Self-Knowledge • Know Yourself

Know Yourself — Socrates and How to Develop Self-Knowledge

In Ancient Greece, the philosopher Socrates famously declared that the unexamined life was not worth living. Asked to sum up what all philosophical commandments could be reduced to, he replied: ‘Know yourself.’

Knowing yourself has extraordinary prestige in our culture. It has been framed as quite literally the meaning of life.

This sounds, when one hears it, highly plausible, yet so plausible it’s worth pausing to ask a few more questions. Just why is self-knowledge such a prestigious good? What are the dangers that come with a lack of self-knowledge? And what do we in fact need to know about ourselves? How do we come to learn such things? And why is self-knowledge difficult to attain?

When we speak about self-knowledge, we’re alluding to a particular kind of knowledge – generally of an emotional or psychological kind. There are a million things you could potentially know about yourself. Here are some options:

-

- On what day of the week were you born?

- Were you able to pick up a raisin between your fore-finger and thumb when you were five months old?

- Are you more an introvert or an extrovert?

- How does your relationship with your father influence your career ambitions?

- What kind of picnic person are you: morning or evening? River-bank, park or hill?

Most of us would recognise that questions 3 and 4 are ones worth knowing; the others, not so much.

In other words, not everything that we can know about ourselves is all that important to find out. Here we want to focus on the areas of self-knowledge that matter most in life: the areas concerned with the inner psychological core of the self.

The key bits of self-knowledge we’ll be interested in are:

- — What kind of person are you characteristically attracted to in love

- — What difficult patterns of behaviour are you prey to in relationships

- — What are your talents at work

- — What problems do you have around success/failure

- — How are you about feedback

- — What do you do when you have been frustrated by life

- — What kind of taste do you have

- — Can you distinguish between your passing bodily-based emotions and your more rational thoughts

If you have solid answers to these issues, you’ll be able to speak of yourself as someone with an adequate degree of self-knowledge.

1. Why and Where Does Self-Knowledge Matter?

Self-knowledge is important for one central reason: because it offers us a route to greater happiness and fulfilment.

A lack of self-knowledge leaves you open to accident and mistaken ambitions.

Armed with the right sort of self-knowledge, we have a greater chance of avoiding errors in our dealings with others and in the formulation of our life choices.

Let’s look at some examples of areas where self-knowledge matters

LOVE

Without self-knowledge, all sorts of problems may occur:

1. We choose the wrong partners, trying to get together with people who don’t really suit us, because we don’t understand our own needs

When first looking out for a partner, the requirements we come up with are coloured often by a beautiful non-specific sentimental vagueness: we’ll say we really want to find someone who is ‘kind’ or ‘fun to be with’, ‘attractive’ or ‘up for adventure…’

It isn’t that such desires are wrong, they are just not remotely precise enough in their understanding of what we in particular are going to require in order to stand a chance of being happy – or, more accurately, not consistently miserable.

All of us are crazy in very particular ways. We’re distinctively neurotic, unbalanced and immature, but don’t know quite the details because no one ever encourages us too hard to find them out. An urgent, primary task of any lover is therefore to get a handle on the specific ways in which they are mad. They have to get up to speed on their individual neuroses. They have to grasp where these have come from, what they make them do – and most importantly, what sort of people either provoke or assuage them. A good partnership is not so much one between two healthy people (there aren’t many of these on the planet), it’s one between two demented people who have had the skill or luck to find a non-threatening conscious accommodation between their relative insanities.

The very idea that we might not be too difficult as people should set off alarm bells in any prospective partner. The question is just where the problems will lie: perhaps we have a latent tendency to get furious when someone disagrees with us, or we can only relax when we are working, or we’re a bit tricky around intimacy after sex, or we’ve never been so good at explaining what’s going on when we’re worried. It’s these sort of issues that – over decades – create catastrophes and that we therefore need to know about way ahead of time, in order to look out for people who are optimally designed to withstand them. A standard question on any early dinner date should be quite simply: ‘And how are you mad?’

The problem is that knowledge of our own neuroses is not at all easy to come by. It can take years and situations we have had no experience of. Prior to marriage, we’re rarely involved in dynamics that properly hold up a mirror to our disturbances. Whenever more casual relationships threaten to reveal the ‘difficult’ side of our natures, we tend to blame the partner – and call it a day. As for our friends, they predictably don’t care enough about us to have any motive to probe our real selves. They only want a nice evening out. Therefore, we end up blind to the awkward sides of our natures.

On our own, when we’re furious, we don’t shout, as there’s no one there to listen – and therefore we overlook the true, worrying strength of our capacity for fury. Or we work all the time without grasping, because there’s no one calling us to come for dinner, how we manically use work to gain a sense of control over life – and how we might cause hell if anyone tried to stop us. At night, all we’re aware of is how sweet it would be to cuddle with someone, but we have no opportunity to face up to the intimacy-avoiding side of us that would start to make us cold and strange if ever it felt we were too deeply committed to someone. One of the greatest privileges of being on one’s own is the flattering illusion that one is, in truth, really quite an easy person to live with. With such a poor level of understanding of our characters, no wonder we aren’t in any position to know who we should be looking out for.

2. We repeat unhealthy patterns from childhood, always latching on to people who will frustrate us in familiar but grievous ways

We believe we seek happiness in love, but it’s not quite that simple. What at times it seems we actually seek is familiarity – which may well complicate any plans we might have for happiness. We recreate in adult relationships some of the feelings we knew in childhood. It was as children that we first came to know and understand what love meant. But unfortunately, the lessons we picked up may not have been straightforward. The love we knew as children may have come entwined with other, less pleasant dynamics: being controlled, feeling humiliated, being abandoned, never communicating, in short: suffering. As adults, we may then reject certain healthy candidates whom we encounter, not because they are wrong, but precisely because they are too well-balanced (too mature, too understanding, too reliable), and this rightness feels unfamiliar and alien, almost oppressive. We head instead to candidates whom our unconscious is drawn to, not because they will please us, but because they will frustrate us in familiar ways. We get together with the wrong people because the right ones feel wrong – undeserved; because we have no experience of health, because we don’t ultimately associate being loved with feeling satisfied.

- — We fail to explain our feelings to our partners – because we don’t understand ourselves well enough. We act out our feelings rather than spell them out, often to destructive effect. (we break the door rather than explain we are mad with anger).

- — We are unaware of the effects of our words on others. We don’t notice how often we say critical things to them.

- — We can’t anticipate and signpost our feelings: when we start to get over-excited and talk too fast, we should know it’s time to go for a walk round the block because otherwise there’s liable to be an explosion…

- — We project, that is, we respond to events in the here and now according to patterns laid down in childhood; in our heads, our partners become mixed up with other people from our emotional history (a humiliating mother, a distant father etc…).

- — We’re governed by the past: old unfortunate habits keep their grip. We don’t see what’s happening and so we can’t do anything about it.

There’s a lot we can do once people are able to tell us what’s problematic about themselves. We don’t need people to be problem free – we need people to be able to explain where the problems are.

WORK

We only have a few short years in which to come up with a convincing answer about what we want to do with our lives. Then, wherever we are in the thought-process, we have to jump into a job in order to have enough money to survive or appease society’s demands for our productivity.

Without self-knowledge, we are too vague about our ambitions; we don’t know what to do with our lives and – because money tends to be such an urgent priority – we lock ourselves into a cage from which it may take decades to emerge.

- — We are too modest: we miss out on opportunities: we don’t know what we are capable of.

- — We are too ambitious: we don’t know what we shouldn’t attempt. We lack a clear sense of our limitations, wasting years trying to do something we’re not suited to.

- — We don’t grasp the ways in which we are difficult employees or bosses. We might – among other problems – be crazily defensive, or resistant to trusting anyone or too eager to please.

- — We don’t perceive our hidden attitudes to success and failure. It may be that we see ourselves (wrongly) as not cut out for the bigger roles or when things start to go well, we become manically prone to make a blunder. Perhaps we’re unconsciously trying to avoid rivalry with a parent, or a sibling by tripping ourselves up. Family dynamics have an enormous, subterranean influence on how effectively we operate at work.

LIVING WITH OTHERS

Without self-knowledge, we are, in general, a liability to be around:

- — We don’t realise the effect we tend to have on other people: without at all meaning to, we might come across as arrogant or cold, or as tending to hog attention or as needlessly shy and hesitant or as getting furious in dangerous ways.

- — We may fall prey to unnecessary loneliness: not understanding what we really need and what makes us hard to get to know.

- — Difficulties of empathy: not acknowledging the more vulnerable or disturbed parts of oneself; means not seeing oneself as being ‘like’ other people in crucial ways. It’s hard to understand the deeper bits of others without having explored oneself first.

SPENDING MONEY UNWISELY

Most of what we spend money on is a hunch about what will make us happy. But without self-knowledge, we’ll have a hard time figuring out the relationship between what we purchase and how we feel.

- — Holidays and travels will leave us disappointed.

- — Impulsive purchases will soon be regretted.

- — We’ll be prey to fashion: not knowing ourselves, we’ll be at the mercy of what consumer society tells us to want.

- — We might become inadvertent snobs: liking things because others like them rather than for deeper personal reasons.

Self-knowledge has always been important. But now it’s more so than ever. This is a result of political and social progress. When life was much more constrained by tradition, rigid social hierarchy and rigorous codes of manners, there was less need for self-knowledge to guide action. Now, if we are to exploit the independence and freedom we’ve been offered (in love, work and social lives), there is all the more reason to get to know ourselves in good time.

2. WHY IS SELF-KNOWLEDGE SO HARD TO COME BY?

We pay a high price for lack of self-knowledge. So why is it in short supply? Why is it hard for us to know ourselves in these ways? It’s not laziness or stupidity that explains it. There are several huge cognitive frailties that make it hard for us to have certain kinds of insight about ourselves. There are seven reasons why self-knowledge is tricky for creatures with the kinds of minds we have.

i. The Unconscious

Human beings have evolved into creatures whose minds are divided into conscious and unconscious processes. Digesting lunch is unconscious; reflecting on what you’d like to do this weekend is conscious.

The reason for this division is bandwidth. We simply couldn’t cope if everything we did had to be filtered through the conscious mind.

Also, we start off as children with fierce difficulties around self-awareness. Nature has structured us so that self-awareness comes very late on: you only have to study how children are to know that an awareness of self is a very late evolution of character.

In general, we can argue that we suffer because a little too much of how we behave happens unconsciously – when we would benefit from a closer grasp on what was going on. The default balance between conscious and unconscious tends to be wrong, we are incentivised to let too much of who we are happen in the unconscious.

As a general point, we need to make heroic efforts to correct the imbalance and bring more of our lives into the conscious realm.

ii. The Emotional and Rational Mind

A traditional way of conceiving of our minds is that there’s a small rational bit and a far larger, more dominant emotional bit.

Plato compared the rational bit to a group of wild horses dragging the conscious mind along.

Nowadays, neuroscientists tell us about three parts of the brain:

- – The reptilian

- – The limbic

- – The neocortex

The reptilian is, as the name sounds, the earliest and the most primitive. It’s interested in basic survival and responds immediately, in knee-jerk ways, unconsciously and rather aggressively and destructively. It’s what’s engaged if a lion surprises you in the jungle.

The limbic part of the brain, a later development is concerned with emotions and memories.

The neocortex, a very late development, is where our higher reasoning faculties lie.

We don’t have to buy into the precise terminology here to understand the drift: a lot of our lives is dominated by automatic, over-emotional, distorting responses by the ‘lower’ parts of the mind; and only occasionally can we hope to gain rational perspective through our higher faculties.

iii. Freudian Resistance

However, it isn’t just the case that things are unconscious by accident. It was Sigmund Freud’s great insight that they remain unconscious because of a squeamishness on our part: there is – in his term – extraordinary ‘resistance’ to making a lot of our unconscious material conscious.

The unconscious contains desires and feelings that deeply challenge a more comfortable vision of ourselves. We might discover – if we got to know ourselves better – that we’re attracted to a different gender, or have career ambitions quite different from those our society expects of us. We therefore ‘resist’ finding out too much about ourselves in many areas. It shatters the short-term peace we’re addicted to.

But, of course, for Freud, we pay a high price for this. Short-term peace is unstable, it is, to use another word of his, ‘neurotic’, and cuts us off from the benefits of long-term honesty about aspects of our identity.

Too often we say of thoughts, it’s ‘safer not to go there’. One simply pushes feelings and ideas aside. Resistance means we are escaping the humiliation of admitting to particular appetites and desires – especially when these are at odds with what we’d like to be like or how others want us to be. We reduce our immediate suffering. But the cost is that we can’t properly aim for what would truly make us happy.

iv. Other People Won’t Tell Us

There are many aspects of our identities that it is simply hard for us to see without the help of another person. We need others to be our mirrors, feeding back their insights and perspectives on the elusive, hard-to-see parts of ourselves.

However, getting hold of data from others is a very unreliable process. Very few people can be bothered to undertake the arduous task of giving us feedback.

Either they dislike us too much and therefore can’t be bothered. Or they like us too much, and don’t want to upset us.

Our friends are too polite; good intentions lead them to keep their less pleasant observations to themselves. Our enemies have so much to tell us: it’s not always the people we like who see certain aspects of us most clearly. It might be someone we’re at loggerheads with who has the sharpest sense of what’s not quite going right in our character (a way, for instance, of letting people down after a long period of seeming to go along with their plans; a very annoying habit of sitting on the fence). But they are not likely to be good at sharing their wisdom with us. They either won’t take the trouble, or will brush us off with the sort of sharp insults that will make us defensive and closed to the wiser aspects embedded within their harsh assessments.

v. We Haven’t Lived Enough

Many bits of self-knowledge only come through experience. Think of ourselves as being like a biscuit mould: it’s only by pressing ourselves against the dough of life that we get to see what shape we actually are.

Self-knowledge therefore isn’t something we can always do in isolation, retreating from the world to look into ourselves.

We acquire knowledge dynamically, by trying things out and colliding with others – which always carries a risk, and takes time.

In careers, for example, we can’t know what we might want to do with our lives simply by asking ourselves this question. We need to head out into the workplace and try things out. We need to spend a week at an architect’s office, or go and meet someone in the diplomatic service etc.

Self-knowledge can only evolve as a result of dialogue with the world.

vi. We Are Fatefully Vague About Stuff

Our thoughts about many things are marked first and foremost by vagueness. Our intellectual muscles are – by nature – rather weak. Our initial reactions to things are frequently of the order of ‘yum’ or ‘yuk’. We have pronounced pro or contra feelings towards something but struggle to say more. We say things like:

- — I want to be creative

- — I loathe big business

- — I’m feeling out of sorts

- — He annoys me

These reports might be true, but they are not very high-quality items in terms of self- knowledge. They’re not accurate enough to help guide action. It’s not that they are wrong, the problem is they are too vague. They don’t get to grips with what is really the issue. They circle in the big, general territory but don’t land anywhere specific.

This isn’t a personal problem. It’s universal. The first reports from our conscious minds are just by nature horribly vague – and in need of sustained analysis.

vii. Introspection is Low on Prestige and Unfamiliar

Introspection is the name we give to the close study of one’s feelings and ideas.

Unfortunately, it isn’t given high prestige in our society. We’re rarely encouraged to unpack our thoughts. The notion of what it means to have a conversation with a friend rarely includes trying to make progress in sorting out feelings. Psychotherapy – the prime arena for analysing oneself – interests barely 1% of the population.

Part of increasing the self-knowledge of a society is to help make the idea of introspection a little more glamorous; it should be thought of as a very plausible concept to spend a weekend on or host a dinner party around.

3. HOW TO GET MORE SELF-KNOWLEDGE — AND IN WHAT AREAS

RELATIONSHIPS

i. Repetition Compulsion

We’re not terribly flexible when it comes to falling in love. We have types. There are patterns: each of us tends to have a characteristic sort of person we go for – a more or less sketchy template of the sort of person we find very attractive.

The template is highly individual, but if we could open up people’s heads we might find things like:

The Byronic type — dark hair (frequently tousled), reserved but intense; naughty

The serene type — calm, unruffled, angst-free

The cheeky type — bouncy, unpretentious, free

We’re used to seeing our types in terms of the positives. But, in fact, every type also carries a lot of negatives as well. The people we tend to go for may be attractive to us not only for some very nice reasons but also because they bring with them some special kind of trouble or difficulty to which we are especially prone. Most of us are involved in the compulsion to repeat kinds of suffering in our personal lives, normally based on a suffering in early childhood.

Putting the same templates in darker terms, it might turn out that someone is drawn to:

A chaotic, selfish, volcanic person who seems always to be on the verge of losing their temper and is never on time (Byronic).

Someone who will be wrapped up in themselves and slightly depressed (serene).

An infantile person with poor self-management skills who needs a lot of looking after (cheeky).

We need self-knowledge in love because were so prone to repeat unhealthy patterns. We leave a relationship hoping to leave behind a particular set of problems – which we find again in the next relationship. These patterns normally derive from childhood experience whereby love was mixed in with various kinds of suffering. The father whose attention and affection we craved was also often annoyed (annoyance, ever since, has proved desperately interesting to a part of us); the mother who we loved was often preoccupied and always heading out to do more exciting things while leaving us behind (our partner is in a high stress job and doesn’t often call…)

Now when we’re searching for affection and closeness we look out for some quite negative, even damaging things, since we have learned to think that this is how love works. We don’t notice it, so the pattern keeps on guiding our behaviour in unfortunate ways. The psychoanalytic theory of repetition compulsion means that you’re also being drawn to something problematic. For example:

- — They are rather bossy

- — They are critical

- — They are in some way rather inadequate and in need of help

- — They are agitated and irritable<

Self-knowledge means first of all seeing the pattern. It means understanding the negative aspects of the type of person we tend to get involved with.

Culturally we are resistant to this kind of self-knowledge. We’re not used to the notion that we might be drawn to people for bad reasons. We want to say: I hate it when people don’t listen or I really don’t like irritable and agitated individuals. And of course that is true. We don’t like it when people behave these ways.

But we do much too often end up with them!

Exercise

Think of a celebrity or actor that you find attractive.

- – What are some good things you find attractive about them?

- – What might be the bad reasons you are drawn to them?

- – What are the difficult sides of people you’re oddly rather drawn to?

- – Sketch a ‘type’ you find attractive.

- – What are the bad reasons you find this type attractive?

- – What have the consequences been in your life?

Gaining self-knowledge about the darker aspects of one’s own pattern of attraction allows us to be more strategic.

When looking for a new relationship:

- — Realise that emotional appeal is not necessarily – for us – the best guide to who we could have good relationship with.

- — Pick up at a much earlier stage that one might be making this mistake and recognising that it is a mistake.

In a long-standing relationship:

- — Accept that we shouldn’t simply blame the other person for certain annoying characteristics – such as their distance or irritability. We can admit that this was part of what drew us to them in the first place.

- — It helps identify the kind of compensating maturity one needs; if you are drawn to quite critical people, you can’t always then blame them for being critical.

ii. Projection

Our minds have a strong natural tendency to projection, that is, to elaborate a response to a current situation from incomplete hints – drawing upon a dynamic set up in our past and indicative of our unconscious interests, drives and concerns.

Take a look at this image, which appears as part of a famous projection test:

If you ask, what’s going on here, we all could read different things into the image. People might say something like:

- — It’s a father and son, mourning together for a shared loss, maybe they’ve heard that a friend of the family has died.

- — It’s a manager in the process of sacking (more in sorrow than in anger) a very unsatisfactory young employee.

- — I feel something obscene is going on out of the frame: it’s in a public urinal, the older man is looking at the younger guy’s penis and making him feel very embarrassed.

One thing we do know – really – is that the picture doesn’t really show any of these things. It is an ambiguous image.

The picture simply shows two men rather formally dressed, one slightly older. The elaboration is coming from the person who looks at it. And the way they elaborate, the kind of story they tell, may say more about them than it does about the image. Especially if they get insistent and very sure that this is what the picture really means. This is projection.

We don’t just do this around images; the same thing happens with people. In relationships, projection kicks in when there are ‘ambiguous situations’.

For instance, your partner is quietly chuckling at a text message. They don’t offer to share it with you. They quickly send a reply. You start to feel very agitated. It looks like your partner is having an affair. They have just received a message from their lover reminding them of some very intimate joke (which might even be about you and your failings); you partner eagerly responds. They don’t love you. You are abandoned, betrayed. You are now very angry with you partner; you feel victimised. But actually, nothing like this is really going on at all. The message was from an over-conscientious colleague at work, and your partner found it comic they should be bothering about such trivia and didn’t think it was even worth mentioning. In fact, the distress you felt derived from when you were at school: you discovered that the person you thought was your best friend was actually saying mean things about to others. You are still wounded by this, though you hate to admit it.

The structure is

- — We observe something but in honest truth it’s not entirely clear what it means.

- — We read into the situation a set of motive, intentions, attitudes – which are usually distressing to us and give rise to anxiety and anger.

- — The anxiety or fear actually relate to an earlier experience. But we don’t realise this.

- — We are frightened by, or angry about, what’s happening now. Even though really we shouldn’t be.

Projection is always about telling ourselves a story in answer to the question: what did that really mean? That might be, for instance, be a situation as well as a person.

When we are projecting it doesn’t FEEL as if we are doing anything complicated or special. On the contrary it feels just as if we are seeing things as they are. So, typically we dislike the suggestion that we are ‘projecting’. It feels as if it is an insult to our ability to perceive how things really are. Admitting the possibility that one might be projecting is humbling. But it could be worth it because projection brings a lot of trouble into our lives. We’re venting our anger on the wrong individual. And maybe in the process hurting someone very unfairly. We are afraid of the wrong person. Our fear of someone in the past gets in the way of making a friend or ally of someone today.

Self-knowledge means recognising one’s projections and attempting to repatriate. The active issue isn’t here and now: it’s some unfinished business from the past that’s still bugging us.

Exercise

In the images below what do you think is going on?

– Say (without thinking too much) what you believe is happening. Write it down on a piece of paper, while others do the same.

– Then, as a class, go around and compare.

– Then ask yourselves what your possible explanation says not about the picture – it’s ambiguous – but about you. What parts of you have ‘projected’ into the ambiguous image?

ii. Confrontation and Criticism

Another area where a lack of self-knowledge bites is around how we characteristically behave with others, friends, family and colleagues. There are a number of themes here.

i: Confrontation Styles

Daily life offers us constant frustrations where we have a choice as to how we might respond. All of us exhibit a variety of ‘confrontation styles’, but we’re often unaware which kind we generally go in for – and what the costs and consequences are.

EXERCISE

Imagine that:

– Someone promised you a document by midday. It’s now 1pm.

– It’s your birthday next week, but your partner hasn’t said anything about it. You’d ideally love to go out.

– There’s a drilling sound coming from next door – again.

– A work colleague has been muscling in on one of your clients.

How do you feel? And how would you typically react?

There are 4 key varieties of possible responses: passive, aggressive, passive-aggressive or assertive:

- — PASSIVE: You feel it’s just how life goes, some things you have to accept; if you make a fuss, it just makes everything worse. After all, it’s not that bad really. Sometimes you really resent these things, but you make yourself put up with them.

- — AGGRESSIVE: “I’m bloody annoyed. Where is that document? Why hasn’t my partner mentioned a party? Why should I suffer because the neighbours are incompetent, stupid, greedy or too lazy to do their DIY at some reasonable hour? If they don’t get their act together you’re really going to show them who’s boss.” They can shape up or ship out as far as you are concerned.

- — PASSIVE-AGGRESSIVE: A curious toxic mixture of passivity and more aggressive feelings. One tells oneself things like: ‘I don’t make a big fuss about my birthday – and of course my partner has a lot on their plate always.’ But secretly one is fuming. Or one thinks, ‘X is a perennially unreliable fool,’ but when their document eventually comes in at 5pm, one says, ‘Great to get this!!’ and leaves it at that… There’s a lot of hostility around but it is indirect. The passive aggressive person keeps their anger veiled just enough so as to be able to deny it to others and to themselves. They don’t feel they are being negative or aggressive. They see themselves as hard done by. What they hate most of all is to make a fuss – but that doesn’t prevent them being very upset. Often, the upset which hasn’t emerged with the person who caused it will later find a way out with a more innocent party. Passive aggressive people who didn’t make their feelings clear in the office will, when they get home, frequently take it out on the kids, the partner or the dog. Passive-aggression has its roots in low self-esteem. One simply doesn’t feel one is allowed to make a direct critique. Direct criticism takes confidence. At the same time, one can’t be happy either. Therefore, the compromise is a veiled compromise attack.

- — ASSERTIVE: you are clear about when someone has behaved badly towards you or is causing a problem. You aren’t happy about it. But your main aim is to fix the problem. You don’t need to take revenge or try to get the other person to feel guilty. You can go up to them and confidently make your point. You aren’t ashamed of yourself or guilty for making a fuss. You think it’s normal to treat people well – you do – and if someone else falls below your standards, you’re not embarrassed to tell them so in plain terms. It won’t be a catastrophe, just a few unpleasant moments, but that will allow the relationship to improve over the long-term. No festering wounds here.

Very few of us are assertive. One estimate is that no more than 20% of the population manage to be direct in a mature way about their ailments. That means there’s a lot of subterranean anger, a lot of people who are being shouted at even though they aren’t really responsible.

The reason why passive-aggression is something we’re not aware of doing – and therefore need to increase our self-knowledge around – is that there are lots of inhibitions to being ‘straight’ around things one’s annoyed about:

– One might feel one doesn’t deserve to make a fuss.

– One might have a sense of shame/inner conviction of being bad which prevents one from taking the high ground ever, even when one deserves to.

– One might feel that other people will respond volcanically and catastrophically if one makes any complaint against them.

These assumptions are all worth questioning.

EXERCISE

This is from something called the Ascendance-Submission study by the American psychologist Gordon Allport:

1. Someone tries to push ahead of you in line. You have been waiting for some time, and can’t wait much longer. Suppose the intruder is the same sex as yourself, do you usually:

– Remonstrate with the intruder

– ‘Look daggers’ at the intruder or make clearly audible comments to your neighbour

– Decide not to wait and go away

– Do nothing

2. Do you feel self-conscious in the presence of superiors in the academic or business world?

– Markedly

– Somewhat

– Not at all

3. Some possession of yours is being worked upon at a repair shop. You call for it at the time appointed, but the repair man informs you that he has “only just begun to work on it.” Is your customary reaction:

– To upbraid him

– To express dissatisfaction mildly

– To smother your feelings entirely

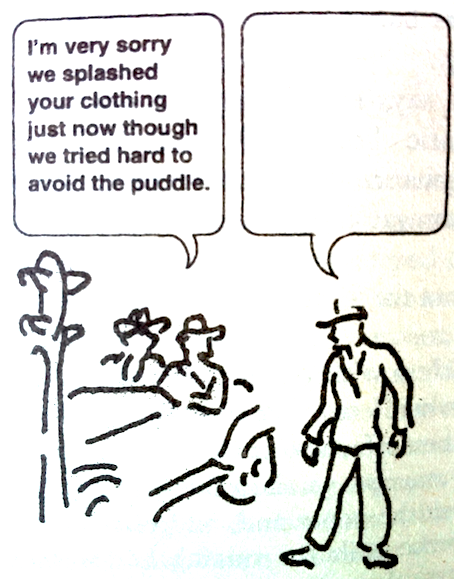

Another American psychologist, Dr Saul Rosenzweig, came up with the Picture Frustration test, which shows a number of frustrating situations and invites us to fill in the blanks:

How might you respond to this scenario?

Try this out + discuss what other moments in life you respond in similar ways…

ii: Criticism

Criticism is always challenging, but people respond to it in a variety ways.

It can be hugely beneficial to get a better grip on your characteristic response/behaviour around criticism – in order to be able to modulate it, and advance towards the more mature varieties.

Possible Responses to Criticism

1. They must be entirely wrong:

This is the response colloquially known as ‘defensive’ – whereby a criticism unleashes a disproportionately strong defence against it. The original criticism isn’t heard, for its destinee is so taken up with shoring up their position.

One thinks: “I am OK, I don’t generally make mistakes. If they are annoyed with me, it’s likely that they are being too demanding, or they’re jealous, or they’re trying to kick me down. The problem is theirs.”

2. They must be entirely right and I don’t deserve to exist:

Here one thinks that a local criticism (of a book, a document, something one said over dinner) is in fact pointing to a global problem. Very quickly, the local criticism brings about a crisis:

“I don’t deserve to exist. I am a wretch. They have seen through the facade. It is true, I am meaningless, petty, stupid and dull…’

3. They might be right AND I can be OK

Here one is able to contain the criticism to the issue at hand. One is able to distinguish between a criticism of some aspect of oneself and a wholehearted assault on one’s identity.

Exercise

One of the most popular forms of self-knowledge exercises among psychologists involve an invitation to finish sentence stubs.

The idea is to answer fast, without thinking too much, thereby allowing the unconscious mind to have its say before it is censored.

Here are some sentence stubs to complete around the issue of criticism:

– When someone points out a piece of work of mine is less than perfect, I…

– When my boss says something to me, I think…

– Bosses who criticise typically…

Try to work out your Criticism style:

– are you defensive

– or do you feel globally attacked

– or locally attacked?

Analysis

One’s response to criticism is formed in childhood.

It is the task of all parents to criticise their children and break bad news to them about their wishes and plans – but there are evidently different ways of going about this.

The best sort of criticism leaves a child feeling that the criticism is local – but that they remain loved and adored.

Moreover, the suggestion is that everyone makes mistakes, especially the parents, and that criticism is a well-meaning and in no way threatening aspect of daily life.

But there are also scenarios where the child is criticised and no one notices that the criticism cuts too deep. There is no suggestion that this is ONLY a limited criticism. The child falls prey to the belief that they are entirely worthless. Throughout adulthood, the slightest critique can re-evoke this perspective.

Discussion

What did you learn about criticism in your childhood?

How did your mother/father make you feel when they criticised you?

iii. Career

i: Vagueness around one’s ambitions

When thinking about aspirations, hopes and what it would be good to do, there’s a very strong tendency to end up saying things like:

- — I want to help other people

- — I want to be creative

- — I want to do something that matters

The statements might be very true and the sentiments admirable. The problem with them is that they are vague. They don’t point in any particular direction: they don’t guide action or do much to help make a decision. Vagueness is a sign of the difficulty we have around self-knowledge. It shows that in some important aspect of life we don’t yet know ourselves very well.

How do we improve self-knowledge around ambitions?

Exercise

1. Dare to name some people you envy and or admire – however grand and implausible. One of the causes of vagueness is that (after the age of about eleven) we feel embarrassed to mention very high status individuals as inspiration; we sense that we’ll be seen as pretentious or naive. But it’s important to list them because they are the grandest version of the person you want to be. It could be Michelangelo or Lady Gaga or Goethe or Bill Gates. The point isn’t that you necessarily want to be them or just like them. It’s that there is something about them that you want to learn from.

2. Moving from person to trait. Analyse what it is about them that you admire…

It needn’t be the thing they are most famous for. The cause of vagueness here is that we get hung up on people. We focus on the person – and there are so many different things about them that are impressive. So simply naming them leaves it vague what it is we’re trying to learn from this person’s example.

3. How could that quality be more present in your life…

Another cause of vagueness is inflexibility. We can see how that quality played itself out in that person’s life. But what we really want to know is what else can be done with it. The person we’re thinking about is only giving a hint.

ii: Attitudes to ambition

There are many obstacles to doing well at work, getting the kind of partner we feel we deserve; or getting on top of our financial and creative lives: competition from able rivals, not enough room at the top, prejudice, limited talents. But some of the most serious barriers to success come from within our own heads. We suffer from problematic attitudes to success.

We are held back by anxiety around success. These anxieties mean that we are not purely seeking to succeed. Without realising it, we are also quite invested in aspects of failure.

— Success makes you envied. They’ll think I’m showing off, big-noting myself. I really don’t want to be the target of other people’s envy. Better to remain on the sidelines.

— Inner feudalism: there are sorts of people who are allowed to succeed and do big things in the world; unfortunately, I’m not one of them; things like that just don’t happen to people like me.

There is also the danger of over-investment in the idea of ‘success’. It’s natural to want to do well-enough around work. But career can be a magnet for other hopes that don’t really belong in this area. One comes to believe that if only things go well in terms of career or money, many other problems will be solved too. It’s a line of thought that is strongly encouraged by contemporary society. Meritocratic attitudes invite the misleading thought that how you do at work is a measure of your global worth; advertising relentlessly projects the thought that psychological qualities like friendship, good relationships, serenity and a sense of fun are tied to financial prosperity (and hence to career success). These kinds of thoughts are not explicitly running through our heads but reflection on our behaviour may indicate that we act as if we believe such things as:

“If I succeed at work, I will deserve to be loved.”

“I will stop feeling lonely when I’ve made it.”

“The holiday will be great – if only we stay in luxury.”

“High status means happiness.”

Once such beliefs have been made explicit they can be put to the test. For instance: other people can succeed, but not me. Is it true? Examine it like a statement in court. What evidence supports this? What are all the things that could be said in its favour and assess their plausibility.

— Some people are born lucky – this can’t be right.

— Talent is unequally distributed – true, but many of the people who you think are successful are not more talented than you.

— There are prejudices which favour some and disadvantage others – yes, but (usually) only to some extent, they are not decisive.

Exercise

— If I succeed, what will happen is… (both negative and positive)

— By succeeding, I’d love to please…

— The person who might (secretly) be most dismayed by my success would be…

— People who are successful are typically…

— I wouldn’t want to be a success because..

iii: The meaning of your life

In the middle of daily life, impressed by the expectations of other people and bombarded with ideas from the media and advertising (which are unlikely to have one’s own best interest at heart), it’s completely unsurprising that we get confused about how much something really matters to us.

Exercise

If you were on your deathbed, what would you regret not doing…

The exercise is designed to tease out underlying ambitions that you are reluctant to explore. They might seem too challenging or embarrassing to admit to anyone else. The point isn’t necessarily to explain them to others but to give them more attention in the privacy of your own head.

- Why, in fact, do you hold back from doing these things?

- How might those obstacles be addressed?

- What specific practical steps you could take?

The death-bed exercise also helps reveal the true hierarchy of our needs.

- Things that have only a very limited contribution to make to our flourishing come to seem much more important than the really are.

- We underrate the importance of things that are familiar or maybe not especially exciting.

iv. What Others Can Know of Us

When it comes to other people, we are all a bit like mind-readers. Mind-readers astonish their customers by telling them things about their lives – you have had a quarrel with your parents recently; you were close to a sibling when you were a child, but in recent years you have drifted apart and that makes you sad. And the visitor is left wondering: how did they know this about me. It must be magic. They can sometimes tell us after a minute things that it’s taken us years to find out about ourselves. They might note that we react defensively when mentioning our parents – as if we feel we are about to be accused of something; though this characteristic is one we are reluctant to recognise in ourselves. Mind-reading just shows up that knowledge about us is surprisingly obvious and easy for an outsider to get hold of – much easier than for us inside. Strangers are surprisingly good at guessing things about us.

One consequence is that we find it difficult to grasp how other people see us. The gap between self-perception and the point of view of others is richly comic: pomposity for example occurs when someone can’t see that other people don’t share their high opinion of their own merits; and there’s a satisfaction in seeing this person being forced by events to a much lower and more accurate picture of themselves. But mostly, of course, it doesn’t seem especially funny:

You don’t realise

— That you are taxing other people’s patience

— Other people often feel you hog the limelight

— You come across as arrogant

— You seem excessively diffident

— You are often trying to hint that you have done everything anyone else has done; as if it would be painful to you to be impressed by anyone

The point isn’t that other people are always right. The point isn’t that one should feel cross with other people for not rightly appreciating one’s better intent. (‘Of course, I didn’t mean to be arrogant? Can’t they tell the difference between honest assertion and showing off?’) It’s just that it is really helpful to know how we impact on other people since this allows for strategic adjustment. Once we know we can try to change for the sake of getting on better with others – being a little less assertive at certain points or making an effort to ask other people questions about themselves.

Exercise

Pair up with someone.

Get them to say 5 nice things about this person, based on very little knowledge.

Then, one negative thing.

How did they know this negative thing?

Swap roles.

Exercise

– Write down the kind of animal you might see yourself as being. And list three attributes that you feel you share to some extent with this kind of creature.

— Then ask another person to draw the animal they see you as being, and to pick out three characteristics that help explain why.

— What do you learn from their choice and their reasons?

v. Family Dynamics

i: Overall Picture: How you feel about your family

What do you really feel about your family? Especially the things that you don’t say for all sorts of reasons: you might hurt particular people; you feel guilty because, after all they have been very good to you in some ways; you feel disloyal; you fear that people will feel sorry for you in ways that make you awkward; you fear that people will regard you with contempt. Such thoughts are likely to remain shadowy. We have unconscious – or barely unconscious attitudes in relation to family that are liable to play serious havoc with our lives. Possibilities include:

>Attitudes to a younger brother are governing one’s feelings about never having enough.

>Feelings about an older sister have led to problems around envy.

>A general tendency to be deferential around authority might be traced to an excessive need to please one’s parents.

Exercise

A key psychological exercise is to draw your nuclear family; putting in parents + siblings + house + a sun + a tree.

Then examine the drawing.

Draw your family.

Ask: Who is big?

Who is small?

Where is everyone standing?

Some typical themes in analysis:

– who you draw yourself next to is who you are closest to.

– who are you are most distant from is put faraway.

– the size you have drawn yourself is the size of your self-esteem.

– the house is an extension of yourself: it is the ego. Is it in good shape? Optimistic? Ordered?

Windows imply a degree of communication/passage. Does it have a door?

This is only a start, and it’s not science – but the exercise is useful nevertheless, trying – like the sentence stubb exercise – to catch our unconscious slightly unawares in order to reveal its structure.

ii: Blame and self-knowledge:

We may not be aware of the extent to which we assign problems in our lives to our parents.

Exercise

1. What do you blame your parents for?

Here we are looking for an ego response: how they hurt me, the mistakes they made etc.

2. Why do you think they were the way they were?

This is a very different sort of question. It asks you to step outside of yourself and ask not, how did they hurt me or disappoint me – but rather, what were the pressures and difficulties they were under. It interrupts the circuit of hurt-blame, replacing it with hurt-understanding.

Blaming one’s parents isn’t – of course – always a mistake. It’s just that doing so can get in the way of a better understanding of the nature of a problem. And hence of what it is possible to do about it.

vi. Taste and your idea of happiness

We aren’t used to the idea that interior decoration can tell us anything very intimate about ourselves. But aesthetic preferences can yield revealing insights. That’s because personal taste reflects other things about us.

We may be disturbed by unfortunate associations to certain kinds of objects or environments. At a particular age you might have seen a film in which a character who deeply appealed to you, lived in rather grand classical mansion; ever since then you’ve had quiet – but quite strong – positive feelings about such places. Understanding the attraction leads back to the prior question: what it was about that character that you found so appealing? Or it may be that a rather fearsome relative was very critical of mess, which touched off a rebellious opposite in you; you find a bit of clutter and a confusion of colours homely and endearing (which that person definitely was not). Analysing the response helps uncover the further concerns – the loves, antipathies, hopes and fears – that helped to shape your taste.

We are drawn to things we don’t have enough of. Aesthetic preference is often connected to the pursuit of balance. If we are typically stressed and anxious, we might be very attracted to serene environments. A person who has been assailed too often by boorish people, might be very attracted to things that suggest refinement, order and harmony: the lack of which has been painfully brought home to them.

We find neglected parts of ourselves in objects: in daily life we may give little attention or respect to aspects of our own nature that – however – hint at their existence in our tastes. The thrilled response to a grand interior in another wise demure individual suggest a bolder, more ambitious side to them.

Exercise

Consider these different interiors:

ornate

baroque

bohemian

cosy clutter

minimalist

Which one do you hate?

Which one are you drawn to?

The underlying theory is that we are drawn to visual styles which capture what is MISSING in our psyches.

In other words, the person attracted to calm-minimalism doesn’t feel calm inside. They feel on the verge of being overwhelmed – and look to a taste that can CORRECT their inclinations.

Similarly with the bohemian style – this is favoured not by bohemians, but by people deeply frightened of their native impulses towards conformity and rigidity.

We use visual decoration styles to correct/rebalance ourselves.

vii. Wisdom and the Search for Moments of Higher Consciousness

Often, self-knowledge is concerned with describing more accurately how one feels. It follows the path of introspection. You try work out what you actually feel when you look at the sky or watch a film or feel bored in a meeting.

But there’s another side to self-knowledge: becoming more aware of how the self-machine works: of how your mind operates and distorts things. For instance, you learn that eating a lot of chocolate makes you feel a bit queasy afterwards. Eating chocolate doesn’t feel as if it will do that. It’s so delicious you can’t resist another square. But gradually you just learn that this is how your particular machine work: if you put in a lot of chocolate it starts to create problems. Just as we can learn how the body works, we can also learn how the mind works.

One of the major implication of evolutionary theory is that the human brain itself has evolved over a very long period of time. The body, we readily accept, carries many indications of its long, long developmental story. The kind of eyes we have, the way our knees work or how our lungs extract oxygen from the air are not unique to humans. These kinds of organs and joints evolved long before humans were around.

So too with our brains. Hence the usefulness of talking about a ‘reptilian’ part of the brain, even though it isn’t absolutely correct scientifically (we don’t literally have the brain of lizard encased within our skulls). We have instincts and response patterns that evolved to suit being chased by predators or needing mate no matter what, that are more suited to existence in the pleistocene era than to life in a modern metropolis (or rural farming community).

The reptilian brain is interested only in survival and responds instinctively and fast. It is out for itself, it has no capacity for empathy or morality. It is deeply and constitutionally selfish.

But we also have a more evolved mature brain (scientists call it the neocortex) which is able to gain a distance from immediate reptilian demands. It can observe rather than submit to the sexual impulse: it can study, rather than obey, selfish desires etc.

The picture of ourselves – as having a sophisticated mind sitting on top of a primitive one – is very helpful because it makes sense of some of our troubles and of our potential for addressing them. The primitive brain is very concerned with safety and reproduction. It is impatient. It’s violent in asserting itself. It has no interest in reasons and explanations. It cannot comprehend what an apology is. In some of our worst moments, the primitive brain is doing the work. From its point of view, smashing a glass on the table might be an ideal way of getting someone to agree with you; being insulting, aggressive and boorish might look like a great way of getting to have sex with someone.

That we can behave very badly is, therefore, entirely unsurprising. But it means also that such bad behaviour cannot possible be the whole story about us. Having a divided brain – a reptilian and non-reptilian mind – means that the task is always to get the higher part of the mind to be more in charge and to take over whenever things get complicated. If we understand this about ourselves than we don’t have to go around thinking that we are totally worthless and awful because we did a genuinely very stupid and pretty nasty thing. The evolutionary story gives a more helpful explanation. You are not thoroughly bad at all. You just have a current problem: your modern brain is not as strong as it needs to be – and your reptilian brain is far too strong.

It defines the nature of the task: I need to get my non-reptile brain to be more prominent. And I need to learn to distinguish which of my hopes, fears and desires belong to the reptilian mind – and which are soundly founded in the higher rationality of the more evolved mind.

What we can call higher-consciousness occurs as we flex the muscles of our modern brain; and manage to free ourselves from the hold of the reptilian brain, gaining perspective over our immediate impulses and moods.

In another kind of language, we’d say we had been able to ‘free ourselves’ from the ego and to survey our lives and the world free of the immediate imperatives of being ourselves.

There are FIVE key ways this happens.

One: Fostering a capacity to observe one’s cruder impulses

Very occasionally, perhaps late at night, when the pressures of the day have receded, we have access to what feel like moments of wisdom – they usually don’t last very long but for a short period of time we have access to crucial ideas or insights about the way we operate, which is free of the normal subjectivity, defensiveness or self-justification.

In the morning – and for pretty much the whole day – you are in a rush. At dinner, your partner makes a comment about how you eat too fast or how you tune out when they are talking about their work – and immediately you get defensive; you insist you don’t do these things, you say they are hypercritical, that they don’t care and are always coldly judging you. You are furious and might slam the door.

Then lying awake in the middle of the night you have a powerful sense that quite often you move too fast defend yourself whenever your partner says anything a bit critical. You can picture yourself doing it. They start to speak, it’s so familiar, and immediately you are crouching, ready to deflect the blow. And so you don’t really hear what they have to say. You admit – very, very privately – that you do quite often stop paying attention when they talk about work; it’s not merely that you have stopped listening to all the ins and outs of life in their office; it’s that you have stopped paying attention to the way they are speaking, to what it means to them and why.

So, they’ve got a point. But you feel compelled to say they don’t. And truth be told you know you do eat too fast. Yes, it’s annoying to have it pointed out. But you realise that being a bit critical is a way your partner tries to show affection and care; it’s a possessive gesture on their part. You want to say you’re sorry, hug them, do it differently. In the dark it all makes sense.

The midnight insight was right. It was a moment of self knowledge. It was a moment of ‘higher consciousness’ when it was possible to stand back from experience and see it more clearly. You felt sufficiently safe and calm to observe your own behaviour without rushing to either condemn or defend it. You became wiser about yourself.

Such states of mind are, however, intermittent. Most of the time we have to be very intent on defending our patch, on fighting our cause. We lack the calm to observe our primitive mind in action.

Two: Developing a capacity to interpret the behaviour of others, rather than merely react to it automatically

Most of the time, we respond immediately (and rather powerfully) to the behaviour of others.

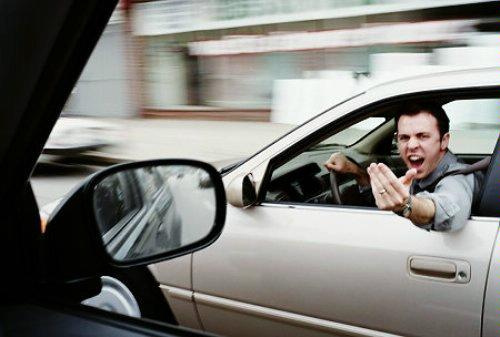

They honk the horn at us, we get furious and honk back.

They say something mean-sounding, we insult them right back.

The natural instinct is to meet the primitive with the primitive. Our own reptile nature wants to attack their reptile selves and beat them back into their hole.

But there is, of course, another option – one of the great marvels of evolution and civilisation (morality and religion too).

The civilised, higher move is to understand that they are behaving badly for a reason which they are in no position to tell you about, so under pressure are they from their more primitive minds.

Maybe they have had a hard day. Maybe they are worried about something. Perhaps they have felt squashed and sidelined in their career and now having someone squeeze in in front of them on the road is too much to bear. Instead of simply seeing them as the dangerous enemy, we can recognise that they are distressed and that their bad behaviour (the impatient horn the swearing behind the windscreen) is a symptom of hurt rather than of ‘evil’.

It’s an astonishing gradual evolution to develop the ability to do this – to explain other people’s behaviour as caused by their distress, rather than simply to see it in terms of how it affects us. There must have been a first time in human history this happened. And in each life there is perhaps a similar awakening. But often it is so hard for this higher consciousness to break through; we are so deeply caught up in our own troubles that we find it almost impossible to be generous in our assessment of why others are causing us trouble:

Try out these ideas (they sound foreign); they are examples of higher consciousness:

- the sales assistant is being curt with your request, perhaps because his relationship is breaking up. It isn’t about you.

- the snobbish person at the party is, ultimately, insecure (although they look self-confident and have just ignored you).

- the lout who scratches your car is terrified of being exposed as sexually inadequate.

- the boaster at the bar is convinced that he can never be loved.

Three: Developing a capacity for universal love

Once we are able to interpret someone’s pain-inducing behaviour as having roots in their own pain, we’re on the threshold of a remarkable steps. It then appears that in truth, no one in this world is ever simply ‘nasty’. They are always hurt – and this means that the appropriate response to humanity is not fear, cynicism or aggression, but love.

Once we relinquish our egos, and loosen ourselves from the grip of our primitive defensive and aggressive thought-processes, we are free to consider humanity in a much more benign light. We might even, at an extreme (this might happen only very late at night once in a while), feel that we could love everyone, that no human could be outside the circle of our sympathy.

We attain a state reported by certain yogis, christian ascetics and buddhist monks – wherein we feel that we have loosened ourselves from the self: we are looking at the world as if we were not ourselves, without the usual filter of our interests, passions and needs.

And the world, at that moment, reveals itself as quite different: a place of suffering and misguided effort, a place full of people striving to be heard and lashing out against others.

The fitting response is universal sympathy and kindness.

We have taken self-knowledge in a new and interesting direction. Being so aware of ourselves that we can remove the ‘lower self’ from the windscreen through which we look at things – and therefore look at things in a truer and unegoistic way.

For years you have had to fight your corner: you have had to grab at every opportunity, defend yourself, look out for your interests. You have to feed and clothe yourself, pay the bills, manage your education, deal as best you can with your own moods and demons. You have to assert your rights, justify your actions and your choices. Being alive is all there is. You are understandably obsessed with your own life – what option do you have?

But there are moments when one’s own life feels less precious, or less crucial – and not in a despairing way. And without the support of any imagined afterlife. It might be that the fear of not-existing is – if only for a little while – less intense. Perhaps looking out over the ocean at dusk or walking in woodland in winter, or listening to a particular piece of music Bach’s double violin concerto, that it would be alright not to exist; one can contemplate a world in which one is no longer present with some tranquility and still feel appreciative of life. In such rare moments of higher consciousness, one’s mortality is less of a burden; one’s interests can be put aside; you can fuse with transient things: trees, wind, waves breaking on the shore. From that higher point of view, status doesn’t seem important, possession don’t seem to matter, grievances lose their urgency; one is serene. If certain people could encounter you at this point they be amazed at the transformation.

These higher states of consciousness are short lived. We have to accept that. We shouldn’t aspire to make them permanent – because they don’t sit so well with many of the very important practical tasks that we need to attend to. We don’t need to be always in them. But we do need to make the most of them. We have to harvest them and preserve them so that we can have access to them when we need them most. The problem is that when we are in these higher states of mind we have highly important insights; but we lose access to them when we return to the ordinary conditions of life. And so we don’t get the benefit of the insight that was there in those special moments.

In the past, religions have been very interested in this move. The Christian churches, for instance, cottoned onto the fact that at times we can recognise that we have been unfair and disloyal to others. It’s a huge triumph over the primitive mind which has little time for such possibilities. They established rituals designed to intensify, prolong and deepen these fragile insights. There was, for example, highly charged words of a special prayer, the Confiteor:

I confess to Almighty God and to you my brothers and sister

that I have sinned through my own fault, in thoughts and in my words, in what

I have done and in what I have failed to do…

So that, ideally, on a very regular basis people would have a powerful experience of recognising that they might have been cruel, harsh, thoughtless, greedy or mean. It didn’t necessarily always work, of course, but the idea is highly significant. It’s an attempt to make this kind of experience less random. To give it more power in our lives and to make the best use of it.

The ideal, which is obviously separable from Christianity and involves not occult belief, is that the higher parts of the mind should be more reliable and more powerful.

Four: Developing a suspicion about your own feelings

Normally we are used to the idea of gaining self-knowledge by asking ourselves ever more closely: how do I feel about this?

The idea is that you know ‘who you really are’, by studying your feelings.

But this suggestion here is something different, indeed the opposite.

What we advise is a capacity to stand aside from feelings in order to recognise their potentially deceptive nature. It means acknowledging a fundamental distinction between what we might feel about a situation – and what it might actually be.

The classic example of this historically is when humans learnt for the first time to accept that even though the earth feels flat, it is in fact round. In other words, when humans learnt to be suspicious about their feelings, trusting instead to the data of their rational minds – overruling feeling for the sake of reason. This has come very very late on in human evolution, and in day-to-day life, most of us operate in a pre-Copernican way, especially as regards our emotional lives.

One exception though, from which we can learn a lot, is children. When we deal with small children, we rather easily override our reptilian responses and aim for a higher interpretation. We look beyond what seems, and try to picture what is.

Imagine a child who is whiny and then goes up to its parent and hits it and says, I hate you.

The primitive response is to hit back. The more sophisticated one is to ask: what is going on beneath what I can see of the child’s behaviour?

And, because it’s 6pm and they haven’t had a nap and had a bit of a cold, one will quite naturally ascribe the bad mood to these factors. The higher mind will have interpreted the situation.

However wise this might be, we find it hard to perform the exercise on ourselves.

We too might be feeling tired and hungry. But we don’t ask ourselves what role this might be playing in our sudden sense that everyone hates us and that our careers are a disaster.

These seem like entirely reasonable conclusions to draw from real facts. But, in reality, they are the outcome of a very tired and hungry mind trying to deal with existence. After a snack and a lie down, our views will be very different.

In other words, our minds are filled with ideas that seem to be rationally founded but actually are not, that owe much to lower physical processes that are denied or unrecognised.

Self-knowledge means becoming much better at realising how many of our mental processes (extending to things like our views on politics and our assessments of our careers and our lovers) can be explained by:

– not having drunk enough water

– not having had enough sleep

– lacking something to eat

If you haven’t slept well for a few nights and you’ve been working too hard, a few not too tactful comments from your partner can leave you considering divorce. It feels as if your relationship is in tatters, that you need to take a life-changing, dramatic and risky step; that the compromises, accommodations and love of the last few years have all been wasted. The problem looks enormous. But actually it isn’t. All that’s wrong is that you are tired. It’s shockingly hard for us to distinguish between a need of the body and a harrowing emotional conflict.

Or it might be that, having skipped breakfast, a tricky work meeting leaves you determined to resign. Things will be tough, certainly, but anything is better than continuing to sell your soul to these mindless fools. The problem looks as if it is huge – one’s career has taken a calamitous turn. Yet the real cause may be no more than depleted blood-sugar levels.

Being told that one’s view of existence is – at this moment – not the product of reason but of indigestion or exhaustion, is utterly maddening. Especially when it is true. We want to believe our woes are essentially all high flown – intellectual, moral and existential – when they are often no more, but also no less, than a disturbance of the body.

We should be careful of over-intellectualising. To be happy, we require big things (money, freedom, love), but we need a lot of semi-insultingly little things too (enough sleep, a good diet, a sunny sky). Babies know this well. They’re usefully unintellectual. They’re on hand to remind us of some profound truths.

The operative question, then, isn’t always ‘how do I feel?’ Self-knowledge might equally derive from asking: how do I function? What role are emotions playing in my life? And it can lead us, crucially, at times to discount them despite their strength. This is the higher capacity to stand aside from one’s feelings.

When you are tired, dehydrated or hungry, stressed or frightened these states of mind alter your perception of reality. The sense become misleading. Other people’s behaviour is liable to look more menacing than it is; we find it harder to grasp their more complex motives. Threats look bigger than they are; sources of security or pleasure look smaller, more fragile and more distant than in truth they are.

The higher position is to recognise that this is a way the self functions. This is what tiredness, dehydration and such states do to us. So we know to be suspicious of certain states of mind, we have to learn not to act on them. Wisdom means getting better at asking: is this reality or might I be seeing things in a distorted way, due to a lack of lunch or 2 hours less sleep.

PHILOSOPHICAL MEDITATION

ORDERING OUR MINDS RATHER THAN EMPTYING THEM

Even though our minds ostensibly belong to us, we don’t always control or know what is in them. There are always some ideas, bang in the middle of consciousness, that are thoroughly and immediately clear to us: for example, that we love our children. Or that we have to be out of the house by 7.40am. Or, that we are keen to have something salty to eat right now. These thoughts feel obvious without burdening us with uncertainty or any requirement that we reflect harder on them.

But a host of other ideas tend to hover in a far more unfocused state. For example, we may know that our career needs to change, but it’s hard to say much more. Or we feel some resentment against our partner over an upsetting incident the night before, but we can’t pin down with any accuracy what we’re in fact bitter or sad about. Our confusions sometimes have a positive character about them but are perplexing all the same: perhaps there was something deeply ‘exciting’ about a canal-side cafe we discovered in Amsterdam or the sight of a person reading on a train or the way the sun lit up the sky in the evening after the storm, but it may be equally hard to put a finger on the meaning of these feelings.

Unfocused thoughts are constantly orbiting our minds, but from where we are, from the observatory of our conscious selves (as it were), we can’t grasp them distinctly. We speak of needing to ‘sort our heads out’ or to ‘get on top of things’, but quite how one does something like this isn’t obvious – or very much discussed. There is one response to dealing with our minds that has become immensely popular in the West in recent years. Drawn from the traditions of Buddhism, the practice of meditation has gripped the Western imagination, presenting itself as a solution to the problems of our chaotic minds. It is estimated that 1 in 10 adults in the US has taken part in some form of structured meditation.

Adherents of meditation suggest that we sit very quietly, in a particular bodily position, and strive, through a variety of exercises, to empty our minds of content, quite literally to push or draw away the disturbing and unfocused objects of consciousness to the periphery of our minds, leaving a central space empty and serene. In the Buddhist world-view, anxieties and excitements are not trying to tell us anything especially interesting or valuable. We continuously fret without good purpose, about this or that random and vain thing – and therefore the best solution is simply to push the objects of the mind to one side.

Buddhist meditation has been so successful, we are liable to forget another effective and in some ways superior path to finding peace of mind, this one rooted in the Western tradition: Philosophical Meditation. Like its Eastern counterpart, Philosophical Meditation wants our thoughts, feelings and anxieties to trouble us less, but it seeks to sort out our minds in a very different manner. At heart, it doesn’t believe that the contents of our minds are nonsensical or meaningless. Our worries may seem like a nuisance but they are in fact neurotically garbled but important signals about how we should direct our lives. They contain complex clues as to our development. Therefore, rather than wanting simply to empty our minds of content, practitioners of Philosophical Meditation encourage us to clean these minds up: they want to bring the content that troubles us more securely into focus, and thereby usher in calm through understanding rather than through evacuation.

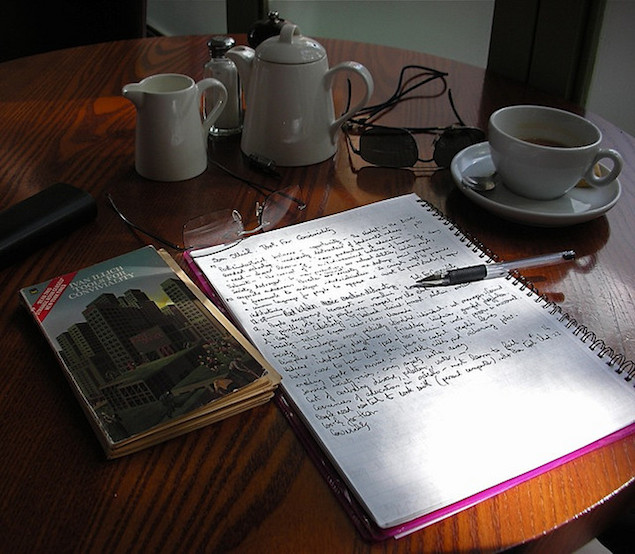

How does one bring the confused objects of the mind into focus? There are instructions for Philosophical Meditation, just as there are for Buddhist Meditation (a little artificiality in these matters may just be what we need to lend the process discipline). The first priority is to set aside a bit of time, ideally 20 minutes, once a day. One should sit with a pad of paper and start by asking oneself a very simple set of questions: what is it that I am regretful, anxious or excited about at present? One is invited to download the immediate contents of one’s mind. One will by nature be a little unsure of what our feelings mean, so it is best simply to write down – without thinking or censoring ourselves – one or two words around each feeling. It’s a case of tipping out the contents of the mind onto the paper as unselfconsciously as possible. One might, for example, write down: Darren, Cologne trip, weekend, shoes, Mum, face at train station… The task is then to try to convert each of these words from an ambiguous and silent worry, regret or thrill into something one can understand, grasp, order and eventually better control. Success in this meditation relies on a skilful process of questioning. Imagine these thoughts as ineloquent and muddled strangers, who are full of valuable ideas, but whom one has to get to know in a roundabout way, by directing just the right questions at them. [See the link at the end of this piece for a more complete Guide to Philosophical Meditation]

Philosophical Meditation brings us calm not by removing issues, but by helping us to understand them, thereby evaporating some of the paranoia and static that might otherwise cling to them. When confused objects of consciousness become clearer, they stop bothering us quite so much. Problems don’t disappear, but they assume proportion and can be managed. For example, we may make ourselves at home with an array of administrative worries that had been clumsily concealed under the vague title of ‘the Cologne trip’. The word ‘Darren’ might disclose someone we envy, but who holds out a fascinating run of clues as to how we might make a new move in our career. The word ‘weekend’ yields feelings towards one’s partner which are both resentful and yet capable of being discussed and perhaps worked through in the evening. Sorting out our minds doesn’t just feel comforting (like tidying our homes), it also spares us grave errors.

Confused excitement can be highly dangerous when it involves career ambitions. Imagine someone with a tendency to experience excitement when reading Vogue or Gourmet Traveller – and who then declares, without much attempt to analyse the feeling, that they want ‘to work in magazines’. It may seem reasonable enough for them to send off a CV to the magazine company HQ. After many efforts, they may be offered a lowly internship. It might take a few years and a lot of heartache before they realise that it wasn’t really the magazines themselves that were the true object of their attraction to begin with. Actually what was really speaking to this person was the idea of working in a close-knit team in an area that wasn’t finance (where Mum, a caustic and forbidding figure, puritanical in matters of sex and money, spent her career). Philosophical Meditation can, among other things, save us a lot of time.