, in an unprepossessing corner of London.

The new media of the 18th century was also teaching men the pains of missing out and being left behind: a yeoman farmer could learn from The Spectator that he was a clodhopper; The Tatler encouraged a local squire to recognise himself as a dull provincial.

The growth of modern technology created the opportunity for comparison. It needed better roads, more efficient printing, the use of special-coloured inks, an effective postal service to get a copy of the Lady’s Magazine into the hands of people in Newcastle and Exeter. And comparison opened the way to envy and disappointment.

The 18th century was introducing the world to the distinctive modern experience of comparison.

Officially, we are simply finding out about the world: we are informing ourselves about the lives of others – their style and achievements. We evolved as social creatures living in large groups: we’re primed by nature to be very interested in social hierarchies. It seem innocuous: an article about the most chic ski resort in Europe; a photo shoot of a young woman with amazingly beautiful legs; the new trend for rooftop lap-pools and a profile of how Uber’s Travis Kalanick made his billions. It’s just information about what’s happening around the world, but what it’s doing in our head is very harmful.

Envy is dependent on knowledge and hope. We only envy things that feel as if they are within our reach. Yet the world of the magazine is highly selective. In the magazine, ‘everyone’ is fashionable, everyone seems to have plenty of money, is aged between 18 and 25 and has a perfectly-shaped nose. Our natural instinct for comparison goes haywire as a result. By the standards of the magazine world, we are barely acceptable, we are on the lowest rung. We come away with a nagging sense of being plain, dowdy and short of cash. The life we lead – which used to seem fine – now looks so disappointing, because it compares so unfavourably with the picture of existence conjured up in the media. And so we are required to continually fight an internal battle staving off the envy and humiliation provoked by overexposure to the lives of the freakishly successful and beautiful few.

History dignifies our problems

Looking at three big factors in Modernism – the rise of busy-ness, the growth of competition and the vast increase in the circulation of envy-inducing information – shows that our problems around work are not the result of personal failings. This doesn’t make the problem go away. What it does is transform its meaning. History helps us reframe what we’re going through. It guides the re-interpretation of our own experience. You understand your problem in non-hysterical, non-panicky ways. There are three specific consolations of history:

It depersonalises

However intimate it all feels – the exhaustion, the relationship tension, the build up of demands, the ever increasing expectations – the fact is that one is not alone. Because these troubles arise out of big historical factors, they are necessarily going to be very widespread. You belong to a community of people who have this problem.

It shifts the direction of blame

History teaches us not to shout at the wrong person. It’s not your fault. And it’s not just some stupid managerial issue that’s getting you down. We can grasp why the problem won’t go away quickly or easily – why just changing jobs or getting divorced won’t necessarily solve the issue. History offers an insight into potentially mitigating factors around work.

Participation in the Grandeur of History

The real root of your problem is not the Frankfurt contracts, it’s this high-cultural issue known as Modernism. In general, we understand how much it can mean to people to see themselves in grand historical terms. Mourners at the funeral of Winston Churchill – which took place at the end of January 1965 – knew they were recognising more than the death of a single individual.

They were collectively witnessing the passing of an epoch. The Grandeur of History isn’t only about positive things which are shared. There is grandeur in recognising the scale of the collective traumas we go through together; they are so much bigger than us; they set the stage on which we lead our lives, we have no control over them.

We haven’t yet raised all the monuments we need:

The Arc de Triomphe gets us to see the grandeur of the huge, painful transformation of France during the Revolution. We could do with equally impressive reminders of the grandeur of the present. We need Arcs to: the heroes of Media Saturation and to Those Whose Leisure has been Sacrificed in the Age of Competition.

OUR WORK & OUR PARTNERS

Work threatens to blow up our relationships. There are four key complaints that signal the mounting levels of tension.

Complaint One: If you loved me, you wouldn’t work so hard

So often, work has a difficult impact on relationships. (Though the absence of work can be even worse). There’s a long list of complaints:

– you’re never around

– you’re always tired

– I never get you full attention; you’re obsessive; your work always comes first (I wanted to watch an episode of House of Cards with you at 10pm and you were still bashing away at a report)

– you come back stressed

The Ideology of Romanticism

Today, we tend to see our relationships in terms that were invented mainly in the late 18th century. The Romantic ideology of love emphasises:

– monogamy, sex as the expression of love

– candour, the sharing of all secrets

– the need to understand one another

– the importance of doing things together all the time

These ideas were revolutionary when they were introduced. And they were introduced by very particular kinds of people: who were young, leisured, well-off. Romanticism was invented on long summer evenings.

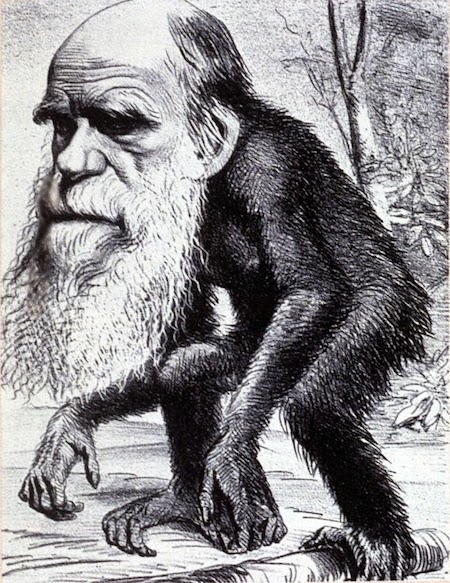

The main manual of Romanticism – the book that more than any other taught people how to think of love in this way – was The Sorrows of Young Werther. It was written by the German poet and philosopher Goethe, when he was in his mid-twenties. It tells the story of Werther’s love for Charlotte. He meets her at a dance and falls in love with her. Every emotional shift is described in compelling detail: the thrill of looking into her eyes, the agony that she does not love him back, the desperate longing to see her again after every parting, the moments of transcendent tenderness. For thirty years it was the most famous novel in the world (Napoleon read it seven times).

As his love for Charlotte grows, Werther is not distracted by the demands of a job. At one point, Werther describes how he usually passes the morning – before going over to Charlotte’s place for the afternoon and evening.

“In the morning at sunrise I go out to gather with my own hands the peas which are to serve for my dinner, I sit down to shell them, read some poetry during the intervals, and then, selecting a saucepan from the kitchen, fetch my own butter, put it on the fire, cover it up, and sit down to stir it as occasion requires.”

Werter reading to Charlotte. He was next expected at work in two-and-a-half years

For a while Werther does have a job: he takes up a rather undemanding post as a diplomat. But for months on end he’s free to do as he likes. It’s not a coincidence. Romantic love began as a full time undertaking. It was invented as a privileged, leisured experience. The ideal romantic couple would spend all their time together, they would spend hours talking about every detail of their emotional lives, they would always be going on long walks together in the evening. And the point of getting married would be to be able to do this more and more. Any reduction in the time spent together or lessening of the level of openness would be experienced in very alarming terms: it would begin to signal the death of love.

Romanticism meets Modern Capitalism

Romanticism and Capitalism are the two dominant system of ideas of our time: they guide the way we think and feel about the two things the usually matter most in our lives: relationships and work. But combining Romanticism and Modern Capitalism together is very, very difficult. It’s a hugely unfortunate historical clash. We live under two very powerful, but oddly incompatible systems. The impressive idea of Romantic love – with its ideals of closeness and openness – sits badly with the way work takes up so much of our time, fills our heads with complex demands and makes it very hard to switch off; and the insecurity around so much work makes it very hard to feel relaxed about taking things easy.

The aristocratic tradition of marriage

The modern view of work should ideally have been married up with the view of relationships that predominated in the French and English aristocracy up until the end of the 18th century.

A happy unromantic couple: John (far left) and Sarah (middle) with their children

The John 1st Duke and Sarah Duchess of Marlborough had a very strong marriage. They were the most successful economic and political couple in early 18th-century Europe, whose partnership took them from obscure poverty to vast wealth and power. But they spent long periods apart. Neither one was particularly surprised if they didn’t see the other for six months. And the idea of sexual fidelity did not apply.

Their expectations of a relationship were clear, limited and pragmatic. They would produce legitimate heirs. They would secure mutual prosperity and assist each other’s careers. They could have moments of great loyalty and closeness – but it wasn’t an everyday thing. They were not expected to share the same bedroom, or even live in the same house all the time. They weren’t continually complaining about not spending enough time together or about being too occupied with work. But nor were they doing something strange and unusual. The way they lived was conventional and acceptable.

We don’t realise to what an extent our feelings are guided by our sense of what is normal and of what we should expect from others. We are highly flexible creatures, but with a generally strong desire to fit in. There are many ways we could be living fine – if we had time to adjust and enough social support.

We need a revolution in marriage – from the current Romantic version to an updated version of the pragmatic, work-aligned aristocratic idea.

Complaint Two: I don’t know what’s on your mind

The Romantic vision of love is very keen on candour and sharing: according to the Romantic ideal, your lover is sensitive to and understands your moods and thoughts: you finish each other’s sentences; each knows what the other has on their mind. It can be a very attractive idea – but the level of communicative openness it assumes is at odds with the realities of a lot of modern work.

It’s hard to explain what’s going on at work

It’s hard to get your partner to really understand what your experience is like (and they may very likely be feeling the same way about you and their work). After a tricky day (or a tricky week) the tension has built up; the worries are circulating, work-related ideas fill one’s mind. All this preoccupation expresses itself in a range of not very endearing symptoms: grunting, sighing, brooding silence and a short-fused temper. The most innocuous sounding question ’how was your day?’ can elicit a growl or an explosion; a tiny irritation at home feels like this: one is already filled up with stress and irritation; a single drop more and a spill is inevitable.

One’s partner has to endure these symptoms without the real cause being properly explained. They can’t see all the stuff that is in the glass already. We find it extremely hard to lay out what has actually been going on at work in such a way that would lead the other person to understand what we’re going though – and therefore feel a degree of sympathy for our volatile state.

Unfortunately, we find it extremely difficult to undertake the expected explanation. It’s not really our fault. There are several big reasons why this is the case.

Description in general is hard

Work isn’t unusual in being hard to describe. The fact that something is very familiar to you doesn’t mean it is at all easy to put into words what it is like or what is going on. Bicycle gears are totally rational mechanisms for controlling the relationship between the speed the pedals are rotating at and the speed the wheels are turning. Describing in detail what is going on is fiendishly difficult (and very boring).

Impossible to put into words: like so much of work

Previously expectations of communication were much lower

The fact that explanation is tricky didn’t matter so much when expectations were low. When work was strongly divided on gender lines, there was often an assumption that work wouldn’t be much discussed at home, in a domestic setting. Family life was where the worker left work behind. The family didn’t feel shut out. It felt natural and therefore totally acceptable.

And in any case, jobs were often much simpler and their basic character was well understood by everyone. If you were a shepherd, a blacksmith, a miner or a housemaid, you were doing work that had been deeply familiar to everyone in the community for many generations. The advent of the factory system in the early 19th century brought new kinds of work – but often whole communities would be employed in roughly the same industries, so everyone would understand what it was like to glaze pottery (if you lived in Staffordshire) or operate a steam loom (if you lived around Manchester).

Today’s jobs are weirder and more strangely specialised. You might be

– advising on restructuring the billing system for an NHS trust;

– a senior order entry specialist scheduling shipments to customers;

– involved in the operational management of health and welfare benefit programs;

– a technical manager with extensive experience in IBM Data Collection suite, including Dimensions, with a track record in leading systems transformation projects.

Instructively, grown-up characters in children’s books rarely have such jobs. They are still more likely to be farmers, deliver the post or have a grocery stall at the local market – work that is essentially pre-modern. This tiny detail of modern publishing has a larger meaning: it’s a signal that we know that it’s very hard to explain modern jobs to a child, or indeed anyone else.

One’s work situation is changing fast…

Work is often like a fast moving, many stranded soap opera, with revolving characters and volatile themes. Keeping one’s partner on board would require constant updating:

‘The other Sarah – not the one I was telling you about yesterday who had the fight with the New York office over the legal reforms in Argentina, but the other one – who I mentioned two weeks ago when she was trying to get Ted – remember Ted? – to take Alison off the review committee. You’re with me? So, other Sarah was suggesting that I rejig the approach to the Générale Occidentale account. For once, she’s actually got a point. But it means I’m going to be working late on Tuesday. Now, let me fill you in on the apparently subtle, but actually fundamental, shift in our strategy toward the French financial services sector…”

Explaining properly – about why one day was more demanding than another, why a particular project is so stress-inducing or why the relationship with certain people involves special degrees of angst – would require immense levels of patience on both sides.

It would help if…

There was general acknowledging that the explanatory task is very difficult.

Theoretical physicists have it easy to the extent that everyone admits that their work is important and yet bafflingly difficult for outsiders to understand. If we don’t understand we don’t blame them. We humbly admit it’s all just too complicated. We need this tolerance to spread more widely. So that one could comfortably say things like: ‘my partner is in logistics; of course their work is too complex for me to understand properly.’

Art could take up some of the burden

In late 19th century England, the best understood work was that of a country vicar. This was due not to the simplicity of their work (it was actually quite complicated) but to the great efforts to explain it undertaken by the most accomplished novelists of the age. George Eliot and Anthony Trollope wrote numerous highly successful and highly accomplished works detailing the working lives of the Church of England clergy. They explained in great detail (but in ways that won them huge audiences) the secret pains and quiet triumphs of such work.

Anthony Trollope – the leading 19th-century writer of entertaining novels – was determined to make the world understand the day-to-day working lives of Anglican vicars

We haven’t yet seen this happen around more typical modern employment.

Complaint: I have to do all the shit work around here/I’m tired of picking up your socks

One of the ways work is at odds with domestic life is expressed via intemperate conversations about who cleans the loo. (Or takes out the rubbish, or renews the household insurance or cleans the fridge.) It’s partly because when people are busy with job work there’s less time and energy left over for work around the house.

The modern ideology of work assigns the domestic sphere a low status. Work around the house isn’t paid, and that means it can’t be important. And it’s associated, historically, with socially subordinate positions: the scullery maid, the footman. So, we tend not to take household management seriously. We don’t give it patient and serious thought. We’re not used to recognising and admiring the relevant skills. (We admire people who can drive fast, but not those who can make a bed perfectly at high-speed.) In Modernity, paid work has sucked up all the prestige.

And our Romantic ideas about love are also not very concerned with household management.

No one is worrying about who dusted the shelves

Our Romantic ideology privileges emotion over household management. It’s the intensity of the feeling the couple has for each other that counts – not the extent to which they can co-operate around cleaning the bathroom or managing the household accounts. If one were to ask is vacuuming more romantic than a weekend in Paris the answer – supposedly is too obvious to be worth giving. And yet a collaborative attitude to cleaning rugs is a better indicator of the health of a relationship than a shared interest in bars in the troisième. The irony is we play down the domestic as if it didn’t matter – yet actually this is where things so often get very fraught in relationships.

An unfortunate historical moment …

We live at a moment that is quite odd by historical standards: a period when pretty much everyone is involved (even if only a little) in housework.

Today, we tend to think of the idea of having a servant as an ultra-high end luxury.

But for large swathes of humanity, very large numbers of people in fact employed other people to help them domestically. In 1850 in the UK, for example, families with an income of GBP 300 a year (the basic income of any managerial job) would typically have two live-in servants. A clerk on half that (GBP 150 a year) would usually employ a full-time maid. Even just renting a room almost always meant having a shared servant.

The domestic service sector really came to an end because there were more productive things for people to do. In the most productive economies it has become prohibitively expensive to employ a fellow citizen to live in your house and make you cups of tea, dust the mantlepiece and clean the bath taps.

And in the future, it is unlikely that there will be much domestic work for people to do (unless they want to do it for fun). The technological developments of the 1950s and 1960s – the vacuum cleaners and dishwashers and tumble driers – made domestic work a bit less cumbersome, but they didn’t bring it to an end. The long-promised robotic servants who really would take domestic chores out of our hands haven’t arrived yet.

But, of course, they will become standard – eventually. They might be cheap and common by 2050. So there will have been a gap period from about 1950 to 2050 where domestic work was neither the province of servants nor of robots. A century is nothing in the big sweep of history. It’s just odd and very challenging that we happen to be living in it at the moment.

Complaint: You’re too busy for me

Both partners are tired and depleted. She wants him to see her friends. He wants her to do some complicated sexual thing. They’re too tired to please each other. And they each have what feels like a justified point of complaint against the other: you’re too busy for me.

People feel guilty; they feel they should go to bed earlier. Perhaps if they took magnesium supplements, they’d feel more perky. But the real cause is probably just work: too much, too demanding, too relentless.

We’ve been very reluctant to admit that the demands of certain areas of high-pressure modern work might really not be very compatible with having a relationship. In order to get on efficiently with other tasks, you probably shouldn’t be trying to have a relationship and possibly raise a family as well.

Which raises a question that sounds deeply strange to us:

Might you really need to be celibate to do certain jobs?

For much of history, the question was taken very seriously – and quite often the answer was a definite ‘yes’. A whole range of jobs were seen as incompatible with relationships. They weren’t necessarily saying you need to be chaste and avoid sex; it was the demands on time and the emotions that was the real focus of concern.

St Hilda of Whitby was one of the most powerful and accomplished women in the early history of England.

She was a very senior administrator, running large agricultural enterprises; she was a management consultant to kings and princes. She was a leading educationalist. And she did all this while being noted for her good temper. Of course, she was unmarried. It’s not that because she was a nun she wasn’t allowed to get married and so had to make the best of her work opportunities without a supportive home life. The line of thought ran the other way round. She was able to have a stellar career and achieve so much for the community because she was free of the demands of relationships and domestic life. Being a nun meant she lived in an efficient collective household – she would be supplied with meals, laundry and heating without having to organise everything for herself.

It was an approach to certain kinds of work – intellectual, administrative and cultural – that persisted for many centuries. In 1900, academia in the UK was still almost entirely a career for the unmarried.

Fellows of King’s College, Cambridge in 1900: not being married was one of the job requirements

The view was that certain kinds of jobs require such effort and continuous devotion and they loom so large in your imagination that you really shouldn’t try to combine them with the duties of a relationship, a family and looking after your own home. To do them properly, you should live in very well-organised commune (like a monastery or a college), you should be single and you should socialise mainly with people who are involved in the same kind of work, because they will understand you and also be able to help you.

This reminds us that we’re asking ourselves to do lots of complicated things at once. No wonder we squabble, feel resentment and the occasional burst of despair. We think it should be easy, if you’re a half-decent person, to be a success at work and an excellent domestic partner. But your job requires so much effort. Your sneaking background suspicion that someone who does your job might be too busy to empty the bins or make the bed could actually just be true. You deserve a lot of sympathy.

CHILDREN

Accompanied by a discrete but substantial security detail, the British Prime Minister, David Cameron, likes to take his daughter Florence to nursery school a few blocks from Number 10.

Ideally, he’d do it every day. But the demands on his diary make it a rare event.

Sadly, a special occasion

Historically, it is very odd for Prime Ministers – or indeed anyone with an executive role – to spend much of their day attending to the needs of their own children. People weren’t heartless, they just didn’t think that it was particularly good for children to spend a lot of time with their parents. Many people feared ‘spoiling’ their children by overt displays of affection. In fact, it wasn’t until the early 1950s that this view started to change dramatically.

A number of researchers in the area of child development – especially an English doctor and psychoanalyst, John Bowlby – stressed the importance of continuous and close relationships with parents. He demonstrated the value of a warm, reassuring parental figure for the good development of the child.

“All the cuddling and playing, the intimacies of suckling by which a child learns the comfort of his mother’s body, the rituals of washing and dressing by which through her pride and tenderness towards his little limbs he learns the values of his own…” Such experiences teach a basic trust: that difficulties can be managed; that slip-ups are only that and can be put right, that we are naturally entitled to be treated with kindness and consideration, without having to do anything to earn this and without having to make special pleas or demands. “It is as if maternal care were as necessary for the proper development of personality as vitamin D for the proper development of bones.”

He didn’t mean for it to happen, but Bowlby’s insights into the principles of child development opened a new landscape of pain for modern parents. One is upset and worried about not making it back in time to read for bed. A tender part of us has been awakened and now aches.

The parent returning from a business trip frets at the nights they have missed bath time, the number of bed-time stories they didn’t read.

They are worries which would not have occurred to a knight returning from the Crusades.

In 1095 – when his son Baldwin was two – Count Robert of Flanders, headed overseas on the First Crusade to the Holy Land. He came back home in August 1099. By which time he had missed 1,460 successive bedtime stories.

Robert: unfazed by the number of unread stories

But it didn’t make Robert feel guilty or sad. Because in 11th-century Europe, being a very good father was not assessed in terms of quantity of contact.

In the light of our improved understanding of the needs of the child, our vision of the decent parent has become much more demanding: a good parent devotes a lot of time and thought to their child, they are present at crucial moments. To be a good parent has become much more emotionally demanding than ever before.

Our best – and very time consuming – ideas about how to raise a child have arrived on the scene at a very awkward moment. Because we’ve also discovered some crucial things about productivity and efficiency. Competitive, open markets have been astonishingly productive but they leave us challenged around time. Our best ideas about how to run an economy and our best ideas about how to raise families are completely at odds.

Against work-life balance

Finding a comfortable, harmonious balance between the demands of work and the needs of children is a very tantalising thought. It sounds like obviously such a good idea. And we can always find a few people in the world who seem to achieve it with ease – just as there are people who are good at high-wire cycling.

There are also people who achieve work-life balance

We should understand that attempting to have – at the same time – a good home life and a good work life is an inescapably very difficult thing.

It’s possible to pull it off: it does very rarely happen. But it’s very unlikely that you will be one of these people. We end up getting frustrated and angry with ourselves (and our partners) for failing to attain this very elusive condition. One might – with similar levels of justice – berate oneself for not combining a job in the accounts department of a supermarket chain with giving piano recitals at Grosser Musikvereinssaal in Vienna; or complaining that one’s partner is always failing to win vast sums in the Spanish lottery. It’s very unhelpful to imagine that we can have it all. Because even what are actually very worthy efforts look puny and disappointing by comparison.

The consoling thing is that the failure isn’t personal. It isn’t one’s own incompetence or lack of drive that sets work and home life at odds. We just happen to be living at a point in history where two big, opposed themes are very powerful. We have demanding ideas about the needs of families and relationships and we have demanding ideas about work, efficiency, profit and competition. Both are founded in crucial insights. It’s not our fault that they are opposed. But it does mean that we deserve a high dose of sympathy for the very tricky situation we happen to find ourselves in.

CONCLUSION

For untold generations work was simply a matter of maintaining the status quo.

Très riches heures (June)

Those who laboured in the fields might have had marginally better or worse years. But no matter how diligently they raked or with how much skill they wielded the scythe, they could never essentially change their lot. That was decided by birth – and could not usually be changed by their own efforts, however great.

For the whole of the 19th century, the greatest place of hope in the world was New York, because it held open a fundamental idea – which overturned the static condition of the farm workers: irrespective of where you had started you could – through work and a good character – attain a full measure of success and prosperity there. Unlike almost anywhere else in the world, where your prospects were largely determined by the chances of birth.

In particular, it was capitalism which seemed to be the bringer of opportunity. Everyone was familiar with its less alluring sides: unemployment, huge factories. But what capitalism promoted was the idea of personal progress through a job. Competition and free markets would give opportunity to hard work and talent. You could rise. And prices would fall – competition for sales would lead to higher standards of living and lower costs.

The beautiful idea of capitalism … Careers and happiness open to all

Now everywhere is New York. In a couple of respects, capitalism has delivered on this promise. The prices of many goods have fallen. The kinds of lives we can lead, in material terms, has been transformed.

Across the UK in 1930, the average family spent 55% of its income on food. In fact, around 5% of all income went just on that. Today, for a typical British family, around 10% of the weekly budget goes on food. And only about 0.5% of a family’s income goes on bread.

However, there are other ways in which the capitalist dream has not turned out as expected. It doesn’t deliver the level of satisfaction and contentment that was anticipated around work.

Five factors of modern work experience undermine the promise of capitalism.

One: The necessary failure of ambition

Capitalism distributes ambitions very broadly and in a way very generously – but also very cruelly.

Graduates of the of Wharton School 2004 Executive MBA

By many measures, the graduates of a decade or so ago have almost all done very well. They earn well above the national average income. They hold responsible positions. They fly business class. But these external measures are not ones which have most psychological force. We measure ourselves against those we feel are in our peer group and in the light of our highest hopes.

By these standards, capitalism has a stern message to send to the graduates of the world’s leading business schools.

To have any chance of getting to the very top, you have to be absolutely determined to get there. You have to invest you time, your efforts, your soul in getting there. You have to really want it. But, that won’t be enough. Most of you will fail in this ambition. And you will be haunted by that failure. You will look at the photo and envy the few who made it.

It is a statistical law. The number of CEO positions is very limited. The number of graduates for elite business schools is quite large. Many people are competing very eagerly for the small number of prize jobs. Most must fail. They fail by a very high standard. But, since it is the standard set by their own ambition, it is the one they use to measure themselves.

There’s constant envy. There are a couple of people who make it through the regular cullings at McKinsey; there’s someone who is linked to one of the great startups and has made a significant fortune; there’s the person who’s had a great run as a staffer at the White House. In comparison your own career feels lacklustre.

At social gatherings you wince at the sight of the words on your own business card: Associate Vice-President: a title designed to sound big to outsiders. But insiders – like all your friends – know it means your career has stalled. You worry that your partner doesn’t fully respect you. When you got together, a few years ago, you both used to talk a lot about the future. Now it’s as if your partner is avoiding the topic of work. The dreams invested in you – by your family, your earlier self – haven’t come true. You feel ashamed.

It’s tempting to laugh at people without much money who hope to win the lottery. The desire to win makes sense – obviously. It’s just that the statistics are grim. They’re shooting at a tiny, very distant target. Failure is almost inevitable. But there’s an executive class version of this. And yet ambition – the hope of doing well in work – isn’t an optional add on. It’s actually central to how capitalism works: companies require all this competition for the top places; it needs a lot of people to aim much higher than they can achieve. For a few to succeed and be effective, many must try and fail. Collective efficiency is won at the price of many frustrated lives.

Two: We have to abandon many version of who we could be

In 1845 – when modern capitalism was moving into a higher gear, its most famous critic put a finger on one of its drawbacks, and dreamed of an ideal solution:

“In communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.” [Marx, German Ideology, 1845]

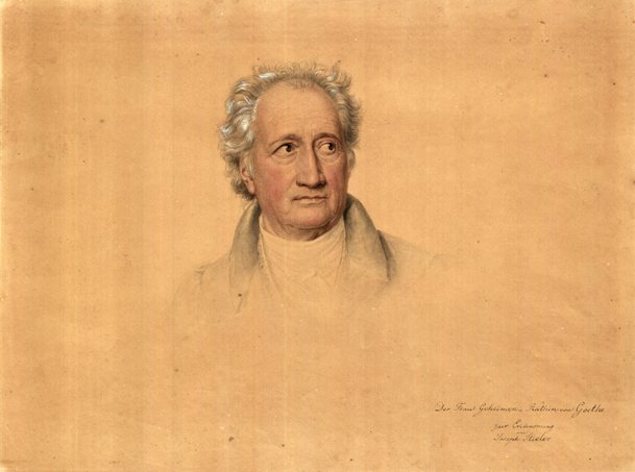

Marx was tapping into a widespread longing. Each person has so much potential. The key exemplar – in Marx’s own lifetime – of the full human life was Goethe:

He was an individual who seemed to have fully explored the range of his ambition and longing – who had been married and had a family, but who also had a wildly adventurous romantic and sexual life; who had travelled and made a wonderful home; who had been a poet and thinker, but also a diplomat government minister, and political advisor, who had made discoveries in science.

Goethe is the grown-up, high-cultural version of a widespread instinct. Before they have much understanding of the reality of work, a child will typically lay out a long list of ‘what I’d like to be when I grow up’: an astronaut, inventor, bus driver, champion trampoliner, model, doctor, explorer… Every one of these jobs has spoken to some part of the child’s identity. But the kind of life Goethe led (and that a child might want) has become ever more unusual. The ideal rounded, Renaissance individual has come ever more into conflict with the ideology of modern work.

Our hopes of a full life establish a standard by which we are almost certain to fail. It’s a harsh truth: we are all likely to die with significant, lovely parts of ourselves unexplored. Some of the best parts of our potential will remain undeveloped. Our best plans and projects will largely go unrealised.

Capitalism requires specialisation and devotion. So in order to survive and get on in a competitive, market-oriented economy, we‘re going to have to be very selective about the things we focus on, and we’re going to have to give huge quantities of time (huge parts of our lives) to these things. As a society, we benefit if someone has put 25,000 hours into dental hygiene or 36,000 hours into data entry systems – but the personal cost is the loss of all the other things we might have done or been.

We can dream of so much more than we will ever be able to live out. Every day we will be reminded of what has had to be sacrificed.

Three: It is impossible to be calm

For much of western history, it would have been unthinkable to have had a major industry concerned with calming people down. Early nights, nothing going on, simple routines repeated day after day were not needed as special solutions to anxiety because they were, for so many people, the normal condition of everyday life.

Where everyone (almost) lived until the day before yesterday, historically speaking. Reducing stimulation was not necessary.

It’s only when – as now – that anxiety and agitation are omnipresent in our lives that we built up a big collective interest in the search for tranquility.

This search started to take off at much the same time as the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, when towns were growing rapidly and factories springing up. Increasingly, people started to delight in the idea that far away, in some new and unspoilt portion of the world, they could find true ease and relaxation. They could get away from the mounting pressure of home.

The 18th-century artist William Hodges was especially taken by the calming aspects of the island of Tahiti (first visited by westerners only in 1768).

Such images speak to our longing for calm and ease – for a simple natural, unanxious life. You too could have this life – they say – but you’d have to go to Tahiti, which will take five months and you’ll probably be attacked by pirates on the way; and it may not be quite as Hodges portrays it when you get there.

Today a huge industry exists to get us to these places.

A large part of the modern meaning of luxury is that you will be able to calm down; you will be less pressured; you will be able to switch off and get away from it all.

It is an attitude to travel entirely at odds with that which prevailed in earlier ages, when the purpose of travel was to seek stimulation, adventure. It never quite works. The luxury cabanas of the Maldives are the recipients of extraordinary amounts of frustration and angst.

It’s not our fault that we are agitated. Calm and tranquility depend on the thought that one has enough for tomorrow, that the challenges of the next period are ones we already know how to meet: we feel calm because we feel secure. But the conditions of modern life make such a feeling of calm very elusive. So even if we do get the prosperity and advancement that capitalism promised, we still end up anxious.

Four: The permanent existential crisis of business

Work intersects with a basic feature of the human condition: we make the wrong choices. The natural ideal of a choice – of course – is that you are fully informed about the significance of the various options. You can then select the one that best fits your needs. But the reality isn’t usually like this, of course.

Existentialist philosophers – most notably Jean Paul Sartre – were keenly attentive to the fact that usually, when we chose, we don’t know anything like enough about the various options.

Sartre: We’re forced to choose, even though we don’t actually know what’s the right thing to do

We lack the relevant information and experience. And yet we have to make decisions that will have huge implications for our own lives – and the lives of others. Should we expand into the South Korean market? Is this the time for a large scale rebranding exercise? Do I resign if I don’t get this promotion? Should I take the job in New York – or take up the offer in Tangiers? If my partner’s career takes them to Germany, do I follow, or do we break up over this? If there are children, do I take on more work (to pay for things) or less work (to spend more time around them)? Should you try to get into the property market now, or wait for a correction?

Life demands choices constantly, and we will by definition screw a great many up so that by the time you’ve reached 35, you will have made 150 big decisions, and 15 might be very, very wrong and you will be paying for this for the rest of your life.

Put someone long enough on earth and they will, through no particular evil quality, tie themselves up in extraordinary knots. They will be assailed by regrets. They will be eaten up every day by the thought that if only they had acted differently 10 years ago, things would be much better today.

Orestes pursued by ‘the Furies’ of remorse and regret: an extreme image of a normal experience

It’s a theme that Greek tragic writers were sympathetic to. They thought that the key to dealing with it was to acknowledge the inevitability of regret. They didn’t think that if only we were smart and honest and well-intentioned we could get through life with few regrets and without the pangs of remorse.

They were particularly taken with the life story of Oedipus. On a journey, the talented and ambitious Oedipus was stopped by people he thought were robbers. He struck out at their leader and killed him. What no one knew at the time time was that the man he killed was actually his father. Of course, if this had been clear, everything would have been different. What the Greeks so liked about the story was the sense that it wasn’t the fault of Oedipus. But much later when he finds out what he’s done he is, of course, tormented by guilt and sorrow.

It’s a message we benefit from hearing quite often. Because what helps with regret is the knowledge that – in fact – every life is burdened by regret in some shape or form. The ‘regret-free life’ exists only in French cabaret songs.

I spent 25 years trying to please my father (and he didn’t care)

James Packer inherited Consolidated Press Holdings Limited, which controls large investment investments mainly in casinos.

James Gorman (CEO morgan Stanley): I regret never having had any real friends at work

The way to diminish regret is to alleviate the sense that one had the option to choose correctly – and failed.

Five: We’re wrongly designed for modern work…

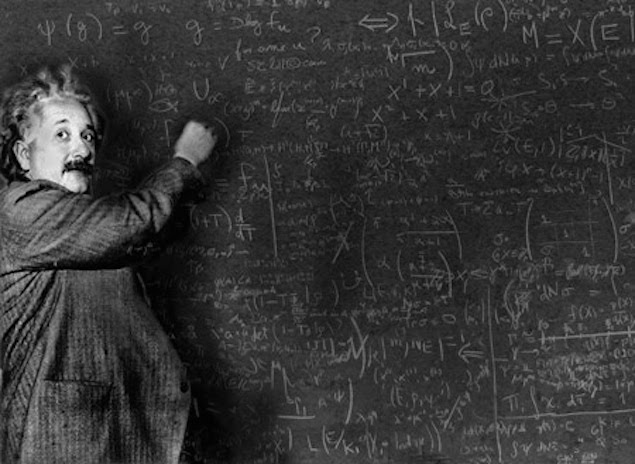

Evolution is one of the biggest modern ideas. It looks into the past and explains how we got here and why we are as we are. The main person who discovered how evolution works – Charles Darwin – was deeply unpopular with large swathes of the population in 19th-century England.

Darwin was mocked because he caused deep offence

By saying that ‘we’re descended from Apes’, Darwin’s reminding us that we carry with us a lot of baggage. We evolved (in the distant past) because certain characteristics worked well in environments very different from the ones we live in today.

Evolution (via gene mutation and reproduction) works to a very, very slow clock; big changes take hundreds of generations, so it lags weirdly when there are rapid changes to the human context.

We’ve evolved to have a strong liking for sweet things (which worked really well when the sweetest things around was a papaya or a banana – because IN THAT ENVIRONMENT, a craving for sweet things is a good guide to what will help you flourish. But IN OUR ENVIRONMENT a craving for sweet things takes you to things that are unhealthy. But because this is an evolved desire, it’s very, very hard to turn it off.

We’ve evolved to be suited to this kind of life. Evolution means we’re going to be saddled with some very inconvenient but maddeningly deep-rooted tendencies

For instance, we’ve evolved so that at times of conflict we get aggressive. It’s brilliant if what you are afraid of is a bear-size hyena or a saber-toothed cat. But if what you are afraid of is psychologically complex: getting trapped on a project with a colleague who doesn’t understand you or worries about being taken for granted, then ideally you want to approach this anxiety with as much cool reason and patience as possible; evolution, however, is still dealing with the terrors of the savanna and so pumps up our panic levels to the maximum.

We’ve evolved to have relatively short attentions spans and to be very easily distracted by brightly-coloured moving things. Which worked beautifully when we needed to be on the look out for snakes in the long grass – and which goes some way to explaining why Times Square is one of the biggest tourist attractions on the planet.

But this jumpy, highly visual kind of mind is ill-adapted to much of the work we need to do day-to-day at work.

The lag in genetic evolution means that our brains are brilliantly adapted to the situation we used to be in; but are tragicomically mismatched to our modern environment.

Evolution tells us why we struggle to fit the huge demands of work into our lives. We are trying to get ourselves to do something that’s very hard for us.

It changes the scale of our troubles. Although so often it seems incredibly personal that one fails to combine work harmoniously with family life or with exercise or with maintaining old friendships, the charge should not really be laid primarily against oneself. The fault lies with something much larger than our own individual failings (real though those are). It lies with where we are in history, with the nature of the economy and in the slow pace of evolution.