Work • Consumption & Need

Why We Continue to Love Expensive Things

Despite the widespread availability of good quality cheap products (watches, handbags, cars…), there remains a remarkable appetite for extremely expensive versions of them – which seems deeply weird at first sight. The so-called luxury sector appears to defy economic logic.

These two timepieces do very much the same thing. Both can tell you barometric pressure at 1,000 feet below the surface of the sea; both will be able to time a 100 meter race down to split second accuracy; both can accommodate leap years with ease; and both are elegantly styled in sensuous steel alloys. But a key difference is that one costs £100, and the other £20,000.

So the immediate question is: why would someone spend two hundred times more on a watch? The standard response at this point is to get rather severe, judgmental and censorious; and to assume that the only reason one might buy the expensive item is the desire to show off, to parade one’s affluence and to try to humiliate others. In short, buying it is a piece of aggressive self-assertion. This sort of analysis derives from our society’s folk memory of a stock character in fiction – the mean rich idiot – whom we know from Rabelais and Dickens, Thackeray and Amis. The names may keep changing but the character is the same.

Nick Frost as John Self in a 2010 BBC adaptation of Amis’s Money.

And yet the key to human progress isn’t how energetically we denounce things, but how perceptively we come to understand the inner workings of troubling behaviour (whether it be shoplifting, bulimia or buying a Rolex). As we have arduously managed to get better accounts of the origins of crime (and therefore come to deal with it more adroitly), a similar move awaits in the area of luxury goods. We’re facing a pathology which needs to be treated with kindness and insight.

This issue needs to be addressed urgently because it’s remarkably stressful to live in a society where luxury seems like a necessary route to a good life. The implicit philosophy of luxury goods is that the ingredients of fulfilment lie considerably outside an ordinary salary; which condemns a huge section of society to feelings of incompleteness. By definition ‘luxury’ is what 95% of the population either cannot, or can only just (with huge effort) afford. So there’s a genuine need to attack the brilliance with which luxury has managed to position itself as both central to life – yet unavailable. Luxury has a menacing, baffling position in relation to our ambitions.

But we can suggest that the impulse to buy luxury goods doesn’t come from greed or the desire to humiliate others. It springs from two motives. The first is fear; fear of most other people. The love of luxury breeds in societies where it feels very dangerous to be average, like 18th-century France or contemporary India or China. It isn’t coincidental that the love of luxury has been particularly in evidence in societies where the average existence is a properly painful place to be. It may be easy for us to dismiss as ‘superfluous’ the layers of gold, the cherubs, the diamonds and sculpted reliefs; but these can seem like very necessary tokens of separation between the owner and a genuinely squalid world beyond. They are forms of protection against the terror of an average life, in societies where average means appalling.

The taste for luxury isn’t just defined by the trajectory of nations, it is also defined by a person’s place within a society. It shouldn’t surprise us that a taste relatively close to that found at Versailles should also thrive in some south London housing estates. The motives are the same: it is a desire to show that one is ‘different’, when being the same means to be very short of dignity and respect.

It also shouldn’t surprise us that certain places are rather inimical to luxury, that Rolex and Louis Vuitton, Prada and Aston Martin have done spectacularly badly in Denmark, a country which boasts the third highest level per capita income in the world and one of the most equal distributions of wealth anywhere.

The Danish case illustrates one large possible solution to the social problem of luxury. The desire for luxury is inversely related to the level of dignity of an average life; as dignity goes up, so the desire for luxury comes down. It was never really about greed, the love of luxury was an individual response to a political failure: the inability of governments to ensure that an average life could be a flourishing life.

© Flickr/seier+seier

But politics may take a very long time to solve this issue and while we wait, there’s another major move to undercut the debilitating need for luxury. Politics wants to change ordinary life; but another strategy is to re-evaluate ordinary life, to see the hidden worth beneath apparently unimpressive things and people. This is the move that has, traditionally, been made by certain religions, Christianity and Buddhism in particular. Both these disciplines upgrade the average, they insist that very important things are going on in humble vessels. They deny that outward show is the sign of value.

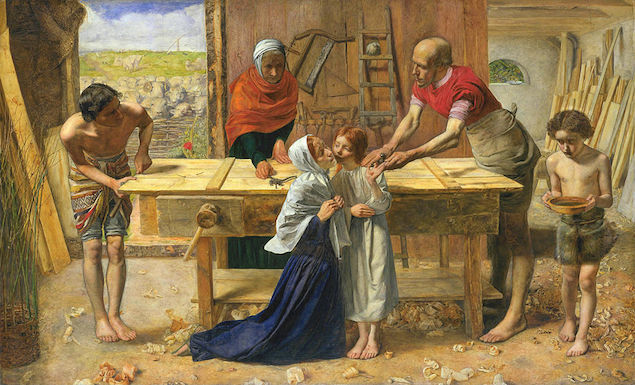

In John Everett Millais’s 1850 painting – Christ in the House of his Parents – the central, most esteemed figure of Christianity, Jesus himself, is shown in his everyday surroundings. It is emphatically an ‘ordinary’ place that the King of Kings inhabits.

Millais has carefully portrayed the messy earthen floor, the bare walls, the homespun clothes, the lack of shoes; the absence of any of the period equivalent of luxury brands. But at the same time he’s asking us to see this unglamorous scene as hugely important. The most esteemed things in the world are going on here – only without much external show. It’s a message Christianity was trying to teach in many ways: the ordinary isn’t really ordinary.

You don’t have to be officially religious, or even that sympathetic to many of the tenets of the faiths, to see the worth of this move. It’s one that has developed an independent life; we see it in the visual arts without any superstitious underpinnings, for example, in the work of the Danish painter, Christen Kobke, who stokes our enthusiasm for unpretentious calm evenings by the lake shore.

That we should be drawn to luxury isn’t just a fear of the average, it’s also a symptom of trust in authority, driven to a potentially excessive degree. Trust in authority is frequently a very good thing. It’s what gets us through school, allows us to drive cars safely in busy cities, means we will queue willingly at airports and follow the instructions of a fire officer.

Applied to culture, trust in authority has been useful in directing us to some great works: it is what advised us to pay attention to the paintings of Rothko and the novels W.G. Sebald (neither of which we might, left to ourselves, have encountered or persisted with).

Trust in cultural authority got us to be notice this.

But this trust can be usurped by the less deserving characters from ad agencies, who act a little like a malevolent supply teacher who work on a student’s credulity, exploiting his trust in authority, built up over years by a series of benign teachers. Our willingness to do what we’re assured is the right thing gets us into trouble when it’s hijacked by people who don’t really have our best interests at heart.

Our love of luxury goods isn’t freakish or vainglorious. It is attuned to some genuine needs: the need not to be drawn into a degraded average existence and to follow the prestigious voices of authority, speaking to us from billboards and magazines. These goods will continue to hold a central place until we find better solutions to the problems in our natures and in our societies that they so adroitly feed upon.