What Is the Point of Museums?

The prestige of museums has never been higher. Every city that wishes to be on the map knows it must build one. No foreign trip feels complete without taking up the guidebook’s recommendation to visit one. We regularly hear that museums are our ‘new cathedrals’, in other words, the most meaningful and prestigious spaces we have.

Nevertheless, there are – behind the scenes – some serious drawbacks to museums:

– the art in some of them is often – privately – seen as the least interesting bit about them.

– the needs that used to drive people to cathedrals aren’t really being taken care of in our museums (needs that include the desire for serenity, the longing for community, the wish to transcend the everyday).

– we feel conflicted about the role of shopping in museums: is it respectable, where does it fit in?

– what is the balance between preservation of the old and the habits and appetites of the present?

Museums seem so natural and inevitable, we may be reluctant to ask what they are for. An answer is elusive because they are in truth an uncomfortable and rather novel amalgamation of functions:

– a gigantic filing cabinet for the past

– a community centre

– a place for artistic ecstasy

– a shop

– somewhere solemn now God is Dead

– works of architecture in themselves

We generally hold museum culture in extremely high regard. But, equally, we tend not to look very closely at why this culture has such prestige. In fact, we are encouraged to think it is unsophisticated, even vulgar, to ask what culture is for. The present ‘guardians of culture’ are deeply devoted to the idea that art should exist ‘for art’s sake.’ This idea achieved dominance in the late nineteenth century and continues to determine the frame through which we (largely unknowingly) view culture. It dictates that culture should never be appropriated for practical or ideological ends. This is a pity.

The 19th century theory of art for art’s sake was meant to release culture from the clutches of three tainted forces – religion, politics and commerce – each of which was deemed to want something rather too urgent and practical from cultural creators. In flight from these forces, critics asserted that culture was to be kept free of any sort of clearly stated ‘goal’ or ‘end’. It should exist in its own sphere and not be asked to ‘do’ anything much in the world (as religions, political parties and certain pre-modern societies, especially those of Greece and Rome, had explicitly asked it to). On the back of this idea were born all kinds of notions that persist to this day: the veneration of ambiguity and paradox, the horror at being asked what something might be for… Sensible cultural homage is associated with acquiring technical knowledge, with taking advanced qualifications in the humanities, with knowing historical details and with respecting, at least in substantial part, the canon as it is now defined.

Strangely, what we are not generally encouraged to do – and indeed what we might be actively dissuaded from attempting – is to connect up works of culture with the agonies and aspirations of our own lives. It is quickly deemed vulgar, even repugnant, to seek personal solace, encouragement, enlightenment or hope from high culture. We are not, especially if we are serious, meant to view cultural encounters as opportunities for didactic instruction.

In Leaving the Atocha Station, a novel by Ben Lerner, an American PhD student, used to considering art as material for academic analyses and scholarly seminars, visits Madrid’s Prado museum. In one of the quieter rooms, he spots a fellow visitor who moves slowly and looks intently at a range of key works, including Roger van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross, Paolo de San Leocadio’s Christ the Saviour and Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

What might it be right to do in front of this?

Rogier Van der Weyden, Descent from the Cross (1435–8)

What astonishes the graduate student and eventually the guards of the museum is that in front of each of these masterpieces, the visitor doesn’t merely politely look at the caption or the guidebook; he doesn’t just note the fine brushstroke and the azure of the skies. He bursts into tears and cries openly at the sorrow and beauty on display, at the contrast between the difficulties of his own life and the spirit of dignity and nobility of the works on the wall. Such an outburst of intense emotion is deeply unusual in a museum (museums may routinely be referred to as our secular cathedrals, but they aren’t – as cathedrals once were – intended to be places to reveal one’s grief and gratitude). Listening to the man’s sobs, the guards at the Prado grow understandably confused and nervous. As the author puts it, they cannot decide:

whether he was the kind of man who would damage a painting, spit on it, tear it from the wall or scratch it with a key – or if he was having a profound experience of art… What is a museum guard to do…? On the one hand, you are a member of a security force charged with protecting priceless materials from the crazed… on the other hand…if your position has any prestige it derives precisely from the belief that [great art] could legitimately move a man to tears… Should the guards ask the man to step into the hall and attempt to ascertain his mental state… or should they risk letting this potential lunatic loose among the treasures of their culture?

The dilemma points with dry humour to the paradox of our contemporary engagement with culture: on the one hand, we insist on culture’s importance. On the other, we limit what we are meant to do with culture to a relatively polite, restrained and principally academic relationship, at points frowning on those who might treat it more viscerally and emotionally, as if it might be a sophisticated branch of a notorious category: self-help.

This resistance, however well-meaning, nevertheless misses that the great works of culture were almost invariably created to redeem, console and save the souls of their audiences. They were made, in one way or another, with the idea of changing lives. It is a particular quirk of modern aesthetics to sideline or ignore this powerful underlying ambition, to the point where to shed tears in front of a painting of the death of the son of God may put one at risk of ejection from a national museum.

In a better world, it would be recognised what a historical anomaly the idea of ‘art for art’s sake’ has been, running counter to centuries of historic mainstream thinking about the purpose of art. Almost all the art and culture that is to be found in museums, art galleries and libraries was produced by people who believed that art had a purpose which could be stated thus: it was meant to teach us how to be wise, self-aware, kind and reconciled to the darkest aspects of reality. The anti-utilitarian view is a rejection of more than 2,000 years of philosophising on the practical role of the arts.

The idea of art for art’s sake was originally motivated by a noble desire to honour culture, to say how special and important its fields were in a world sullied by meaner, utilitarian aims. Yet, inadvertently, this entrenched view has come to stand in the way of a full engagement with culture, suggesting that its disciplines should not in fact be consequential in the world; that they should not guide our beliefs or shape our habits; that they should not be appreciated for their wisdom or consoling power – for this would be to ‘use’ them…

A lot of the prestige which culture currently enjoys has been won at the expense of another field of human experience, the status of which has declined in direct relation to the rise in the status of art: religion. From the middle of the 19th century onwards, many people (Matthew Arnold, Nietzsche, Heidegger among them) came to the view that, as religion weakened its hold on society and upon people’s inner lives, it would be culture that could step in and perform many of the same roles as the faiths. Culture too could guide, exhort, reassure, console, inspire and censure. It was with this big ambition in mind that a period of vast investment in culture (in museums, in art galleries, in opera houses and libraries) proceeded. Culture would replace scripture. The great institutions of culture – the galleries and the universities – would be the new Cathedrals of Christendom.

In truth, art really can do for us a remarkable number of the very things that religion once did. Culture truly is in a position to replace many of the functions of scripture. Art too has the power to console us, it too can bring meaning and purpose, it too can increase our powers of empathy and generate a sense of community.

But in practice, we tend to pay only lip-service to these ideas. You used to go to the cathedral for some clear reasons: because you wanted to save your soul, because you were looking for comfort, you needed community, you wanted to develop your moral character or you were hoping for consolation and redemption. But if you turned up at a gallery or a university arts faculty with similarly intense, focused concerns, you would be considered very strange, regarded with suspicion and perhaps even declared insane.

However, in a wise and mature society, the therapeutic resources of culture would be taken very seriously. The visual arts, architecture, the humanities, galleries and museums would be deployed to help us cope with our troubles and to flourish, both individually and collectively. Museums would be particularly focused on satisfying a powerful need which churches used to cater for so well: the need for community.

II.

Let’s consider the issue of gift shops. Let’s imagine you’ve been around an art exhibition of a favourite artist. Perhaps it was Barbara Hepworth, the mid-20th-century British sculptor, accorded a show by the Tate Gallery in London. On display were some of her greatest works, including ‘Two Figures’ and ‘Pelagos.’

The show has made you intensely receptive to what one might call the vision of life promoted by Hepworth. It’s a confused feeling, but now that the show is over (you were there for forty minutes) you’d like to take that spirit back out into the world, you’d like to Hepworth-ify important parts of your daily existence. Hepworth seems to you an exemplar of a dignified British modernism that celebrates intellectual rigour, restrained sensuality, elegance, simplicity and harnessed emotional intensity. You want your surroundings and the tenor of your days to take on some of Hepworth’s ideology: you would love your workplace, your railway station, your TV programmes and your relationships to be influenced by her atmosphere (and strangely, it feels normal that the spirit of an artist might spread way beyond particular artworks and be applicable to fields as diverse as architecture and relationships).

It’s in this mood and with these covert aspirations that you find your way to the gift shop. It’s an extremely busy place. Almost everyone who goes to the show spends a few minutes looking around and the line at the till snakes out to the door. You’re excited and ready to spend. This – surely – is the opportunity to Hepworthify your life. So you look around the aisles: there are scholarly monographs (tracing Hepworth’s relationship with the St Ives School and with Henry Moore’s early etchings), there is a large catalogue, there are some postcards, there is a tea towel and there are pencils and mugs with Hepworth’s name on it. The latter seem the most popular items of all.

You want to be receptive to what is on offer but the gift shop seems not to welcome your aspirations. If only there had been other things for sale… Perhaps reproductions of the actual works or guides on how to Hepworth-ify your life… Your desires are rather unclear. All you know is that the gift shop has not lived up to expectations.

This is an important and no way isolated dilemma. The gift shop is quite simply the most important tool for the diffusion and understanding of art in the modern world. Though it appears to be a mere appendage to most museums, the gift shop is central to the project of art institutions. Its job is to ensure that the lessons of the museum – which concern beauty, meaning and the enlargement of the spirit – can endure in the visitor far beyond the actual tour of the premises and be put into use in daily life.

The means deployed, however, are rarely on target. Aside from books, gallery gift shops usually sell postcards and household items with the names of artists on them. Postcards are such important mechanisms because they improve our engagement with art. Officially, our culture sees them as tiny, pale shadows of the far superior originals in the galleries a few metres away. But the encounter we have with the postcard may well be deeper, more perceptive and more valuable to us, because the card allows us to bring our own reactions to it. It feels safe and acceptable to pin it on a wall, throw it away or scribble on the front of it and by being able to behave so casually around it, our responses come alive. We consult our own needs and interests; we take real ownership of the object and because it is permanently available, we keep looking at it at various times. We feel free to be ourselves around it – as so often, and sadly, we do not in the presence of the masterpiece itself.

That said, gift shops will rarely sell us actual reproductions of works; fake, copy, pastiche, forgery. Many of the most bitter insults of the art world are designed to denigrate anything which is not the actual product of the master’s hand. We’ve uncritically absorbed the idea that copies are worthless, deeply embarrassing kitsch. The nightmares of curators and gallery directors are haunted by copies. Hang a reproduction by mistake and your career is over. But why? Why are copies always supposed to be terrible? Even asking this straightforward question is suspect. Sometimes, of course, a copy truly violates the original. It mucks up all the details, it gets proportions weirdly wrong, the colours become garish. But not always. What if it’s a really good copy? What if the details are faithful? What if the shapes are harmonious and the colours lovely? A well-made reproduction can carry 99% of the meaning of the original. And maybe that’s all that really matters to us.

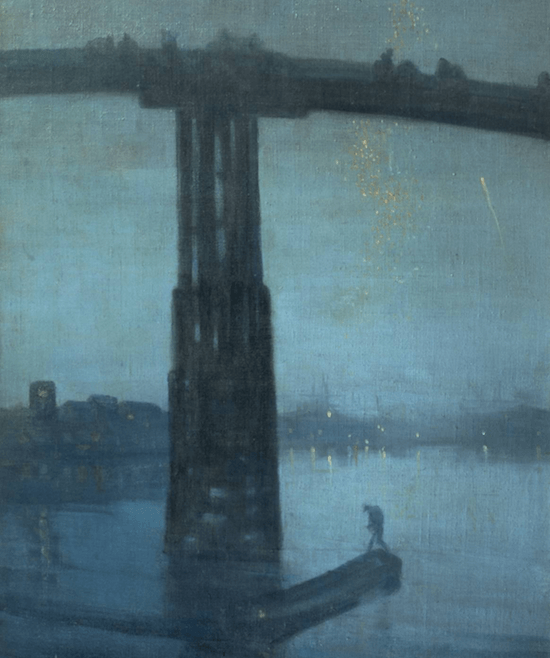

We’ve come to think that art belongs in art galleries and thereby condemned ourselves to encountering works at times dictated by museum opening hours and holiday schedules. We hardly ever get enraged in Tate Britain. So we’re unlikely ever to have direct need of Whistler’s immensely calming vista of fog, water and evening lights when we actually see it in the gallery. So it would be very much better if we could hang a copy of this work in the kitchen or by the bathroom door – places where angst has a tendency to congeal.

Art works have therapeutic power. But usually this passes us by. Not because we are insensitive or unworthy. But for a more basic reason. Their messages are hitting us at the wrong time – at moments when we’ve no need of them – like adverts for winter coats on the first day of spring. Copying is one much-needed solution to this problem, because copies allow us to locate these important, beneficial images in the places where we can encounter them in our times of need.

In the absence of copies, gift shops will sell us a lot of signed tea towels. They have discovered that people will buy objects heavily decorated with names of artists and their works: so we have Picasso table mats and Hepworth pencils.

Such objects try hard to pay homage to artists. They would like to beautify the world and carry the message of artists deep into our homes, so that the spirit of Hepworth would be alive when we prepared the morning tea and Picasso would be with us as we mopped away the orange juice from the kitchen counter. The ambition is noble, but its method of execution perhaps less so. The gift shop objects do have a faint link to the names they honour. Monet probably liked tea-towels; but it is unlikely that he would have wanted one with his own painting printed on it. The spirit of his best works of art, the things we love in them, may be much more consistent with (for instance) a completely plain and beautifully textured towel. This is more truly a Monet towel than one with his name on it.

The point isn’t to surround ourselves with objects which carry the actual identity of the artist and his or her work. It should be to get hold of objects which the artists would have liked, which are in keeping with the spirit of their works – and more broadly to look at the world through their eyes, and therefore to stay sensitive to what they saw in it.

One can imagine a different range of products to sell in the world’s gallery gift shops: objects which would be aligned with the values and ideals of artists rather than with their mere identities. The urge to buy something at the end of a museum visit is a serious one, because it involves an attempt to translate a sensibility we’ve come to know in one area (in carved wood or on canvases showing landscapes) and carry it over into another part of life (keeping the kitchen clean).

This points to the heart of what museums should really be about: giving us tools to extend the range and impact of what we admire in works of art across our whole lives. This is why the gift shop is, in fact, the most important place in the museum – if only its true potential could be grasped and made real.

III.

Let’s consider architecture: even very secular people tend to admit that when it comes to architecture, religions have done some very beautiful things. You can be left utterly cold by all the superstitious aspect of religions, and yet still be in awe at the profundity, intricacy and sheer prettiness of many mosques, temples, cathedrals and churches.

However, any nostalgia for these lovely buildings is always cut short by the thought that an end to faith must inevitably mean an end to the possibility of putting up anything like them today.

Yet on examination, it in no way logically follows that an end to our belief in sacred beings must mean an end to an attachment to certain sorts of atmosphere and architecture. In the absence of gods, we still retain a longing for calm, for community, for grandeur, for sweetness, for perspective – all of which can be found and celebrated through architecture.

We still need secular buildings that, like the temples and cathedrals of old, create feelings of awe, gratitude, wonder, mystery and silence; buildings that bring us together for special moments of the year (the passing of seasons) or to mark key moments of our lives (births, marriages, deaths). We need abstracted awe-inspiring sonorous spaces that take us out of the everyday and encourage contemplation, perspective, love and (at times) a pleasing terror.

There have over the last 200 years been a few examples of buildings that have learnt from religion without themselves being religious – buildings that can inspire new generations of patrons and architects.

The tradition of the non-religious ‘temple’ or ‘chapel’ begins with the French sociologist August Comte in the 19th century, who invented a secular religion, as he called it ‘A religion for humanity’ and designed some temples to go with it. He proposed that specially-built large halls would be decorated with portraits of the pantheon of his new religion’s secular saints, including Cicero, Pericles, Shakespeare and Goethe, all singled out by the founder for their capacity to inspire and reassure us.

A few of these Comte-inspired temples have been built. There is one in the Marais in Paris.

And three more in Brazil, including this one in Porto Alegre:

In the 20th century, the most notable secular chapel is perhaps Mark Rothko’s building in Houston, Texas, a place full of melancholy serenity:

Though nominally a Catholic building, the firm atheist Henri Matisse’s chapel in Vence in the South of France deserves to be counted among the great secular temples.

Equally impressive is Peter Zumthor’s field chapel near Cologne, Germany.

The most recent, and in many ways the most profound and thought-through addition to the genre has been a building by the artist Grayson Perry, dedicated to thwarted female creativity and potential – and ostensibly focused on the cult of a fictional (but so was Mary…) deity called Julie Cope.

The building has been designed to evoke a tradition of wayside and pilgrimage chapels in the landscape. It is a singular building, appearing as a small, beautifully crafted object amongst the trees and fields.

On a sunny weekend, the building – in north Essex, England – attracts hundreds of ‘pilgrims’:

They come to pay homage to the ‘deity’, Julie Cope, who holds out her hands in a gesture of comfort and sustenance:

These exceptional buildings are in fact only the beginning of a movement that could grow ever larger as the secular world becomes more conscious of its needs.

One could also, for example, imagine a building that would take up the traditional role of religious architecture in returning to us a sense of perspective.

– A Building for Perspective

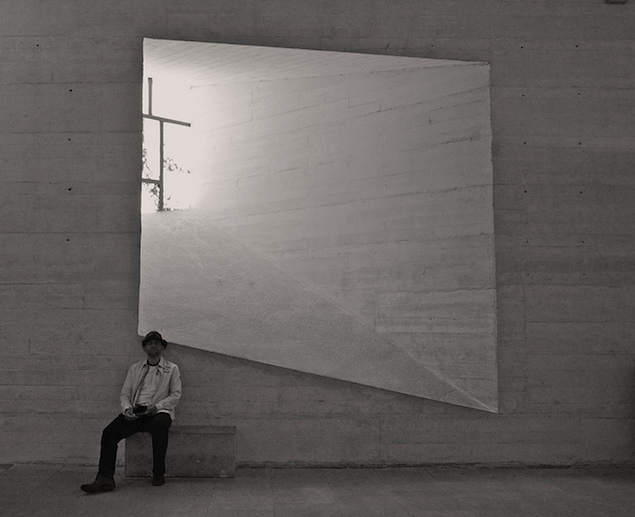

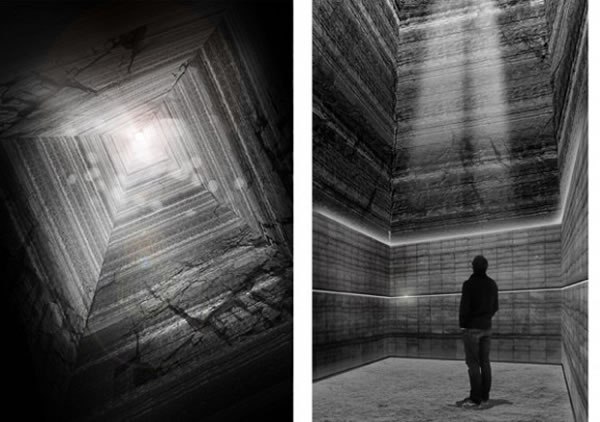

Considering how much of our lives we spend exaggerating our own importance, it would be highly useful to come across an architecture than answers our need for perspective. Architecture can perform a critical function by adjusting our impressions of our physical – and as a consequence also our psychological – size, by playing with dimensions, materials, sounds and sources of illumination. In certain buildings that are vast in scale or hewn out of massive, antique-looking stones; or in others that are dark save for a single shaft of light filtering in from a distant oculus; or silent but for the occasional sound of water dripping from a great height into a deep pool, we may feel that we are being introduced, with unusual and beguiling grace, to a not unpleasant sense of our own insignificance.

Imagine a ‘temple’ for perspective whose structure would represent the age of the earth, with each centimetre of height equating to one million years. Measuring 46 metres in all, the tower would feature, at its very base, a tiny band of gold only one millimetre thick, standing for mankind’s time on earth.

– A Retreat for Thinking

Or imagine a retreat for focusing our thoughts. It is one of the unexpected disasters of the modern age that our new unparalleled access to information has come at the price of our capacity to concentrate on anything much. The deep, immersive thinking which produced many of civilisation’s most important achievements is now under unprecedented assault. We are almost never far from some machine that will guarantee us a mesmerising and libidinous escape from reality. The feelings and thoughts which we have omitted to feel and think while looking at our screens are left to find their revenge in involuntary twitches and our ever-increasing inability to fall asleep when we should. So we can picture a building for thought would lend structure and legitimacy to moments of solitude. It would be a simple space, offering visitors little beyond a bench or two, a vista and a suggestion that they set to work on unravelling some of the troubling themes that they have been using their normal activity to suppress.

This is only a start: we also need new venues in which to get married, get to know other members of the community, mark deaths and ritualise and lend gravity to key moments of life.

Secular societies should revive and continue the underlying aims of religious architecture: to place us for a time in a thoughtfully-structured, three-dimensional space in order to educate and rebalance our inner selves.