Leisure • Sociology

Max Weber

Max Weber is one of the four philosophers best able to explain to us the peculiar economic system we live within called Capitalism (Emile Durkheim, Karl Marx and Adam Smith are the others).

Born in Erfurt in Germany in 1864, Weber grew up to see his country convulsed by the dramatic changes ushered in by the Industrial Revolution. Cities were exploding in size, vast companies were forming, a new managerial elite was replacing the old aristocracy. Weber’s father, successful in business and politics, prospered greatly from this new era, leaving his son with a fortune that would allow him the independence to be a writer. His mother was a sober, withdrawn figure, who mostly stayed at home practising an extremely pious and sexually-strict version of Christianity.

Weber became a successful academic at a young age. But when he was in his mid-thirties, during a family get-together, he fell into a grave quarrel with his father over the latter’s treatment of his mother. Weber senior died the next day and the son believed he might inadvertently have killed him. This catapulted him into severe depression and anxiety. Weber had to give up his university job and lay more or less mute on a sofa for two years.

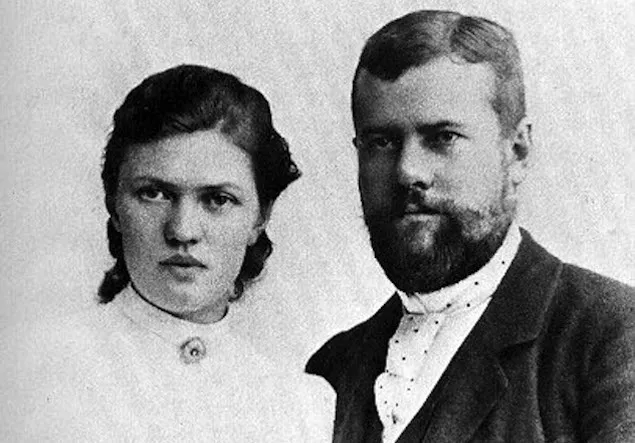

Max and Marianne Weber in 1894

His wife, Marianne, turned out to be unhelpfully similar to his mother. The marriage was unconsummated and filled with neurotic complaints on both sides. Weber’s path to intellectual recovery began after he had a liberating affair with a sexually-progressive 19-year-old student, Else von Richthofen (whose sister, Frida, comparable in temperament, was married to the novelist D. H. Lawrence). Max Weber had the sort of life that his contemporary, Freud, was born to address.

Weber was largely unknown during his lifetime. But his fame has grown exponentially ever since – because he originated some key ideas with which to understand the workings and future of Capitalism.

1. Why does Capitalism exist?

Capitalism might feel normal or inevitable to us but, of course, it isn’t. It came into existence only relatively recently, in historical terms, and has successfully taken root in just a limited number of countries.

The standard view is that Capitalism is the result of developments in technology (particularly, the invention of steam power).

But Weber proposed that what made Capitalism possible was a set of ideas, not scientific discoveries – and in particular religious ideas.

Religion made Capitalism happen. Not just any religion; a very particular, non-Catholic kind of the sort that flourished in Northern Europe where Capitalism was – and continues to be – particularly vigorous. Capitalism was created by Protestantism, specifically Calvinism, as developed by John Calvin in Geneva and by his followers in England, the Puritans.

In his great work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, published in 1905, Weber laid out some of the reasons why he believed Protestant Christianity had been so crucial to Capitalism:

i) Protestantism makes you feel guilty all the time:

Catholics have it – relatively – easy in Weber’s analysis. Believers who have strayed are able to confess their transgressions at regular intervals and can be ‘cleansed’ by priests and thereby recover a sense of their good name in the eyes of God. But no such purifications are available to Protestants, for only God is thought able to forgive and He won’t make his intentions known until the Day of Judgement. Until then, Weber alleged, Protestants are left with heightened feelings of anxiety as well as life-long guilty desires to prove their virtue before a severe, all-seeing but silent God.

ii) God likes hard work

In Weber’s eyes, Protestant guilt feelings were diverted into an obsession with hard work. The sins of Adam could only be expunged through constant toil. To rest, relax and go hunting – as the old Catholic aristocracy liked to do – was to ask for divine trouble. Not coincidentally, there were far fewer festivals and days of rest in Protestantism. God didn’t like time off. Money earnt wasn’t to be blown in feasts celebrating the here-and-now. It was always and only to be reinvested for tomorrow.

iii) All work is holy

Catholics had limited their conception of holy work to the activities of the clergy. But now Protestants declared that work of any kind could and should be done in the name of God, even jobs like being a baker or an accountant. This lent new moral energy and earnestness to all branches of professional life. Work was no longer just about earning a living, it was to be part of a religious vocation connected with proving one’s virtue to God. The clerk was meant to approach his work at the office with all the seriousness and piety of a monk.

iv) It’s the community, not the family, that counts

In Catholic countries, the family was (and often still is) everything. One would regularly give jobs to relatives, help out indolent uncles and lightly swindle the central authorities for family gain without too much compunction. But Protestants took a less benevolent view of family. The family could be a haven for selfish and egoistic motives, running counter to Jesus’s injunctions that a Christian should be concerned with the family of all believers, not his or her specific family. For early Protestants, one was meant to direct one’s selfless energies to the community as a whole, the public realm where everyone deserved fairness and dignity. To stick up for one’s family over and against the claims of the wider group was nothing less than a sin; it was time to do away with narrow vested interests and clan loyalties.

v) There aren’t miracles

Protestantism turned its back on miracles. God wasn’t thought to be lever-pulling behind the scenes day-to-day. One couldn’t get prayers directly answered. Heavenly power didn’t intervene in a fantastical, childish way. Weber called this ‘the disenchantment of the world.’ Instead, in the Protestant philosophy, the emphasis fell on human action: the day to day world was ruled by facts, by reason and by the discoverable laws of science. And therefore, prosperity was not mysteriously ordained by God and couldn’t be won through imploring prayers. It could only be the result of thinking methodically, acting honestly and working industriously and sensibly over many years.

Taken together, these five factors created, in Weber’s eyes, the crucial catalytic ingredients for Capitalism to take hold. In this analysis, Weber was in direct disagreement with Karl Marx, for Marx had proposed a materialist view of Capitalism (where technology was said to have created a new capitalist social system), whereas Weber now advanced an idealist one (suggesting that it was in fact a set of ideas that had created Capitalism and given the impetus for its newfound technological and financial arrangements).

Karl Marx in 1875

The argument between Weber and Marx pivoted around the role of religion. Marx had argued that religion was ‘the opium of the masses’, a drug that induced passive acceptance of the horrors of Capitalism. But Weber turned this dictum on its head. It was religion that was in fact the cause and foremost supporter of Capitalism. People didn’t tolerate Capitalism because of religion, they only became capitalists as a result of their religion.

2. How do you develop Capitalism around the world?

There are about 35 countries where Capitalism is now well developed. It probably works best in Germany, where Weber first observed it. But in the remaining 161 nations, it arguably isn’t working well at all.

This is a source of much puzzlement and distress. Billions of dollars in aid are transferred every year from the rich to the poor world, and are spent on malaria pills, solar panels and grants for irrigation projects and women’s education.

But a Weberian analysis tells us that these materialist interventions will never work, because the problem isn’t really a material one to begin with. One has to start at the level of ideas.

What the World Bank and the IMF should be giving sub-Saharan Africa is not money and technology but ideas.

In the Weberian analysis, certain countries fail to succeed at Capitalism because they don’t feel anxious and guilty enough, they trust too much in miracles, they like to celebrate now rather than reinvest for tomorrow and their members feel it’s acceptable to steal from the community in order to enrich their families, favouring the clan over the nation.

Weber didn’t believe that the only way to be a successful Capitalist country was actually to convert to Protestantism. He argued that Protestantism had merely brought to their first fruition ideas which could now subsist outside of religious ideology.

Today Weber would counsel those who wish to spread Capitalism to concentrate on our equivalent of religion: culture. It is a nation’s attitudes, hopes and sense of what life is about that produces an economy that either flourishes or flounders. The path to reforming an economy shouldn’t hence wind through material aid, it should go through cultural assistance. The decisive question for an economy is not what the rate of inflation is, but what is on TV tonight.

3. Why is Capitalism not going so well in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (the poorest country on earth)?

Because, Weber would tell us, this unfortunate nation has the wrong mentality, one far removed from that of Rhineland Germany. They believe in clans, they have magical thinking, they don’t believe that God would Himself command them to be an honest mechanic or hairdresser…

Weber’s point is that if Capitalism is going to take root in developing nations – and bring the advantages of higher productivity and greater wealth – then we will need to look to changing mentalities, instilling something akin to an updated version of the attitudes of Calvinism.

Weber’s views on global development emerged in two books he wrote on two religions that he felt were extremely unhelpful to Capitalism, The Religion of India and The Religion of China. For Weber, the caste system of the Hindus assigns everyone to a status they can’t escape and therefore makes any sustained commercial effort futile. The belief in samsara – the transmigration of souls – also inspires the view that nothing substantial can change until the next life. At the same time, a Hindu ideology of the clan takes pressure off individual responsibility and encourages nepotism rather than meritocracy. These ideas have economic consequences; they are why nowadays, Weberians would argue, there are many excellent public hospitals in Geneva and Erfurt and not too many in Chennai or Varanasi.

Weber noted similarly unhelpful factors in China. There Confucianism gives too much weight to tradition. No one feels able to rethink how things are done. The devotion to bureaucracy encourages a static society – whereas entrepreneurship arises from a fruitful mixture of anxiety and hope.

4. How can we change the world?

Weber was writing in an age of revolution. Lots of people around him were trying to change things: communists, socialists, anarchists, nationalists, separatists.

He too wanted things to change, but he believed that one first had to work out how political power operated in the world.

Anton von Werner, The Proclamation of Prussian king Wilhelm I, 1877

He believed that humanity had gone through three distinct types of power across its history. The oldest societies operated according to what he called ‘traditional authority.’ This was where kings relied on appeals to folklore and divinity to justify their hold on power. Such societies were deeply inert and only rarely allowed for initiative

These societies had subsequently been replaced by an age of ‘charismatic authority’, where a heroic individual, most famously a Napoleon, could rise to power on the back of a magnetic personality – and change everything around him through passion and will.

But, Weber insisted, we were now long past this period of history, having entered a third age of ‘bureaucratic authority.’ This is where power is held by vast labyrinthine bureaucracies whose workings are entirely baffling to the average citizen. It’s not obvious what all the functionaries actually do in meetings and at their desks. Bureaucracy achieves its power via knowledge: only the bureaucrats know how stuff works, and it will take an outsider years to work it out (for example, how housing policy or the educational curriculum are actually structured). Most simply give up – usefully for the powers that be…

The dominance of bureaucracy has major implications for anyone trying to change a nation. There is often an understandable, but misguided, desire to think one just has to change the leader, who is imagined as a kind of super-parent personally determining how everything goes. But in fact, removing the leader almost never has the degree of impact that is hoped for. (The replacement of Bush by Obama did not lead, for example, to all the changes some people expected; Weber would not have been surprised).

Weber knew that today one can’t bring about significant social change just by charisma. It can feel as if political change should be driven by fiery rhetoric, marches, fury and grand, exciting gestures, like publishing a bestselling revolutionary book. But Weber is pessimistic about all such hopes, for they are misaligned with the reality of how the modern world works. The only way to overcome the power lodged within bureaucracy is through knowledge and systematic organisation.

Weber encourages us to see that change is not so much impossible as complicated and slow. If we are to get things to go better, much of it will have to come through outwardly very undramatic processes. It will be through the careful marshalling of statistical evidence, patient briefings to ministers, testimonies to committee hearings and minute studies of budgets.

Conclusion

Weber, though personally a cautious man, is an unexpected source of ideas on how to change things. He tells us how power works now and reminds us that ideas may be far more important than tools or money in changing nations. It is a hugely significant thesis. We learn that so much which we associate with vast impersonal external forces (and which hence feels entirely beyond our control) is, in fact, dependent upon something utterly intimate and perhaps more malleable: the thoughts in our own heads.