Work • Consumption & Need

Is the Modern World Too ‘Materialistic’?

It’s often said that the problem with modern societies is that they are far too ‘materialistic’ – which is taken to mean that we are far too interested in buying objects. This is not entirely fair. We are indeed materialistic, but not primarily because we buy a lot; rather because we harbour an immense faith in the power of whatever we do buy to have a decisive impact on our state of mind. We aren’t so much greedy as extremely hopeful.

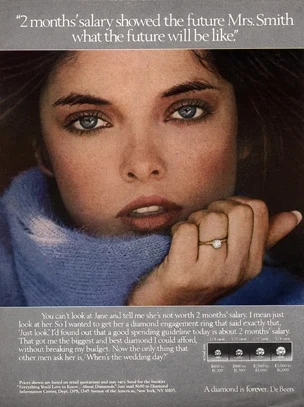

We may, for example, develop a faith that a certain kind of diamond ring will render us able to sustain a long-lasting and harmonious relationship.

Or that particular items of clothing will ensure the interest and acclaim of the world.

Or that a soft drink will be able to assist us in healing the divisions in our family.

Our belief that complicated psychological ambitions might be accomplished through the possession of an object is the distinctive and poignant feature of our age. In our reverence for the transformative capacity of material things, we are a little like the Bakongo or Songye peoples of the Congo Basin, who rely on what anthropologists know as fetish objects, small wooden figures (often traded for very high sums) which are thought to be able to oversee major interventions in daily life: to sort out troubled relationships, help adolescents on the journey to adulthood, lift the moods of the downcast or dissolve family tensions. Like the Bakongos or Songyes, we too hope that our fetish objects will have success in transforming complex and elusive bits of our internal functioning: a soap might bring an end to anxiety, a bag could assist one in recovering hope, a watch could unblock a relationship with a wary child.

Almost all religions have in some way made use of material objects. They’ve invested in particular sorts of furniture, clothes, buildings, statues and images – and seen these as adjuncts to their spiritual mission. But this has not been without controversy within the religions themselves. Reliance on material forms has intermittently come under fire from a minority of believers who have argued that spiritual transformations should only ever require spiritual means; material objects being wholly redundant to the project of healing the soul.

Such religious hostility to materialism reached its European high point in the early Reformation when outbreaks of systematic looting and destruction known as iconoclasm broke out across parts of England, the Low Countries and Germany. The spiritual opponents of materialism burnt elegant priestly robes, smashed paintings, chopped pulpits into firewood and snapped the heads off statues – in order forcefully to make the point that anyone with a spiritual goal in mind should avoid harbouring the slightest interest in material forms.

However, the mainstreams of most religions have never been so definitive. Interestingly for the modern age (which wrestles with its own iconoclasts around consumerism), they have allowed a place for materialism. They have, with useful caveats, hinted that there might be such a thing as ‘good materialism.’

Good materialism is the fruit of a search for a genuine and balanced place for material objects within the overall context of a good life. It means neither assuming, like certain iconoclasts will, that all material things must be superfluous and an interest in them therefore derisory and suspect. But nor does it mean imagining that material things must have a quasi-magical power to ease complicated psychological dilemmas. Good materialism suggests that material things can contribute to, but must never replace, the arduous psychological work inevitably required to achieve fulfilment, connection, purpose and peace of mind.

Insofar as material objects can be helpful, it is when they embody in visible form attitudes and dispositions with spiritual analogies that are prone to be forgotten in the noise of daily life – and so benefit from being made more prominent in matter. For example, a Zen Buddhist bowl might pull its viewer back to certain key tenets of Zen’s belief-system through its shape and design: its modesty, its gracious acceptance of imperfection, its dignified simplicity. Certain spiritual ideas might be easier for a believer to remember and put into practice when a material equivalent was continually available to be absorbed by their eyes.

Similarly, for a Christian, the decoration of an Alpine wooden chapel – with its slightly crooked pews and walls and a naive rendition of the Virgin above the altar – might make particular ideas of humility or patient effort feel more recognisable and real than they would have done if they had simply been explained in a book. The peace one was looking for within would have robust encouragement from outward forms. In such cases, material objects will assume the status of goads or encouragers. Their design points to an inner destination – even if it is one to which they can’t take us all on their own.

This philosophy of material objects can be applied as much to the consumer realm. A secular object may – just like a religious one – embody an important set of values; it might be hope or courage, straightforwardness or sweetness. By having the object around us, the values it refers to, and that might otherwise have been intermittent in our thoughts, have a chance to grow more stable, resilient and convincing and to prompt pieces of inner evolution. A certain kind of chair might encourage an attitude of acceptance; a pair of sunglasses might help a shy person to keep rediscovering reserves of confidence; there might be a role for a brightly coloured new top in cementing a break with a sorrowful past.

It isn’t therefore that material objects have no role whatsoever in fulfilment. It’s that the main effort we will need to make will, unfortunately, always have to involve an engagement with our psyches and those of others. Calm isn’t going come simply from flying to a particular destination and having an outdoor bath; it will be the result of studying the feint sources of our long-buried anxieties over many patient months. Likewise, friendship won’t magically emerge from a certain sort of soft drink, it will require that we make ourselves available to someone, that we dare to be vulnerable around them and know how to interpret what they tell us with imagination. And a good family can’t spring ready-made from the acquisition of a new timepiece, it will involve being patient around the many trials of adolescence and the courage to lay down boundaries which might involve short-term tensions and recriminations.

Modernity has made us feel less prepared for a lot of this. It has encouraged us to have excessive faith in quasi-magical solutions originating out of material things. It has encouraged us to believe that objects can have a greater effect than they ever can – which has in turn, in certain quarters, bred a furious iconoclasm which, to no good end, has rendered us guilty for our supposed greed. It can matter immensely to our state of mind that the colours and forms in our vicinity are a certain way, that there is a particular atmosphere and spirit to the things that we see and touch every day. However, beauty can only ever be the handmaiden of wisdom, it cannot be its sole catalyst. We should be careful neither to decry nor excessively to celebrate material life: we should ensure that the objects we invest in, and tire ourselves and the planet by manufacturing, are those that stand the best chance of encouraging our higher, better natures.

How to Survive the Modern World

New Book Out Now

How to Survive the Modern World is the ultimate guide to navigating our unusual times. It identifies a range of themes — our relationship to the news media, our assumptions about money and our careers, our admiration for science and technology and our belief in individualism and secularism – that present acute challenges to our mental wellbeing.

The emphasis isn’t just on understanding modern times but also on knowing how we can best relate to the difficulties these present, pointing us towards a saner individual and collective future.