Relationships • Finding Love

Why, Once You Understand Love, You Could Love Anyone

Irrespective of whether you consider Jesus a popular itinerant preacher or the Son of God, there’s a very odd thing about his views on love. He not only spoke a great deal about love: he went on to advocate that we love some highly surprising people.

At one point – described in chapter 7 of Luke’s Gospel – he goes to a dinner party and a local prostitute turns up – much to the disgust of the hosts. But Jesus is friendly and sweet and defends her against everyone else’s criticism. In a way that shocks the other guests, he insists that, at heart, she is a very good person.

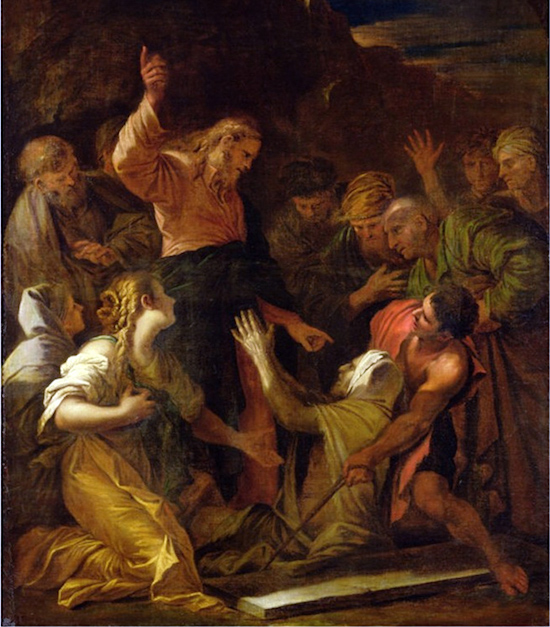

There’s another story (in Matthew, chapter 8) where Jesus is approached by a man with leprosy. He’s in a disgusting state. But Jesus isn’t shocked, reaches out his hand and touches the man. Despite the horrendous appearance, here is someone (in Jesus’s eyes) entirely deserving of closeness and kindness. In a similar vein, at other times, Jesus conspicuously argues that tax collectors, thieves and adulterers are never to be thought of as outside the circle of love.

Many centuries after his death, the foremost medieval thinker Thomas Aquinas defined what Jesus was getting at in this way of talking about love: the person who truly understands love could love anyone. In other words: true love isn’t specific in its target; it doesn’t fixate on particular qualities, it is open to all of humanity, even (and in a way especially) its less appealing examples.

Today, this can sound like a deeply strange notion of what love is, for our background ideas about love tend to be closely tied to a dramatic experience: that of falling in love, that is, finding one, very specific person immensely attractive, exciting and free of any failings or drawbacks. Love is, we feel, a response to an overt perfection of another person.

Yet – via some admittedly extreme examples – a very important aspect of love is being pushed to the fore in Jesus’ vision. And we don’t have to be Christian – that is, we don’t have to believe there’s an afterlife or that Jesus was born to a virgin – to benefit from it.

At the heart of this kind of love is an effort to see beyond the outwardly unappealing surface of another human – in search of the tender, interesting, scared and vulnerable person inside.

What we know as the ‘work’ of love is the emotional, imaginative labour that’s required to peer behind an off-putting facade. Our minds tend fiercely to resist such a move. They follow well worn grooves that feel at once familiar and justified. For instance: if someone has hurt us we naturally see them as horrible. The thought they might themselves be hurting inside feels very weird. If a person looks odd, we find it extremely difficult to recognise there might well be many touching things about them deep down.

If unpleasant events happen in someone’s life – if they keep on losing their job or acquire a habit of drinking too much or even develop cancer – we’re somehow tempted to hold them responsible for their misfortunes.

It takes quite a deliberate, taxing effort of the mind to move ourselves off these deeply established responses. To do so might mean taking an unappealing-looking person and trying to imagine them as young a child, unselfconsciously playing on their bedroom floor. We might try to picture their mother, not long after their birth, holding them in her arms, overcome by passionate love for this new little life. Or perhaps, drunk and passed out, ignoring their desperate cries.

We might see a furious person in a restaurant violently complaining that the tomato sauce is on the wrong place on their plate – but rather than condemn and feel superior, we might try to construct a story of how this individual had come to be so impossible, and how powerless they must feel in a world where something (and not what they are ostensibly complaining about) has frustrated them to the core.

The more energy we expend in thinking like this, the more we stand to discover a very surprising truth: that we could potentially see the loveable sides of pretty much anyone.

That doesn’t mean we should give up all criteria when searching for a partner. It’s a way of saying that the nicest person will eventually require us to look at them with imagination as we try to negotiate around some of their gravely dispiriting sides.

And, of course, the traffic won’t ever be all one way. We too are deeply challenging to be around and therefore stand in need of a constantly imaginative, tender gaze to rescue us from being dismissed as merely another everyday monster – or leper.