Leisure • Political Theory

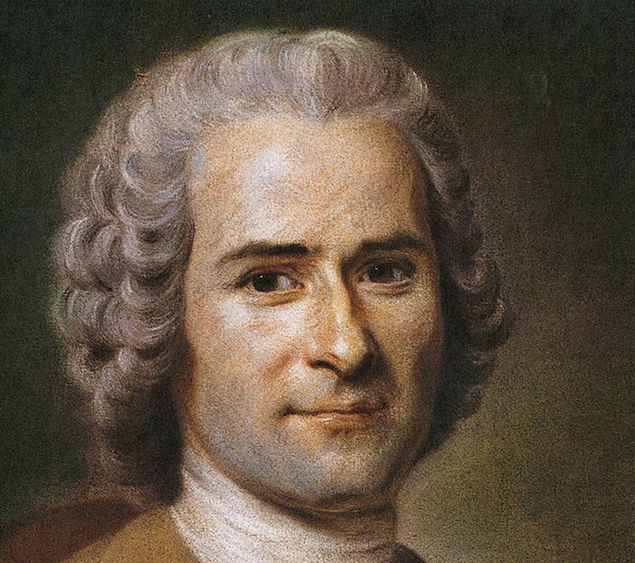

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Modern life is, in many ways, founded around the idea of progress: the notion that as we know more (especially about science and technology), and as economies grow larger, we’re bound to end up happier. Particularly in the eighteenth century, as European societies and their economies became increasingly complex, the conventional view was that mankind was firmly set on a positive trajectory; moving away from savagery and ignorance toward prosperity and civility. But there was at least one eighteenth-century philosopher who was prepared to vigorously question the “Idea of Progress” – and who continues to have very provocative things to say to our own era.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the son of Isaac Rousseau, an educated watchmaker, was born in Geneva in 1712. Almost immediately, Rousseau suffered the first of what he would later call his “misfortunes” – just nine days after giving birth, his mother, Suzanne Bernard, died from complications which arose from a traumatic and complicated labour. When Rousseau was ten, his father got into a legal dispute and the family was forced to flee to the city of Bern where Isaac would later marry for a second time. From that point on, Rousseau’s life was marked by instability and isolation. Throughout his teenage years and adulthood, he changed homes frequently; sometimes in search of love and acclaim; sometimes just to escape persecution.

As a young man, Rousseau went to Paris and there was exposed to the opulence and luxury that was the order of the day in ancien regime Paris; the aspirational bourgeoisie did their best to emulate the tastes and styles exhibited by both royalty and aristocracy, only adding to the competitive spirit that fuelled the burgeoning Parisian social scene. The Paris Rousseau was exposed to was a far cry from his birthplace of Geneva, a city that was sober and deeply opposed to luxury goods.

A theatre in Paris during Rousseau’s time.

Rousseau’s life was shaped by some key chance turning points. One of the most significant of these occurred in 1749 as he read a copy of a newspaper, the Mercure de France, that contained an advert for an essay on the subject of whether recent advances in the arts and sciences had contributed to the “purification of morals”. Upon reading the note placed there by the Académie de Dijon, Rousseau experienced something of an epiphany. It struck him, seemingly for the first time, that civilisation and progress had not in fact improved people; they had exacted a terrible destructive influence on the morals of human beings who had once been good.

Rousseau took this insight and turned it into the central thesis of what became his celebrated Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, which won the first prize in the newspaper competition. In the essay, Rousseau offered a scathing critique of modern society that challenged the central precepts of Enlightenment thought. His argument was simple: individuals had once been good and happy, but as man had emerged from his pre-social state, he had become plagued by vice and reduced to pauperism.

Rousseau went on to sketch a history of the world not as a story of progress from barbarism to the great workshops and cities of Europe, but of regress away from a privileged state in which we lived simply, but had the chance to listen to our needs. In technologically backward prehistory, in Rousseau’s “state of nature” (l’état de nature), when men and women lived in forests and had never entered a shop or read a newspaper, the philosopher pictured people more easily understanding their own minds, and so being drawn towards essential features of a satisfied life: a love of family, a respect for nature, an awe at the beauty of the universe, a curiosity about others, and a taste for music and simple entertainments. The state of nature was also moral, guided by pitié, (pity) for others and their suffering. It was from this state that modern commercial ‘civilisation’ had pulled us, leaving us to envy and long for and suffer in a world of plenty.

Rousseau was aware of just how controversial his conclusion was – he anticipated “a universal outcry” against his thesis and the Discourse indeed prompted a considerable number of responses. Rousseau had found fame.

What was it about civilisation that he thought had corrupted man and produced this moral degeneracy? Well, at the root of his hostility was his claim that the march toward civilisation had awakened in man a form of “self-love” – amour-propre – that was artificial and centred on pride, jealousy, and vanity. He argued that this destructive form of self-love had emerged as a consequence of people moving to bigger settlements and cities where they had begun to look to others in order to glean their very sense of self. Civilised people stopped thinking about what they want and felt – and merely imitated others, entering into ruinous competitions for status and money.

Discourse on the Origins of Inequality

Primitive man, noted Rousseau, did not compare himself to others but instead focused solely on himself – his objective was simply to survive. Though Rousseau didn’t actually employ the term ‘noble savage’ in his philosophical writings, his account of natural man unleashed a fascination with this concept. For those who might see this as an impossibly romantic story to be explained away as the fancy of an excitable author with a grudge against modernity, it is worth reflecting that if the eighteenth century listened to Rousseau’s argument, it was primarily because it had before it one stark example of its apparent truths in the shape of the fate of the native Indian populations of North America.

Reports of Indian society drawn up in the sixteenth century described it as materially simple, but psychologically rewarding: communities were small, close-knit, egalitarian, religious, playful and martial. The Indians were undoubtedly backwards in a financial sense. They lived off fruits and wild animals, they slept in tents, they had few possessions. Every year, they wore the same pelts and shoes. Even a chief might own no more than a spear and a few pots. But there was a distinct level of contentment amidst the simplicity.

An early depiction of life in a Native American village.

However, within only a few decades of the arrival of the first Europeans, the status system of Indian society had been revolutionised through contact with the technology and luxury of European industry. What mattered was no longer one’s wisdom or understanding of the ways of nature, but one’s ownership of weapons, jewellery and alcohol. Indians now longed for silver earrings, copper and brass bracelets, tin finger rings, necklaces made of Venetian glass, ice chisels, guns, alcohol, kettles, beads, hoes and mirrors.

These new enthusiasms did not come about by coincidence. European traders deliberately attempted to foster desires in the Indians, so as to motivate them to hunt the animals pelts the European market was demanding. Sadly, their new wealth didn’t appear to make the Indians much happier. Certainly the Indians worked harder. Between 1739 and 1759, the two thousand warriors of the Cherokee tribe were estimated to have killed one and a quarter million deer to satisfy European demand. But rates of suicide and alcoholism rose, communities fractured, factions squabbled. The tribal chiefs didn’t need Rousseau to understand what had happened, but they concurred totally with his analysis nevertheless.

Contemporary portrait of Rousseau.

Rousseau died in 1778, aged 66, while taking a walk outside Paris. He’d spent the last years a celebrity, living with his common-law wife. But he also was constantly on the move fleeing persecution in Geneva after some of his more radical ideas, especially about religion, caused controversy (the stress of this had also caused a series of mental breakdowns). He is now buried in the Pantheon in Paris, and the Genevans celebrate him as their most famous native son.

In an age such as our own, one in which opulence and luxury can be deemed both desirable and exceedingly offensive, Rousseau’s musings continue to reverberate. He encourages us to sidestep jealousy and competition and instead look solely to ourselves in identifying our self worth. It is only by resisting the evil of comparison, Rousseau would tell us, that we can avoid feelings of misery and inadequacy. Though difficult, Rousseau was confident that this was not impossible, and he thus leaves behind a philosophy of fundamental criticism, but also one of profound optimism. There is a way out of the misery and corruption produced by the mores and institutions and modern civilisation – the hard part is that it involves looking to ourselves and reviving our natural goodness.