Leisure • Western Philosophy

Michel de Montaigne

We generally think that philosophers should be proud of their big brains, and be fans of thinking, self-reflection and rational analysis.

But there’s one philosopher, born in France in 1533, with a refreshingly different take. Michel de Montaigne was an intellectual who spent his writing life knocking the arrogance of intellectuals. In his great masterpiece, the Essays, he comes across as relentlessly wise and intelligent – but also as constantly modest and keen to debunk the pretensions of learning. Not least, he is extremely funny…: ‘to learn that we have said or done a stupid thing is nothing, we must learn a more ample and important lesson: that we are but blockheads… On the highest throne in the world, we are seated, still, upon our arses.’ And, lest we forget: ‘Kings and philosophers shit, and so do ladies.’

Montaigne was a child of the Renaissance and the ancient philosophers popular in Montaigne’s day had believed that our powers of reason could afford us a happiness and greatness denied to other creatures. Reason allowed us to control our passions and temper the wild demands of our bodies, wrote philosophers like Cicero. Reason was a sophisticated, almost divine, tool offering us mastery over the world and ourselves. But this characterisation of human reason enraged Montaigne. After hanging out with academics and philosophers, he wrote, “In practice, thousands of little women in their villages have lived more gentle, more equable and more constant lives than [Cicero].”

His point wasn’t that human beings can’t reason at all, simply that they tend to be far too arrogant about their brains. “Our life consists partly in madness, partly in wisdom,” he wrote. “Whoever writes about it merely respectfully and by rule leaves more than half of it behind.”

Perhaps the most obvious example of our madness is the struggle of living with a human body. Our bodies smell, ache, sag, pulse, throb and age. Montaigne was the world’s first and possibly only philosopher to talk at length about impotence, which seemed to him a prime example of how crazy and fragile our minds are.

Montaigne had a friend who had grown impotent with a woman he particularly liked. Montaigne did not blame his penis: “Except for genuine impotence, never again are you incapable if you are capable of doing it once.” The problem was the mind, the oppressive notion that we had complete control over our bodies, and the horror of departing from this portrait of normality that had left the man unable to perform. The solution was to redraw the portrait; it was by accepting a loss of command over the penis as a harmless possibility in love-making that one could pre-empt its occurrence – as the stricken man eventually discovered. In bed with a woman, he learnt to,

“Admit beforehand that he was subject to this infirmity and spoke openly about it, so relieving the tensions within his soul. By bearing the malady as something to be expected, his sense of constriction grew less and weighed less heavily on him.”

Montaigne’s frankness allowed the tensions in the reader’s own soul to be relieved. A man who failed with his girlfriend and was unable to do any more than mumble an apology, could regain his forces and soothe the anxieties of his beloved by accepting that his impotence belonged to a broad realm of sexual mishaps, neither very rare nor very peculiar. Montaigne knew a nobleman who, after failing to maintain an erection with a woman, fled home, cut off his penis and sent it to the lady “to atone for his offence.” Montaigne proposed instead that:

“If [couples] are not ready, they should not try to rush things. Rather than fall into perpetual wretchedness by being struck with despair at a first rejection, it is better… to wait for an opportune moment… a man who suffers a rejection should make gentle assays and overtures with various little sallies; he should not stubbornly persist in proving himself inadequate once and for all. ”

Throughout his work, Montaigne took farts, penises, and shitting as serious topics for contemplation. He told his readers, for example, that he liked quiet when sitting on the toilet: “Of all the natural operations, that is the one during which I least willingly tolerate being disrupted.”

Ancient philosophers had recommended that one try to model oneself on the lives of certain esteemed people, normally philosophers. In the Christian tradition, one should model one’s life on that of Christ. The idea of modelling is attractive; it suggests we need to find someone to guide and illuminate our path. But it matters a lot what kind of portraits are around. What we see evidence for in others, we will attend to within, what others are silent about, we may stay blind to or experience only in shame. Montaigne is refreshing because he provides us with a life which is recognisably like our own and yet inspiring still – a very human ideal.

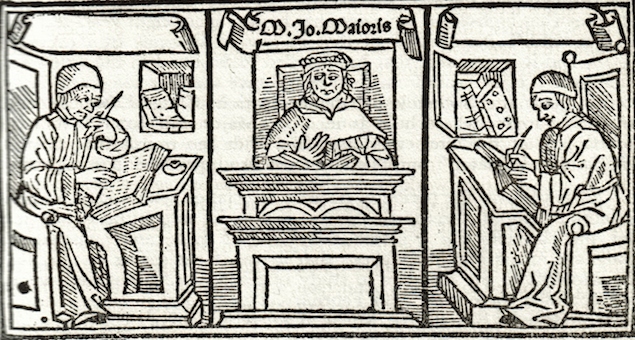

Academia was deeply prestigious in Montaigne’s day, as in our own. Montaigne was an excellent scholar but he hated pedantry. He only wanted to learn things that were useful and relentlessly attacked academia for being out of touch: “If man were wise, he would gauge the true worth of anything by its usefulness and appropriateness to his life,” he said. Only that which makes us feel better may be worth understanding.

Montaigne noted snobbery and pretension in many areas – and constantly tried to bring us back to earth.

“Storming a breach, conducting an embassy, ruling a nation are glittering deeds. Rebuking, laughing, buying, selling, loving, hating and living together gently and justly with your household – and with yourself – not getting slack nor being false to yourself, is something more remarkable, more rare and more difficult. Whatever people may say, such secluded lives sustain in that way duties which are at least as hard and as tense as those of other lives.”

In this vein, Montaigne mocked books that were difficult to read. He admitted to his readers that he found Plato more than a little boring – and that he just wanted to have fun with books:

“I am not prepared to bash my brains for anything, not even for learning’s sake however precious it may be. From books all I seek is to give myself pleasure by an honourable pastime… If I come across difficult passages in my reading I never bite my nails over them: after making a charge or two I let them be… If one book wearies me I take up another.”

He could be pretty caustic about incomprehensible philosophers:

“Difficulty is a coin which the learned conjure with so as not to reveal the vanity of their studies and which human stupidity is keen to accept in payment.”

Montaigne observed how an intimidating scholarly culture had made all of us study other people’s books before we study our own minds. And yet, as he put it: “We are richer than we think, each one of us.”

We may all arrive at wise ideas if we cease to think of ourselves as so unsuited to the task because we aren’t two thousand years old, aren’t interested in the topics of Plato’s dialogues and have a so-called ordinary life.

“You can attach the whole of moral philosophy to a commonplace private life just as well as to one of richer stuff.”

It was perhaps to bring the point home that Montaigne offered so much information on exactly how ordinary his own life was – why he wanted to tell us,

That he didn’t like apples

“I am not overfond …of any fruit except melons.”

That he had a complex relationship with radishes

“I first of all found that radishes agreed with me; then they did not; now they do again.”

That he practised the most advanced dental hygiene

“My teeth…have always been exceedingly good… Since boyhood I learned to rub them on my napkin, both on waking up and before and after meals.”

That he ate too fast

“In my haste I often bite my tongue and occasionally my fingers.”

And liked wiping his mouth

“I could dine easily enough without a tablecloth, but I feel very uncomfortable dining without a clean napkin… I regret that we have not continued along the lines of the fashion started by our kings, changing napkins likes plates with each course.”

Trivia perhaps, but symbolic reminders that there was a thinking “I” behind this book, that a moral philosophy had issued – and so could issue again – from an ordinary, fruit-eating soul.

There is no need to be discouraged if, from the outside, we look nothing like those who have ruminated in the past.

In Montaigne’s redrawn portrait of the adequate, semi-rational human being, it is possible to speak no Greek, fart, change one’s mind after a meal, get bored with book, be impotent and know none of the Ancient philosophers.

A virtuous, ordinary life, striving for wisdom but never far from folly, is achievement enough.

Montaigne remains the great, readable intellectual with whom we can laugh at intellectuals and pretensions of many kinds. He was a breath of fresh air in the cloistered, unworldly, snobbish corridors of the academia of the 16th century – and because academia has, sadly, not changed very much, he continues to be an inspiration and a solace to all of us who feel routinely oppressed by the pedantry and arrogance of so-called clever people.