Work • Business Skills

The Acceptance of Change

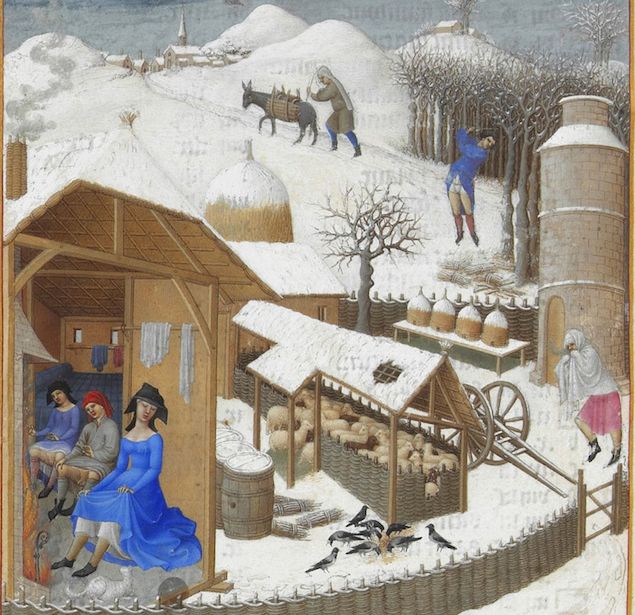

For most of human history, people did not believe that the world changed very much or, for that matter, that change could ever be positive. Stability and cyclicality were the ideals. The same stories were told again and again, time was understood to turn like a wheel rather than move like an arrow, technology hardly advanced, trades were handed down from generation to generation and the social order appeared immutable.

We, by contrast, are obsessed with, and laud, change. We are taught to regard widespread and frequent change as inescapable – and a profound advantage. We feel only pity for yesteryear and measure our virtue by our openness to continuous revolution. To confess to a fear of change is to risk being labelled as that most damned of contemporary figures: a reactionary.

Yet our adaptability to change is neither a given, nor always entirely straightforward. The arena in which the advantages of change are at their most evident is science. The prototype helicopter built by Paul Cornu in 1907 was a hugely gallant contraption of plywood, string and bicycle wheels. But it is, without dispute, much less good at vertical takeoff and hovering than the latest machines from AgustaWestland. The direction of change in technology is clear and the sense of progress obvious. Medicine provides countless instances of the same kind – which seduces us into supposing that change in general must always bring extreme benefits, extending a hopefulness which is entirely justified in specific areas like rotor blades and antibiotics to other areas where its relevance and legitimacy are, in fact, much less secure.

For example, politics and society. We know – from folklore or our own lives – that the old ways were at points not merely anachronistic. They contained important truths and kinds of happiness that have now escaped our grasp. The villages were quieter, the shops more restricted, the manners more sober, but there was an openness to experience, a groundedness and a gratitude that we may long for in the frenzy of the kaleidoscopic present. In order to summon the will to action, to rouse ourselves and our communities from inertia, we have no choice but to tactically overestimate the advantages that accrue from change. We do this around marriage, divorce, moving country, starting a business or shifting the children’s schools. It’s not that there will never be a good result, simply that there will of course be a range of subtle losses too. Not all goods can coexist. The outcome is always more ambivalent than we can quite imagine. Nostalgia is not just for the simple-minded, it’s a natural response to what is lost even with every genuine improvement.

However open to change we might be, it’s in the nature of revolutions that we have a bad habit of missing them. Often, they simply come too fast. For many generations, people in the ancient city of Pompeii lived a prosperous life. The soil was good, the climate was kindly. They built gracious houses. They planted vineyards on the slopes of nearby Mount Vesuvius while all along, the pressure of the magna inside slowly built up. The people gave dinner parties, struggled for status, bought works of art and scanned the horizon for changes, positive and negative. Just no one considered the peak above the city skyline. The story of Pompeii is moving because it is a story of an innocence, in which we know ourselves to be at some level implicated. For us too, something we are blithely ignoring will be the probable cause of our sudden downfall. We are steering blind, pursuing our ordinary business on the natural assumption that whatever feels secure today will be so tomorrow. We too have no real idea where the next explosion may come from.

Or else we fail to adapt because change is so slow. The sea may be a better metaphor than a volcano. Year on year, the waves gradually eat into the rocks; complete change occurs through minute imperceptible actions. We can’t believe that small lapping motions could win against a huge edifice of rock – but they can.

Good theorists of change do not ultimately focus so much on the tempo of change, they identify fundamental features of human nature and wonder how changes will relate to them. When Thomas Edison showed off the first light bulb, it hardly looked like the world was about to be transformed. It was a bizarre-looking contraption, utterly unlike anything people would want in their homes. Gas was (at first) so much safer and cheaper. Potential backers were deeply sceptical. But when the great banker J. P. Morgan saw it, he grasped its possibilities at once. The bulb looked ridiculous, but only in superficial ways. Morgan saw past what was odd and off-putting and recognised an eternal idea in a strange guise. The banker was good at what we would call pattern recognition. He had the confidence and wisdom to see continuity when others thought only in terms of ugly rupture. He had seen change before, with railroads and steel, and had understood these as new approaches to age-old problems. Morgan had – as it were – studied other exploding mountains.

We underestimate opportunities for change in part because our lives are so short. We can generally directly witness only a few revolutions in them. So we are fooled by impressions of stability – like children who consider their childhood home as an eternal part of the earth. Our congenital error is to imagine that what appears solid must be so. We get used to gas lamps, they have been around since we arrived on the planet, so why would they vanish? We get used to our tidy orchards maturing in the sun on the slopes of a fertile mountain; why would an inferno come here? The error has long fascinated philosophers. Bertrand Russell imagined a turkey used to being fed by a farmer. Turkeys have, like us, short memories so when it hears the tread of the farmer’s boots, it feels sure that – of course – it is about to be fed, as always. Then it’s the week before Christmas. The turkey is a creature of habit, as are we for much of the time, but we do in theory at least, have reason and therefore a key advantage. A philosophical turkey would have wondered why the farmer was helping him every day and would have speculated on possible reasons so far unknown. The presence of a mysterious factor would have haunted the imagination of the benighted animal. The response to complacency is not so much to be continually on edge as to attempt to think more deeply and more sceptically about the workings of reality.

We are undermined, too, by a false sense of hierarchy about what qualifies as trivial and what is important. We carry around with us implicit and distorted ideas as to what it must be worth paying attention to – and what we can safely ignore. The early Norwegian settlers in Greenland suffered terrible hardships, and eventually died out, because they refused to adopt the survival skills and strategies known to the Inuit inhabitants. The Norwegians could not believe that such strange looking – and apparently unsophisticated – people could teach them anything. To their fatal cost they refused to learn, because the lessons being offered came in wrappings that violated all their expectations of what sophisticated intelligence could look like. Similarly, the elite of the United Kingdom went into grave economic decline in the mid-twentieth century in large part because its insular characters were resistant to learning about the nature of major economic change from people they deemed their radical inferiors: American business people. We turn down the Beatles, or dismiss Socrates or Van Gogh as fools because we are readier to follow a familiar script of what is valuable rather than assess the true merits of what is before us on every occasion. We forget what odd guises the truly great ideas have always tended to adopt.

It is in the end very understandable that change should be so frightening or at least sad: we will not be around for most of it. Lingering beneath our occasional lack of adaptability is a dread of the change that will one day wipe us away. It is because we are so exposed to change in ourselves that we seek to make or protect things that will outlast us, businesses included. We have so much to cope with in terms of change in our bodies, no wonder if we often find ourselves deeply interested in things that resist change in the world outside. We define some of the things we most care about when we dare to ask ourselves what we hope will never change.